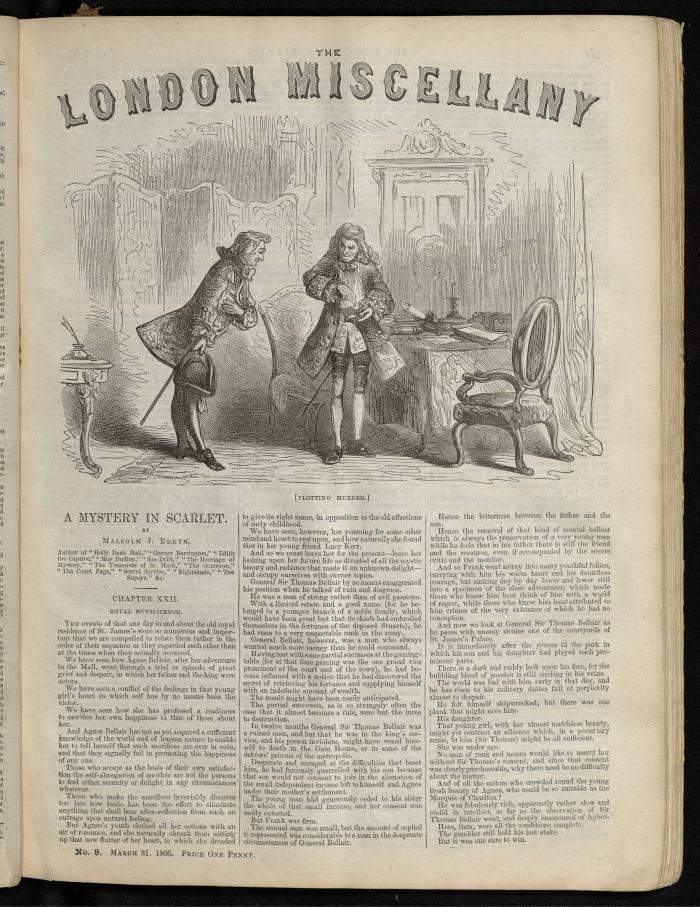

A MYSTERY IN SCARLET.

by

Malcolm J. Errym,

Author of "Holly Bush Hall," "George Barrington," "Edith the Captive," "May Dudley," “Sea-Drift," "The Marriage of Mystery," "The Treasures of St. Mark," "The Octoroon," "The Court Page," "Secret Service," "Nightshade," "The Sepoys," &c.

CHAPTER XXII.

ROYAL MUNIFICENCE.

The events of that one day in about the old royal residence of St. James's wore so numerous and important that we are compelled to relate them rather in the order of their sequence as they regarded each other than at the times when they actually occurred.

We have seen how Agnes Bellair, after her adventure in the Mall, went through a trial or episode of great grief and despair, in which her father and the king were actors.

We have seen a conflict of the feelings in that young girl's heart in which self has by no means been the victor.

We have seen how she has professed a readiness to sacrifice her own happiness to that of those about her.

And Agnes Bellair has not as yet acquired a sufficient knowledge of the world and of human nature to enable her to tell herself that such sacrifices are ever in vain, and that they signally fail in promoting the happiness of any one.

Those who accept as the basis of their own satisfaction the self-abnegation of another are not the persons to find either serenity or delight in any circumstances whatever.

Those who make the sacrifices invariably discover too late how futile has been the effort to eliminate anything that shall bear after-reflection from such on outrage upon natural feeling.

But Agnes's youth clothed all her actions with an air of romance, and she naturally shrank from setting up that new flutter of her heart, to which she dreaded to give its right name, in opposition to the old affections of early childhood.

We have seen, however, her yearning for some other mind and heart to rest upon, and how naturally she found that in her young friend Lucy Kerr.

And so we must leave her for the present—leave her looking upon her future life as divested of all the mystic beauty and radiance that made it an unknown delight—and occupy ourselves with sterner topics.

General Sir Thomas Bellair by no means exaggerated his position when he talked of ruin and disgrace.

He was a man of strong rather than of evil passions.

With a limited estate and a good name (for he belonged to a younger branch of a noble family, which would have been great but that its chiefs had embroiled themselves in the fortunes of the deposed Stuarts), he had risen to a very respectable rank in the army.

General Bellair, however, was a man who always wanted much more money than he could command.

Having met with some partial successes at the gaming-table (for at that time gaming was the one grand vice prominent at the court end of the town), he had become inflamed with a notion that he had discovered the secret of retrieving his fortunes and supplying himself with an indefinite amount of wealth.

The result might have been easily anticipated. The partial successes, as is so strangely often the case that it almost becomes a rule, were but the lures to destruction.

In twelve months, General Sir Thomas Bellair was a ruined man, and but that he was in the king's service, and his person inviolate, might have vexed himself to death in the Gate House, or in some of the debtors' prisons of the metropolis.

Desperate and enraged at the difficulties that beset him, he had furiously quarrelled with his son because that son would not consent to join in the alienation of the small independent income left to himself and Agnes under their mother's settlement.

The young man had generously ceded to his sister the whole of that small income, and her consent was easily extorted.

But Frank was firm. The annual sum was small, but the amount of capital it represented was considerable to a man in the desperate circumstances of General Bellair.

Hence the bitterness between the father and the son.

Hence the removal of that kind of menial ballast which is always the preservation of a very young man while he feels that in his father there is still the friend and the resource, even if accompanied by the severe critic and the monitor.

And so Frank went astray into many youthful follies, carrying with him his warm heart and his dauntless courage, but sinking day by day lower and lower still into a specimen of the class adventurer, which made those who knew him best think of him with a world of regret, while those who knew him least attributed to him crimes of the very existence of which he had no conception.

And now we look at General Sir Thomas Bellair as he paces with uneasy strides one of the courtyards of St. James's Palace.

It is immediately after the fracas in the park in which his son and his daughter had played such prominent parts.

There is a dark and ruddy look upon his face, for the bubbling blood of passion is still circling in his veins.

The world was bad with him early in that day, and he has risen to his military duties full of perplexity almost to despair. He felt himself shipwrecked; but there was one plank that might save him.

His daughter. That young girl, with her almost matchless beauty, might yet contract an alliance which, in a pecuniary sense, to him (Sir Thomas) might be all sufficient.

She was under age. No man of rank and means would like to marry her without Sir Thomas's consent, and since that consent was clearly purchaseable, why there need be no difficulty about the matter.

And of all the suitors who crowded round the young fresh beauty of Agnes, who could be so suitable as the Marquis of Charlton?

He was fabulously rich, apparently rather slow and stolid in intellect, as far as the observation of Sir Thomas Bellair went, and deeply enamoured of Agnes.

Here, then, were all the conditions complete. The gambler still held his last stake.

But it was one sure to win.

p. 114

No wonder, then, that the episode in the park, in which son and daughter and projected son-in-law all seemed in arms against him, struck General Bellair to the very soul and filled him with despair.

"All is lost now," he muttered to himself, as he impatiently motioned to the sentinel on duty to continue his march and take no further notice of him, for the soldier had drawn himself up to rigid "attention."

"All is lost now. Charlton may declare off, seeing what his brother-in-law is and is likely to become. The momentary admiration for a girl who achieves the escape of a highwayman by the force of her pretty face and sparkling eyes will die away before the terrors of an alliance with such a family as we have shown ourselves to be. Fool, fool, that I was, not to allow the rascal to parade his insolence quietly, and then go his way! What is to be done now? I have placed Charlton in arrest, too. More folly! more folly! But I was enraged, I am enraged still. What is to be done? Confusion seize them all! He may love her still, and doubtless does, for a passion of the eyes little heeds the reasoning of the brain. He may love her, but will he marry her—the sister of a highwayman, the daughter of a bankrupt ruined soldier? Never! never! never!"

"General."

"And my own folly too—at least, half of it my own folly. I should have temporised and smiled, and, per chance, shed a tear or two; but I am not made of that kind of stuff. Curses on them all!"

"General."

"Who are you? What is it? Oh! Mr. Norris."

"My dear general, his most gracious Majesty, our royal master, receiving your message by Mr. Hartley, the page on duty, graciously accords the desired interview."

"What? What is it?"

"My dear general, you are strangely disturbed. He! he! he! If you bring so preoccupied a mind to the little board of green cloth upstairs above the Tennis Court you will scarcely have a chance against — against—"

"Against you, Mr. Norris. I recollect. You have won largely at that same little board of green cloth, and I, like a rash fool—"

"General! general!—he! he! he!—don't be too candid, and allow me to add that his most gracious Majesty is apt to be impatient, and may actually be nearly waiting in the royal cabinet for your dutiful report."

"Report? report? What is it? What? What? Oh! I suppose I am going mad. To be sure, I have a report to make to the king himself, according to standing orders that such a course should be taken invariably when any officer of the Guard is ordered under arrest. It is a privilege of the household troops that the monarch himself should be referred to in such cases. I had forgotten—I had forgotten."

"He! he! he!"

"Silence, Mr. Norris! Your insane laughter—if by a stretch of compliment I can call it such—is annoying and vexatious. I will see the king."

"Gracious goodness, general! The world's at an end. You will see the king! you will see him! Gracious goodness! What language to use towards his Majesty, who, with a condescension of the most wonderful character—"

"Silence, Mr. Norris, and lead the way. I am in no mood for trifling, whatever you may be."

Norris held up his hands as though his astonishment were too great for words, and preceding General Bellair across the Colour Court, he rapped in a peculiar manner at one of the doors opening on to the quadrangle. The door was opened a short distance.

"Who knocks?" asked a yeoman of the Guard, who stood immediately within, and who hung his halbert slantingly across the opening.

"King's service," replied Norris. "Pass, on king's service."

This seemed to be in regular form, by the careless manner in which it was gone through, for the king's valet knew the yeoman of the Guard, and the yeoman of the Guard knew him perfectly well.

Immediately within the door was a small square space not much larger than the hall of an ordinary London mansion.

At the further extremity of this were some five or six stairs, terminating abruptly by a heavy-looking door covered with crimson cloth and studded profusely with gilt nails.

Closely followed by General Bellair, Norris the valet ascended these few steps and rapped at the door in the same way that he had done at that which led directly from the Colour Court.

That door was then opened a short distance and the cold glitter of a slender court sword gleamed across the opening. The same form then ensued of question and answer.

"Who knocks?"

"King's service."

"Pass, on king's service."

The continuation of the staircase went right up to the first floor of the palace, and the stairs themselves were covered with very dark crimson cloth, showing no inconsiderable amount of wear at the edges.

The top of the stairs terminated in a corridor about twelve feet in length, at the end of which was a small room, the walls of which were ornamented with ancient arms grouped in many curious devices.

Norris paused not a moment, however, in his progress, but conducted the general right through this littler armoury into a rather handsome apartment richly furnished, the windows, and indeed most of the walls, being hung with costly maroon coloured velvet.

The principal peculiarity of this apartment was that at its further extremity there were three raised steps of a semicircular form, and in the centre of the upper most one, forming a good portion of its diameter, was a door very richly gilt, and panelled with looking glass.

That door led directly to the royal cabinet.

And when it became necessary for "his gracious Majesty," as Norris would say, to receive, in the course of his ordinary regal duty, reports, deputations, or remonstrances, the gilt door would be flung open, and the royalty of England would appear for a few moments on its threshold.

This arrangement gave his gracious Majesty a kind of advantage over every one in the room below, and the opportunity of effecting an immediate and abrupt retreat in case of anything unpleasant occurring.

General Bellair understood all this very well.

Being in command of the troops in the London district, he had had several times occasion to make reports to the king.

He now therefore stood facing the gilt door, but not at all intruding upon the circular steps, waiting some what moodily for the mere ordinary routine ceremony that was about to take place.

But Norris crawled up the steps and rapped at 1he lowest portion of the door as though within it were enshrined some idol it was the special business of his life to worship.

There was no response to his rap at the door, and he waited about three minutes.

Tap, tap, again.

There was some noise from within—a noise perfectly unintelligible; but Norris it appeared understood it, for he slid down the steps until he came to the first one, upon which he sat with an appearance of great humility.

General Bellair drew himself up to his full height, and, hastily dragging his sword from its scabbard, he assumed the attitude of a military salute.

The gilt door Hashed open, and the mirrors which were let into its panels seemed as though they whirled the room round and round by the variety of images that rushed over their surfaces.

The king stood on the topmost step, with that glittering diamond-bedecked snuff-box in his hand, which was always to be found either elevated towards the royal nose or in the depths of one of the huge flapped waistcoat pockets.

There was an urbane, and we may almost say pleasant look, by general contrast, on the royal countenance.

The gracious fingers rapped gently upon the lid of the jewelled snuff-box.

Certainly the facial contortion of his gracious Majesty meant a smile.

"Ha! ha! Our good General Bellair. Ugh! ugh! ugh!"

CHAPTER XXIII.

TEMPTATION.

General Bellair somewhat controlled himself to speak quietly and benignly in the presence of royalty.

"I have the honour to report to your Majesty—"

"Tash! tash!"

"Your Majesty?"

"Tash! tash! Our good General Bellair—our excellent friend and good subject General Bellair. Tash! tash!"

The general looked amazed.

The king descended one of the steps.

"Tash! tash! It gives us great pleasure, singular pleasure, to see our good friend General Bellair."

Norris looked up from his crouching attitude upon the lowest step, and the king, being immediately above him, took at once the opportunity of dropping the heavy gold and jewelled snuff-box upon his head.

"Our excellent friend General Bellair, we are always well pleased—always well pleased—"

"Your Majesty, I have the honour to report—"

"Tash! tash! man! Tash! We are quite at leisure. Quite."

The king descended the last step, making use of Norris's back as if in mistake for a portion of it as he did so.

Taking hold then of General Bellair by the cuff of his coat with the royal finger and thumb, he led him towards the steps.

"Hither, hither, our good General Bellair. Ugh! ugh! ugh! In truth we should have sent for you. Hither with us to our cabinet."

Norris was all amazement. He knelt on the steps and held up the snuff-box on his two hands, something after the manner of a mayor of a corporate city offering its keys during a royal progress.

The king kept hold of the cuff of General Bellair with the finger and thumb of his right hand; with the left he took the snuff-box from Norris, and with the sharp edge of it, corrugated and dangerous with its diamonds, he made use of the valet's head as a sort of balustrade to lean upon, dealing him two such hard raps that, after the gilt and mirror-panelled door was closed upon the king and the general, Norris took off his wig and rubbed his head, with tears in his eyes.

"Your Majesty is too gracious."

"No. Ugh! ugh! ugh! No. A faithful soldier of the king is always—always the king's friend."

His Majesty pushed open the lid of the snuff-box, and handed it to the general.

"Keep it, keep it, our good General Bellair. A souvenir from the king. Keep it."

"Oh! your Majesty—" "Ugh! ugh! ugh! That is to say, we will give it you when we get another. Ugh! ugh! ugh!"

The snuff-box closed with a snap, and was plunged at once into the depths of one of the waistcoat pockets.

The king then subsided into a chair, and crossed his thin legs one over the other, while the general stood respectfully some few paces distant.

"And so, our good General Bellair, you have some thing to report to us?"

"With your Majesty's good fayour I have. There was a kind of, I may almost call it brawl, in the Mall to-day, and I have been under the painful necessity of placing Lieutenant-Colonel the Marquis of Charlton under arrest."

"Ugh! ugh! ugh! Tash!"

It was rather difficult to gather the royal opinion from these expressions, and the general waited for something more explicit.

The snuff-box was produced again, and the king took a huge pinch.

"In old times, our dear General Bellair, we believe that brawling within the precincts of the palace was the loss of a hand. Ugh! There are no amusements now. The hand was chopped off at the wrist, and the stump seared in boiling pitch. Ugh! The humorous spirit of the age has passed away. Ugh! General Bellair, our good General Bellair—ugh! —you see we take a pinch out of your box. We don't forget our good General Bellair. This young Marquis of Charlton is Lieutenant-Colonel of the Guard, now on duty at our palace, here, of St. James's. Ugh!"

"It is so, your Majesty. Lieutenant Ogilvie, a young subaltern, who has the night watch at the gate, is in possession of his sword, and, if your Majesty pleases, will detail the circumstances that—"

"Tash!"

"Your Majesty?"

"Tash! We don't want to hear. All brave men, all gallant men. Ogilvie, a young subaltern looking for promotion. Ugh! the Marquis of Charlton, under arrest, and looking for penalties, ugh! Has our dear General Bellair any favour to ask of us? Ugh! ugh! ugh!"

"Favour, your Majesty?"

"Yes, any favour that will endear him further to the king, and draw him closer still to the king's service. You see we take another pinch out of your box, general. Ugh! ugh! ugh!"

"Oh! your Majesty, if indeed my past services have found favour in your Majesty's eyes, and if I dare venture to hope that some royal grant might retrieve the fallen fortunes of a soldier—"

"Tash! tash! We have a barony, and who can we bestow it on better than our dear friend General Bellair? Baron Bellair, of—of Stillingfleet."

"Your Majesty?"

"That is the name of the royal domain—a crown grant, with which we will accompany the title."

The general bent his knee.

"Oh! your Majesty, how have I merited at your gracious hands this goodness, this generosity, this —"

"Not at all, man, not at all; but you will."

General Bellair understood his condition in a moment.

He was to do something, and the barony and the estate at Stillingfleet were the price. He turned deathly pale.

"Our good general, you see we take another pinch out of your box. We shall always call it our good General Bellair's box, which he lends to the king. Ugh! ugh! Lends to the king. And now, our good friend, you will release Lieutenant-Colonel the Marquis of Charlton, and at the same time you will commend the young subaltern Ogilvie for his good service, and—and this evening (it may be this evening, between seven and eight).—this evening, our dear Bellair, it may be that we, we ourselves, we the king, may think fit to order a court-martial for an outrage against our royal person on the part of one of our officers—a court-martial which shall take evidence promptly and quickly, and which cannot come to any other conclusion than one. You see, our dear general, we take another pinch out of your box."

"A court-martial, your Majesty?"

"We have said it. Yourself the president, and Lieutenant-Colonel the Marquis of Charlton and the subaltern Ogilvie the members."

Sir Thomas Bellair drew a long breath.

"May I inquire the officer's name, your Majesty?"

"Tash!"

"May I then inquire his offence?"

"Tash!" The general bowed low.

p. 115

"Our dear general, there is a third inquiry which you may make."

"A third inquiry, your Majesty?"

"Yes. The sentence."

"The sentence?"

"Yes; the sentence will be—will be—ugh! ugh! ugh!—the sentence will be that the prisoner—We are taking a quantity of snuff from your box, our dear general."

"Yes, your Majesty, you were graciously pleased to say that the sentence would be that the prisoner—"

"Yes, that the prisoner should be—"

Tap, tap, tap went the royal fingers on the lid of the snuff-box.

"That the prisoner should be—" almost gasped General Bellair, for he seemed to see and hear in the air about him the word that was to come.

"Shot!" said the king.

General Bellair knew perfectly well that that was the sentence. It was as plain to him as possible.

There was no longer any mystery in the affair.

The king had an enemy, and that enemy, being an officer, was amenable to military law, under the pains and penalties of which he was to be brought rightfully or wrongfully, and then shot. It was to be a judicial murder.

A hideous farce, ended by a hideous tragedy.

And in that manner was Sir Thomas Bellair to earn his barony and his estate.

He was a strong, brave, although a bad man, and now he set his teeth hard and breathed with difficulty, for he was trying to reconcile himself to what he had to do. It did not exactly occur to him to start to his feet and cry out, "No; were you ten times a king I will not blacken and smirch my soul by committing murder for your sake."

No such idea ever presented itself to General Bellair, and whatever might have been his ordinary amount of conscientiousness, it was now completely submerged in the difficulties of his position.

The confidence of such a king as George the Second was a kind of moral quagmire or tenacious ditch, into which having once been flung or having waded there was no safe retreat.

The circumstances of General Bellair were nearly desperate before this interview with his gracious monarch and master; but much more desperate would they be were he to refuse the service sought of him!

No, there was no resource.

He stood upon a precipice before the interview.

To reject the king's overtures would be to be toppled over it.

He might be deprived of his command the next morning, superseded, dismissed the service, and flung helpless and defenceless into the hands of his worst foes, which General Bellair would have deemed to be his creditors.

The king watched the mental struggle through his half-closed eyes, and turned yellower and yellower and more cadaverous as he did so.

Then General Bellair drew a long breath, and struck himself on the breast.

"I will do it," he said. "Of course. Ugh! ugh! ugh!"

"But—"

"But what?"

"The Marquis of Charlton will shrink—"

"Ah!"

"He will shrink aghast. He—he wants no barony—he wants no estate.”

"Tash! All men want something. What shall we give him?"

The general shook his head.

"Think again, our good Bellair, while we take another pinch out of your box. Think again. What does the Marquis of Charlton want? As for the young man Ogilvie, he wants his captaincy, of course. Ugh! you can promise it to him, good Bellair. But what shall we give the Marquis of Charlton? The next vacant garter, and in the meantime our Hanoverian order? Ugh! Or—or what?"

General Bellair clapped his hands together suddenly.

The king gave a start and held out the snuff-box in an attitude of defence.

"I have it, your Majesty. I know what the Marquis of Charlton wants."

"What?"

"My daughter."

"Let him have her, by all means."

"But I fear, your Majesty, I fear—"

"What?"

"I fear she does not love him."

"Tash! Our good Bellair, are you a man of the world, and talk such—such trash to us? Let him have her. She will learn to love him in good time. Let him have her."

"I have a thought, your Majesty. My daughter Agnes has—has strong domestic affections."

The general gulped down a spasm of emotion.

"She—she is fondly attached to her brother, between whom and myself there are unhappy differences, and I almost fear he has made himself amenable to your Majesty's laws, and, moreover and notwithstanding that —that—well, well, I believe she loves me still."

"We see, we see. We congratulate you, general, and we do you the honour of taking another pinch from your box. You will represent to the young lady that our pardon of her brother, let his offences be what they may, and your preservation from ruin will be the price of her consent to an union with the Marquis of Charlton."

"That might succeed, and then if I could go to the marquis with her consent on my lips, 1 might move him to your Majesty's wishes."

"Ugh! Our dear Bellair, you, and we, and all thinking people know that every man and every woman have their price, if we can only find out what it is. Ugh! Send for the young lady here. We will retire to the further apartment, and we will hear her resolution."

"Should she refuse?"

"Tash! man! tash!

"She will not refuse."

The king hastily left the small cabinet by another door, which the general had not previously observed, and the result of the interview with Agnes when sent for by her father the reader is already aware of.

CHAPTER XXIV.

UNDER ARREST.

The officers' guard-room in St. James's Palace was on the ground floor, to the left of the great gate way.

You went through a long dreary apartment, which was the common room of the privates and non-commissioned officers, and before the blazing fireplace of which the soldiers on duty for the next relief of the sentinels at the various posts about the royal building lounged and chatted.

Their muskets occupied racks ranged against the walls, and the whole place presented a litter of military accoutrements.

The floors of the old palace of St. James's are on so many different levels that short flights of three, four, or five stairs frequently lead from one room to an other.

In one corner, then, of this common guard-chamber there was such a flight of stairs, and at their summit a massive door conducting to a short passage, on each side of which were several apartments.

The first to the left led into the officers' guard- chamber, a handsome enough room, and well appointed, with three windows looking up St. James's Street.

The rooms to the right had windows looking into the Colour Court, and were seldom used, but it was in one of these that the Marquis of Charlton was a prisoner, not exactly on parole, but upon honour, for the door was not fastened upon him, and the sentinel who paraded the passage without would certainly not have obstructed him had he attempted to pass his post.

The marquis was pacing to and fro, evidently disturbed in mind.

"All my love and devotion," he cried, "are castaway upon her. I suppose I am not courtier enough to please her. I never can manage to turn a compliment at the proper moment, like these Walpoles and Boltons and other flutterers of the court, and all I can manage to say to her is, 'Agnes Bellair, I love you very much, and would gladly make you Marchioness of Charlton.' But that does not seem to do. She fences with me, laughs at me, avoids me. Alas! And she is so beautiful! I can never love another—never! never! And here is this arrest, too; but what does it matter? If I were as free as air she would not see me, for I can never even get speech with her except in some public place in the midst of a crowd, and then she flouts at me and brings the laugh upon me, just because I am a trifle heavy-witted. Foolish girl! Yes, oh! yes, she is a foolish girl, for let her beauty last to its latest span she will never get one to love her more truly, more sincerely than I do. A dream! a dream! it is but a dream. Awaken from it, Charlton! awaken! Let her go, man; let her go. Let me study the old couplet, which will be for ever fresh in wisdom—

What care I how fair she is,

If her smiles are not for me?"

"My lord."

The marquis turned hastily, and saw standing on the threshold of the apartment General Bellair; how old he looked!

The strong stalwart man seemed as though since that interview with the king the ravages of ten years had swept across his frame.

There was a something still in the heart of the ruined gamester—a something still in the soul of the brave soldier which revolted against the unholy compact he had entered into.

"General."

"Marquis, by order of the king, you are free from arrest."

"A thousand thanks."

"And—and, marquis, I bring you, for the first time, without doubt, fear, or equivocation, the consent of my daughter Agnes to become Marchioness of Charlton."

The young man paled for a moment, and then a flush of colour visited his cheeks. He held out both his hands to the general.

"Welcome, oh! most welcome words. I love her. Sir Thomas, better than my life. Why this is indeed the dark cloud with the silver lining. General, if the devotion, the ardent affection, the—the—but I will not protest. Time alone can show that with all my heart and soul I love her, and that I will he to her—well, well, I cannot speak—my words come confusedly. Bear with me, general, for a moment. Yes, these are tears, but the heart will overflow from gladness as often as from grief."

"No more," said Bellair, and he carefully avoided looking into the eyes of the young marquis.

"No more, Charlton. I am quite sure that you will be to her all that I could wish. I have had an interview with the king, and, although I may say, of course, that we do not live in despotic times, and, therefore, that we may marry and rejoice without the will of the monarch, I may say that his Majesty is so well pleased that he has offered me a barony, so that the social state of Agnes reaches somewhat higher towards your own, marquis."

"I rejoice to hear it."

"I thank you much, I thank you much. How quickly the day droops! Shadows are already gathering in the Colour Court."

"There are no shadows henceforth for me, for all is brightness and sunshine."

"Yes, yes, By the bye, I rather think we shall have a disagreeable duty to-night." "Indeed? Will it rain?"

"No, no; it is not that. But I hear something of a court-martial on foot, and—and the king looks specially to its members, its principal members, who will be you and myself, for strict justice."

"Of course, of course."

"Oh! yes, as you say, of course, of course, and it strikes me that—that in some way his Majesty, or perhaps the queen—ah! to be sure, it was most probably the queen—has induced Agnes to give her consent to your wishes on the sort of—sort of understanding that the sentence of the court-martial will be in accordance with his Majesty's desires."

The Marquis of Charlton was silent for a few moments, and then he spoke in a saddened tone.

"General, if Agnes has given her consent to an union with me from any other feeling than that she will be happy with—"

"No, no, hastily interrupted the general. "I meant merely as regarded the time of your marriage. You see she is still but young, and, girl-like, she is playing and fluttering with her liberty. Oh! believe me, Marquis, it was merely a question of time."

"Then in that case—"

"Exactly. We can conform to his Majesty's wishes. Do not leave the palace until you hear from me again. Of course you understand your arrest is over. I shall order Mr. Ogilvie to deliver you your sword again. Of course we can easily fulfil his Majesty's wishes."

"Oh! of course."

"Exactly so. I promised for myself, and I promised for you."

"You were quite right, general. Whatever is correct and just—"

"Exactly, exactly. And now that we understand each other, Charlton, I am able with all my heart to wish you joy. How dark it is getting! You must have lights. Lights! Lights here, for Colonel the Marquis of Charlton! Lights, I say!"

The general clattered down the stops and passed through the common guard-room with hasty strides.

"What does he mean?" asked the marquis of himself when he was once more alone.

"What is the meaning of it all? I never saw Bellair so shaken in my life I cannot comprehend him. Put down the lights, Dick Martin."

"Yes, colonel."

A drummer of the guard had brought in two candles in silver candlesticks, and stood all "attention" for further orders.

"Is Mr. Ogilvie below?"

"No, colonel," cried Lieutenant Ogilvie, as he stepped across the threshold of the room at that moment.

"No, colonel. I am here, and I have the honour and gratification, all in one, of presenting you with your sword."

"Thank you, Ogilvie, thank you. I know you took it with regret."

"I did indeed, colonel."

"Well, there is no mistaking, Ogilvie, that you return it with pleasure, for you are quite radiant with smiles."

"There is another reason for that, marquis."

"Indeed? Is it asking too much to—to—"

"Not at all. I am sure you will be pleased, colonel. General Bellair has just now, in the name of the king, promised me the first vacant company."

"Oh!"

"I am sure you are pleased, colonel."

"Ogilvie, for your sake I am of course pleased but I cannot understand it."

"Why, it is as plain as Sergeant Moore's pikestaff."

"Not quite. Be off with you, Dick Martin, and shut the door after you. I repeat I do not understand it, Ogilvie."

"But what? What?"

"Stop a bit. Do you think General Sir Thomas Bellair looks very like a benevolent fairy? and do you think” (speaking in a lower tone still) “that his most gracious Majesty George the Second of this realm is exactly boiling over with benevolence?"

p. 116

"No, no."

"Precisely. Don't speak so loud. You have answered both my questions with a 'no' to each. Ogilvie, there is something brewing. I don't know what it is, but the king is distributing favours right and left—baronies, estates, wives, captaincies."

"No!"

"It is so, my good Ogilvie, it is so."

"Well, but—

"Hush! Hush! Hush! It is said that walls have ears, and if any walls have particularly long ones, they are certainly the walls of palaces. Get your cloak and come into the garden. We must have a chat over this."

"A lady, colonel."

"A what?"

"A lady—no name—a mask—roquelaire cloak—won't be said no to—waiting in guard-room below."

"For me, Dick Martin?"

"Yes, colonel."

"I discreetly retire," said Ogilvie, with a bow.

"No, no, not at all."

"Excuse me. Two are such good company, while three, you know—"

"Ogilvie, I do not like these jokes. My whole affections, my whole heart and soul are bound to one, and one only. But still there can be no reason why a lady upon proper grounds should not call upon a gentleman."

"Certainly not, colonel. Pray pardon me. I am afraid I have picked up the vice of the age, which is too often to talk lightly of what I know nothing about. Still, however, I will retire, and wait for you in the garden, for, after all, the lady's visit is for you, and not for me."

"Very well, Ogilvie, I will join you soon."

"Au revoir."

"Yet one moment, Ogilvie, one moment. Come to the window here."

Yes, marquis."

"Has anything been said to you about a court-martial?"

"Well—a—well—a—"

"Ah! I see it has. Tell me now, Ogilvie, as you are an honest fellow, what it was."

"The general said that he believed somewhere between seven and eight this evening a court-martial would be hastily summoned in the king's Armoury to try an officer for a serious military offence."

"Yes, yes. What more?"

"He said it would be composed of himself as the president, and probably of you and of me as members."

“What more?"

"He was a little positive and needlessly particular in enforcing upon me the necessity of not shrinking from doing my duty and passing such a sentence as the case might require."

"Ah!"

"You look disturbed, marquis. I hope there is nothing in all this that will be unbecoming to us as officers and gentlemen. Of course to become members of a court-martial, however disagreeable the duty may be, is still a duty."

"Ogilvie, Ogilvie, we are encompassed by some snare—some net with gilded meshes cast about us. We do not see our way just at present, but we shall."

"But what can it be?"

"Your captaincy—the consent of Lady Agnes Bellair to become my wife—and that puzzles me most of all, for if ever there was a piece of purity and nobleness in all this world, it is Sir Thomas Bellair's daughter. Oh! no, no, it is impossible. She ranks among the deceived, and not the deceivers, and Bellair himself is to have a barony, and Heaven knows what estates to back it."

"You frighten me, marquis. I am a young man—we are both young men, for the matter of that—but I have the pride and the honour of a soldier. If ready servile tools were wanted to carry out some base unworthy purpose, why, marquis, the mistake is fatal, since they have chosen you and me."

"Right, Ogilvie, right. Why should I feel sick at heart? Bellair may say and do what he pleases, but that does not coerce us, and not all the kings nor all the baronies—"

"Nor all the captaincies," exclaimed Ogilvie.

"Nor all the—oh! Ogilvie, I have a weight of depression here which, like the storm-cloud in the heavens, seems ominous of hurricane and devastation. Hush! we will say no more. Dick Martin!"

"Yes, colonel."

"Show the masked lady up, and see that the men below treat her with all respect. Go, Ogilvie, go. I will meet you in the garden shortly. We must talk more of this, for my heart is ill at case. Go, go."

(To be continued in our next.)