A MYSTERY IN SCARLET.

by

Malcolm J. Errym,

Author of "Holly Bush Hall," "George Barrington," "Edith the Captive," "May Dudley," “Sea-Drift," "The Marriage of Mystery," "The Treasures of St. Mark," "The Octoroon," "The Court Page," "Secret Service," "Nightshade," "The Sepoys," &c.

CHAPTER XLIII.

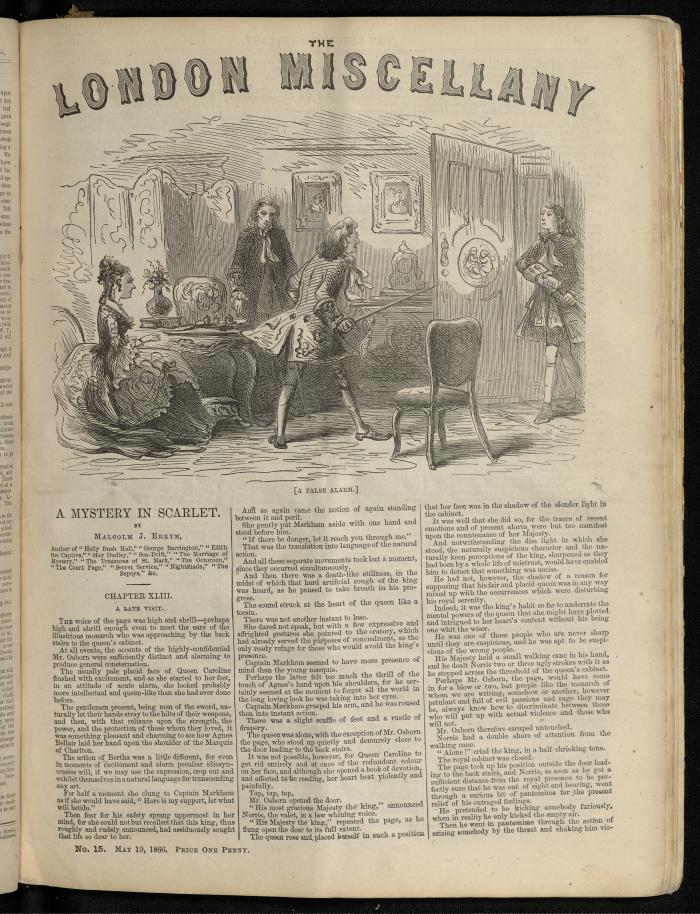

A LATE VISIT.

The voice of the page was high and shrill—perhaps high and shrill enough even to meet the ears of the illustrious monarch who was approaching by the back stairs to the queen's cabinet.

At all events, the accents of the highly-confidential Mr. Osborn were sufficiently distinct and alarming to produce general consternation.

The usually pale placid face of Queen Caroline flushed with excitement, and as she started to her feet, in an attitude of acute alarm, she looked probably more intellectual and queen-like than she had ever done before.

The gentlemen present, being men of the sword, naturally let their hands stray to the hilts of their weapons, and then, with that reliance upon the strength, the power, and the protection of those whom they loved, it was something pleasant and charming to see how Agnes Bellair laid her hand upon the shoulder of the Marquis of Charlton.

The action of Bertha was a little different, for even in moments of excitement and alarm peculiar idiosyncrasies will, if we may use the expression, crop out and exhibit themselves in a natural language far transcending any art.

For half a moment she clung to Captain Markham as if she would have said, "Here is my support, let what will betide.”

Then fear for his safety sprang uppermost in her mind, for she could not but recollect that this king, thus roughly and rudely announced, had assiduously sought that life so dear to her.

And so again came the notion of again standing between it and peril.

She gently put Markham aside with one hand and stood before him.

"If there be danger, let it reach you through me."

That was the translation into language of the natural action.

And all these separate movements took but a moment, since they occurred simultaneously.

And then there was a death-like stillness, in the midst of which that hard artificial cough of the king was heard, as he paused to take breath in his progress.

The sound struck at the heart of the queen like a tocsin.

There was not another instant to lose.

She dared not speak, but with a few expressive and affrighted gestures she pointed to the oratory, which had already served the purposes of concealment, as the only ready refuge for those who would avoid the king's presence.

Captain Markham seemed to have more presence of mind than the young marquis.

Perhaps the latter felt too much the thrill of the touch of Agnes' s hand upon his shoulders, for he certainly seemed at the moment to forget all the world in the long loving look he was taking into her eyes.

Captain Markham grasped his arm, and he was roused then into instant action.

There was a slight scuffle of feet and a rustle of drapery.

The queen was alone, with the exception of Mr. Osborn the page, who stood up quietly and demurely close to the door leading to the back stairs.

It was not possible, however, for Queen Caroline to get rid entirely and at once of the redundant colour on her face, and although she opened a book of devotion, and affected to be reading, her heart beat violently and painfully.

Tap, tap, tap[.]

Mr. Osborn opened the door. "His most gracious Majesty the king," announced Norris, the valet, in a low whining voice.

"His Majesty the king," repeated the page, as he flung open the door to its full extent.

The queen rose and placed herself in such a position that her face was in the shadow of the slender light in the cabinet.

It was well that she did so, for the traces of recent emotions and of present alarm were but too manifest upon the countenance of her Majesty.

And notwithstanding the dim light in which she stood, the naturally suspicious character and the naturally keen perceptions of the king, sharpened as they had been by a whole life of mistrust, would have enabled him to detect that something was amiss.

He had not, however, the shadow of a reason for supposing that his fair and placid queen was in any way mixed up with the occurrences which were disturbing his royal serenity.

Indeed, it was the king's habit so far to underrate the mental powers of the queen that she might have plotted and intrigued to her heart's content without his being one whit the wiser.

He was one of those people who are never sharp until they are suspicious, and he was apt to be suspicious of the wrong people.

His Majesty held a small walking cane in his hand, and he dealt Norris two or three ugly strokes with it as he stepped across the threshold of the queen's cabinet.

Perhaps Mr. Osborn, the page, would have come in for a blow or two, but people like the monarch of whom we are writing, somehow or another, however petulant and full of evil passions and rage they may be, always know how to discriminate between those who will put up with actual violence and those who will not.

Mr. Osborn therefore escaped untouched.

Norris had a double share of attention from the walking cane.

"Alone!" cried the king, in a half shrieking tone.

The royal cabinet was closed.

The page took up his position outside the door leading to the back stairs, and Norris, so soon as he got a sufficient distance from the royal presence to be perfectly sure that he was out of sight and hearing, went through a curious bit of pantomime for the[,] present relief of his outraged feelings.

He pretended to be kicking somebody furiously, when in reality he only kicked the empty air.

Then he went in pantomime through the action of seizing somebody by the throat and shaking him vio-

p. 226

lently to and fro, while he rained blows downward and sideways upon the devoted imaginary head.

"Take that!" said Norris, as he drew a long breath after his exertions. "Take that for the present, and something else and better will come soon."

Meantime the king had flung himself into the first easy chair he came to, and uttered three dismal groans.

"I fear,” said the queen, "your Majesty is indisposed.”

“You fear? you fear?” yelled the king. "Look at us and then answer yourself."

"Your Majesty?”

"We are worse than indisposed. We are murdered. It is regicide."

"What is the matter, sir?"

"The matter? the matter? Everything is the matter. Treason is the matter. Plots, plans, and assassinations are the matters."

"We grieve, sir—"

"Peace! Tash!"

The queen sat quietly down, and looked as placid as possible.

“We will go to Hanover," growled the king. "Tomorrow morning we will go to Hanover, and while we are gone, madam, we trust that the Duchess of Kendal will receive every attention at your hands."

There was the faintest possible tinge of colour in the face of the queen, but it passed away in a moment.

"Your Majesty's commands," she said, "have ever met with my most respectful attention."

"Bah! Bo!"

"And if that is all your Majesty has to say, as the hour is getting late—”

"We understand," growled the king. "You want to get, rid of us. Ha! ha! But we are not going so soon. Is it true, think you? Is there such a thing as woman's wit, and does it succeed sometimes in tracing events to causes when man's sterner judgment fails him utterly?"

This question was half put to the queen, and half as a kind of soliloquy, but she answered it.

"I shall only be too happy to be of any service to your Majesty."

“Ah!"

"And if you will only kindly inform me what it is that—that your Majesty wishes—"

"Ah!"

The queen was silent.

The king quietly laid the walking cane upon the nearest table, and then, peering suspiciously at the queen through his half-closed eyes, he spoke again.

"We will tell you, and it will be better than well if you can devise some mode by, which some most mysterious circumstances can be cleared up to our satisfaction."

The queen slightly inclined her head, as though to signify how willing, at all events, she was to try.

"Understand, then," added the king, in a croaking voice, "understand, then, that we have been surrounded by traitors, and that, with the assistance of Providence, we disposed of one at Kew, and of another in the court yard here of St. James's. Do you hear?”

“Certainly, sir."

"Well, well, well. Time was that when you killed a man there he lay, stiff, stark, solid, inert, and troublesome—a mass of carrion which you could neither feed your dogs with nor leave to rot—rot in the summer air. But now—now, madam, these dead men disappear, exhale, vanish into air, and no one can tell me whither they have gone."

"Indeed, sir?"

"Ah! indeed, madam. I want your woman's wit now."

"But, sir—"

"But me no buts. Where are my dead men? I must have them. I will have them."

"Your Majesty at once alarms and astonishes—"

"Tash!"

"Nay, sir."

"Tash! I say again. One thing suggests another. Listen. There was a sentinel, he held his post in the Colour Court of St. James's, and shortly after one of these arch-traitors had met his most deserved doom there came forth from one of the private doors of the palace three persons."

"Three persons?"

"We said three persons—three tall strong men."

"Oh! then, sir, they cannot concern me. I have none but the women of my chamber and the ladies of my court about me."

“Indeed! Now, what if that party of three consisted of two women and of one man? What if one of those three persons carried away one of my dead bodies?”

The alarm and apprehension of the queen were increasing each moment.

She was afraid to trust herself to speak.

She only shook her head in a decidedly negative manner.

"Tash!" cried the king.

"Who accuses you?”

"There are some things possible, madam, and some impossible. Among the impossible ones is that you should dream for a single moment of thwarting us and our purposes."

"I have no intention," began the queen meekly.

"Tash! Enough. There needs no protestations; but, as we say, one thing suggests another. We want to know what has become of two dead bodies which have mysteriously disappeared. The key to the enigma, could we find it, might unlock both the mysteries."

"I scarcely comprehend, sir—"

"Bah! Of course you do not. But since one of those dead men was brought into this portion of the palace—"

The queen gave a slight start.

"Ah!"

"I thought I heard a noise, sir, on the back stairs."

The king put both his hands behind his ears, and assumed an attitude of listening that was wonderfully grotesque.

He looked like a modern personification of one of those hideous old satyrs with which the strange mythology of the Greeks peopled the woodland haunts of their rocky isles.

"It is nothing. But, as we say, one of my dead men was brought in here. I do not accuse— Tash! that would be absurd. Madam, understand me. I do not say you know, but I want you to try and find out, as a woman may among women, the heart and kernel of this mystery."

The queen could not help drawing a long breath of relief.

She had been terrified at the idea that the king was about to order a minute search throughout the whole of that portion of the palace. She felt quite happy at being rescued from such a catastrophe.

"Your Majesty may depend that I will do my very best to discover everything your Majesty pleases, and as the hour is late, and I have still my devotions to—"

"Bo! stuff! We have something more to say."

The king looked down on the floor, and his countenance seemed to darken, and his small ferret eyes to dart forth malignant rays, as he seemed to be arranging some special villany—doubtless he would call it policy in his own mind.

The queen could scarcely forbear from trembling, for only once before had she seen those looks on the face of the king, and they had then preceded such a storm of vindictive rage that she wished never to look upon its like again.

It was something quite startling to her, then, to hear the low and scarcely articulate tones in which he spoke.

"There is more woman's wit wanted. We—we—ugh! ugh! ugh!—that is, we, in our compassion—for are we not the father of our people?—we—we—we—we—"

The king paused.

Nothing could be more evident than that he had something terrible to say, the actual utterance of which, in its bore and true significance, even he shrank from with a kind of natural horror.

The queen trembled more and more.

What could he be about to say?

What to propose?

He spoke again.

"We have duties—we have compassions—we are at once tender and strong. There is a young girl, almost a child. She—she—she was in care, or keeping, or something of first one and then the other of the arch- traitors we spoke of. We want her—we want her. We do not war with the weak, the childlike, and the destitute. We want her, that we may be merciful, great, and compassionate, as becomes a king—a king. We want her—ugh! ugh! ugh!—we want her—we—we want her. Madam, we want her."

"Sir?"

"Well?"

"Your Majesty was speaking of—of—"

"Of a young girl, almost a child. Well, what then? She is hidden—hidden from us, either in Whitehall or St. James's. Find her, find her. There is work, madam, for your woman's wit."

"Your Majesty wishes, then, to—to—"

"To what?"

"Provide for this—"

"Ha! ha! Have we not said so?—provide for her? Yes. Provide for her—ugh! ugh! ugh! —provide—provide for life."

The queen shuddered, and shrank further back.

The king projected his face forward, and stretched his long thin meagre hands across the table.

"It is necessary, madam, that this girl be found. Employ what tools or instruments you will, or go yourself about the task, for I must have her."

"Her name?" faltered the queen.

"Bertha."

The queen felt faint.

"You comprehend me, madam? You comprehend me? If it cost half a year's revenues of this kingdom, I must have my two dead men and mv one living girl. Accomplish this for us, and then ask what you will. You want to go to Mechlenburg—I know it—and you don't want to come back again. Ugh! ugh! ugh!"

The queen began to cry.

"Tash! We hate tears. Find for us our two dead men, and place in our fatherly care the young girl we speak of, and you may go—go at once. Ugh! ugh! ugh!"

There was a slight tap now at one of the doors of the queen's cabinet, and the king glanced towards it suspiciously, as he made a movement of his legs which would enable him, if necessary, to screen himself behind a chair on the smallest possible notice.

CHAPTER XLIV.

THREE CUPS OF COFFEE.

The tap at the door of the royal cabinet was repeated.

It was not etiquette for either the king or the queen to cry out, "Come in!" but it was a generally under stood thing that if the page in waiting gave three taps, and then found that the door would open to his hand, he was at liberty to enter and make any necessary announcement.

Those announcements were rare and long between.

It was only actual members of the royal family who could thus, without some prearrangement, intrude upon the royal privacy.

And now came the third tap. It was not the page of the back stairs (Mr. Osborn) who was demanding admission, but one of the other queen's pages on duty, who approached the private cabinet from quite another direction.

Then the page entered, and, with a low bow, was about to say something to the queen, when he nearly stumbled with surprise at the sight of the king.

It was then quite sufficiently evident that the page considered what he had to say would be distasteful to the king, for he tried to back out of the royal presence without saying it at all.

"Halt! Stop!"

The page paused and bowed low again.

There was no resource but to utter the message, whatever it was.

The queen shook with an undefined fear, and probably the placid Caroline had never endured in all her life such exquisite torment as during that interview with the king, who at any moment, if the whim should seize him, might, by walking six paces into the oratory, find himself in the midst of some of the very people to discover whom he was calling upon her to exercise her woman's wit.

The page spoke in a rather confused tone.

"May it please your Majesty, his Royal Highness Prince Frederick—"

"Ah!"

The king sprang to his feet.

"His Royal Highness the Prince Frederick presents his respectful duty to her Majesty, and requests the favour of a few minutes' audience."

The king darted an angry look at the queen.

"Indeed, indeed," she cried, "I did not expect him."

"Tash! What matters? We will go by the back stairs, or step into the oratory.

The queen could not suppress a scream.

The king turned fiercely towards her, and it would then appear that Caroline, simple as she looked, had more woman's wit than people gave her credit for.

She put on an expression of physical suffering, and sank back into her chair. "That sprain again!"

"What sprain?"

"On the stone staircase this morning, as I mentioned to you, sir."

"Bah! It will soon be well. We will step into the oratory, and perhaps—"

The queen screamed again.

His most gracious Majesty King George the Second was not at that moment exactly aware that two swords were half drawn from their scabbards in that oratory, and that if he had even ventured to cross its threshold he would have found himself a prisoner.

But that was not to be.

The king paused.

He placed his finger sagaciously by the side of his nose.

"Humph! Ugh! ugh! ugh!"

The king evidently had an idea.

What could it be?

He had been long at variance with his amiable son, Prince Frederick.

Was the father's heart relenting?—for even kings have father's hearts—and did he think this a favourable opportunity of making peace with his son and successor?

Surely, yes. It must be so.

What other motive could his most gracious Majesty have in using the words he did?

"Let him come. We will see him. Ugh! ugh! ugh! The family dissensions of monarchs set bad examples to their subjects. Let him come. We will see our son Frederick, even if it be for the last time. Ugh! ugh! ugh!"

The queen turned paler and weaker.

She was beginning to feel herself quite unequal to the task of sustaining that anxious scene much longer.

But how was she to escape from it without risking bringing about the very catastrophe the dread of which was making her sick and ill.

No.

She could do nothing.

She must wait—wait like some one tied to a rack of mental torment from which there was no escape.

"Yes—ugh! ugh!—we will see Frederick. Why not? And we will look upon this visit, late as it is, to you, madam, his mother, as some indication that lie repeats of the wickedness of his ways, and yearns for peace and family affection. Ugh!"

p. 227

The king's face, as he uttered these words, "family affection," was a perfect picture.

A picture at once grotesque and horrible.

He sat far back in the depths of an easy chair, and, crossing his thin legs one over the other, he waited for Frederick.

What was to be the issue of all this the queen had not the remotest idea, but she understood perfectly well that Frederick was to be admitted, and she gave, in a few words, the necessary order to the page.

There was a sharp quick footstep, and in another moment the prince and heir apparent to the throne appeared on the threshold of the private cabinet.

Frederick had not encountered his father since they had met at Whitehall, and of all persons else, he might, like Macbeth with Macduff, have avoided him.

The prince perfectly reeled in his effort to step back when he saw the king seated, with a grim smile upon his countenance, in that apartment.

But he had advanced rather too far for a precipitate retreat.

The page had closed the door respectfully and noiselessly behind him.

Then the king spoke.

"Frederick, these dissensions grieve us—grieve us to our inmost heart."

The prince put his hand to his sword.

"Yes, they grieve us," added the king, "and if, like the prodigal son, you return to us this night, Frederick, why should we not—ugh! ugh! ugh!—why should we not—"

The king glanced at the queen as though she were the fatted calf which was to be killed and eaten on the occasion of the blessed reconciliation between himself and his son.

But Frederick did not see things in the same light— or rather he judged of things by many former lights—or he kept himself carefully on his guard, and every now and then turned completely round, like some one caught in a trap, or as though he expected some covert attack from behind him.

"And why not?" added the king, affecting to speak with emotion. "Why should there not be peace and concord among us, now that we are seated firmly on the throne of this kingdom?"

"I came," said Frederick, "to pay my humble duty to the queen."

"Delightful word!" ejaculated the king. "I like that word 'humble.' It betrays a contrite spirit."

"Sir!"

"Our son!"

"Sir!"

"Our Frederick, it would be too much for our feelings at present, but we will embrace you to-morrow."

Frederick glanced at the window, as though he would gladly have left the cabinet by that means, if it were possible.

"Yes, we will embrace you to-morrow. At present it would be too much for our royal feelings—we mean our fatherly feelings—and as the hour is late, and it would be far from wise to partake of any stimulating liquid, we will only inaugurate this happy reconciliation by a cup of coffee."

The strange look upon the king's face as he uttered the words "cup of coffee" would be quite impossible to describe.

He seemed to have one eye upon the prince, while the other was fixed upon the ceiling above him, and the odd manner in which one corner of his mouth was drawn down to correspond with the eye which was upon the prince was intensely ludicrous.

"A cup of coffee?" ejaculated the queen, as if in doubt whether it could be procured.

"A cup of coffee?" said the prince, as though he were diving into his mind to discover what amount of danger he was about to be subjected to.

"A cup of coffee," added the king. "We will have coffee. It is a rare and delicious beverage, and we are told is making its way rapidly among all the wits and philosophers of the age. Ugh! ugh! ugh! We will have a cup of coffee, each of us, to commemorate this happy reconciliation." The queen gave a slight touch to a silver bell.

The page in waiting appeared.

"His Majesty desires coffee."

The page bowed his exit, and no doubt gave the necessary order to somebody else, who passed it on to another person, and so until it would reach the actual preparer of the royal coffee.

"Sit down, Frederick. Ugh! ugh! Sit down at ease, our son. You look but pale and sickly. Alas! we are ourselves at times but weak and poorly. What would become of this realm, Frederick, if, as people say, anything were to happen to both of us?"

"I trust," said Frederick, "that your Majesty will live long and die de—that is to say, happy." Was the word "detested" on Frederick's lips?"

The one syllable was suggestive.

"A thousand thanks," replied the king, "but human life—ugh! ugh!—is on uncertain possession, and sometimes the scarred and tempest-torn old oak outlives the vigorous sapling. Ugh! ugh! You look like a sapling, Frederick—you look like a sapling."

The prince grew more uneasy each passing minute.

He had seated himself but upon the extreme edge of a chair, but now he suddenly rose with a jerk.

"I will no longer intrude upon your Majesty."

"Intrude? Intrude?"

"Yes. The hour, as your Majesty has remarked, is late. I shall sleep the better for this happy reconciliation, and to-morrow I shall hope to be able to say some thing to cement it and render it more durable."

The door of the cabinet opened, even as Frederick spoke, and the page appeared, with a small golden tray, on which were three cups of the same metal.

The unmistakable aroma of coffee was in the air.

And here we may remark that the partaking of that sedative, or stimulant, or beverage—call it which we may—was either not so well understood at that period as at present, or a great deal better.

The gold cups in which it was brought to the queen's cabinet had no handles, but each of them was provided with an elaborately chased cover.

Three gold spoons, something in size between tea-spoons and desserts, lay on the tray.

With these spoons the coffee would have to be sipped from the cups, something after the manner of taking soup in small quantities.

"Delightful!" said the king. "Delightful! You shall not go, Frederick, until you have drunk with us some of this—this commemoration coffee. Ugh! ugh! ugh! Delicious! delicious! Are these the cups, madam, that the Russian ambassador brought, as a present from his imperial master? Beautiful! beautiful! Delicious! Ugh! ugh! ugh!"

The king had risen, and seemed to be brooding over the coffee tray as though performing some incantation. As he slightly stooped the wide stiff skirts of his coat spread out between the table and Frederick.

It was in vain that the latter twisted himself into all imaginable shapes, for the purpose of trying to get a peep, past the head or arm of the king, of what he was about.

It was but the action of a moment.

The king dived his hand into one of the capacious waistcoat pockets.

He got possession of a small round lozenge.

Another moment, and it fell into one of the cups of dark coffee, floating half round upon the pleasant liquid for an instant, and then sinking to the bottom of the cup.

"Ugh!"

Frederick looked ghastly.

There were the three cups, and, like the charmed bullets in the German legend, "two would go true, the other askew."

But which were the true ones?

How pleasant, rich, and harmless they all looked!

Or were two of those cups fatal?

Would the king hesitate to sacrifice the life of the queen, provided he comprehended in that sacrifice that of his son?

Or was the whole thing too monstrous to think or dream of? Were all the three cups harmless, and simply pleasant and invigorating? and was that apparent brooding of the king over the tray merely a passing admiration of the beautiful [chased] covers of the cups?

It might be so.

But then, again, it might not.

Did not Frederick feel, deep in the innermost recesses of his own heart, that he had made himself a party to the attempted assassination of his own father?

Why might not, therefore, that father, terrible as it was that such passions should be evoked between father and son, retaliate upon him?

A cold perspiration sat upon his brow. His knees trembled. He could hardly speak.

There was the one difference between Frederick and the king. No one doubted the more physical courage of the latter. No one doubted the abject cowardice of the former.

The king lifted off the cover of one of the cups, and took a spoon in his hand.

With an air of great affected gallantry, then he lifted another of the cups by its golden saucer, and handed it to the queen.

There was only another left.

That was Frederick's.

Was it Frederick's?

Not if all the world had combined, with all its persuasions and all its force, to induce him to drink it.

"Ugh! ugh!" said the king. "This is pleasant. This is the cup that—what does the fool call it?—the cup that cheers but not inebriates. Ugh! ugh! ugh! We drink to our happy future, Frederick, and to the peace of this our realm of England."

The prince made a desperate effort.

"I never felt so happy, sir, in all my life. It may very possibly be that some parts of my conduct may have been what your Majesty could not exactly—"

"Tash! Never mind."

"You are too good, sir."

"Let us cease compliments, Frederick, and drink our coffee. It is far better that the past should be forgotten."

"Those words are but another proof of your Majesty's goodness."

"Drink, Frederick! Drink!"

"Oh I certainly."

"Ugh! ugh! It wants stirring. I find stirring it wonderfully improves it."

The king slowly stirred his own coffee with the golden spoon, while he fixed his eyes steadily upon Frederick.

The prince must have made a great mental effort now to behave as he did, for he took the chaste cover off his cup with tolerable composure, and slowly he began to stir his coffee.

And so this father and son regarded each other, with the hateful light of murder in both their eyes and a hideous mocking smile upon their lips.

The queen was bewildered.

She had not the slightest idea of the hideous serio-comic tragedy which was being enacted before her eyes.

It had never entered into her placid imagination to suppose that, even at the height of their quarrels and dissensions, that father and son could ever think of contriving aught against each other's lives.

And so she looked on, in a kind of stupid blank amazement, and knew not what she looked at.

CHAPTER XLIV.

THREE CUPS OF COFFEE.

The tap at the door of the royal cabinet was repeated.

It was not etiquette for either the king or the queen to cry out, "Come in!" but it was a generally under stood thing that if the page in waiting gave three taps, and then found that the door would open to his hand, he was at liberty to enter and make any necessary announcement.

Those announcements were rare and long between.

It was only actual members of the royal family who could thus, without some prearrangement, intrude upon the royal privacy.

And now came the third tap. It was not the page of the back stairs (Mr. Osborn) who was demanding admission, but one of the other queen's pages on duty, who approached the private cabinet from quite another direction.

Then the page entered, and, with a low bow, was about to say something to the queen, when he nearly stumbled with surprise at the sight of the king.

It was then quite sufficiently evident that the page considered what he had to say would be distasteful to the king, for he tried to back out of the royal presence without saying it at all.

"Halt! Stop!"

The page paused and bowed low again.

There was no resource but to utter the message, whatever it was.

The queen shook with an undefined fear, and probably the placid Caroline had never endured in all her life such exquisite torment as during that interview with the king, who at any moment, if the whim should seize him, might, by walking six paces into the oratory, find himself in the midst of some of the very people to discover whom he was calling upon her to exercise her woman's wit.

The page spoke in a rather confused tone.

"May it please your Majesty, his Royal Highness Prince Frederick—"

"Ah!"

The king sprang to his feet.

"His Royal Highness the Prince Frederick presents his respectful duty to her Majesty, and requests the favour of a few minutes' audience."

The king darted an angry look at the queen.

"Indeed, indeed," she cried, "I did not expect him."

"Tash! What matters? We will go by the back stairs, or step into the oratory.

The queen could not suppress a scream.

The king turned fiercely towards her, and it would then appear that Caroline, simple as she looked, had more woman's wit than people gave her credit for.

She put on an expression of physical suffering, and sank back into her chair. "That sprain again!"

"What sprain?"

"On the stone staircase this morning, as I mentioned to you, sir."

"Bah! It will soon be well. We will step into the oratory, and perhaps—"

The queen screamed again.

His most gracious Majesty King George the Second was not at that moment exactly aware that two swords were half drawn from their scabbards in that oratory, and that if he had even ventured to cross its threshold he would have found himself a prisoner.

But that was not to be.

The king paused.

He placed his finger sagaciously by the side of his nose.

"Humph! Ugh! ugh! ugh!"

The king evidently had an idea.

What could it be?

He had been long at variance with his amiable son, Prince Frederick.

Was the father's heart relenting?—for even kings have father's hearts—and did he think this a favourable opportunity of making peace with his son and successor?

Surely, yes. It must be so.

What other motive could his most gracious Majesty have in using the words he did?

"Let him come. We will see him. Ugh! ugh! ugh! The family dissensions of monarchs set bad examples to their subjects. Let him come. We will see our son Frederick, even if it be for the last time. Ugh! ugh! ugh!"

The queen turned paler and weaker.

She was beginning to feel herself quite unequal to the task of sustaining that anxious scene much longer.

But how was she to escape from it without risking bringing about the very catastrophe the dread of which was making her sick and ill.

No.

She could do nothing.

She must wait—wait like some one tied to a rack of mental torment from which there was no escape.

"Yes—ugh! ugh!—we will see Frederick. Why not? And we will look upon this visit, late as it is, to you, madam, his mother, as some indication that lie repeats of the wickedness of his ways, and yearns for peace and family affection. Ugh!"

p. 227

The king's face, as he uttered these words, "family affection," was a perfect picture.

A picture at once grotesque and horrible.

He sat far back in the depths of an easy chair, and, crossing his thin legs one over the other, he waited for Frederick.

What was to be the issue of all this the queen had not the remotest idea, but she understood perfectly well that Frederick was to be admitted, and she gave, in a few words, the necessary order to the page.

There was a sharp quick footstep, and in another moment the prince and heir apparent to the throne appeared on the threshold of the private cabinet.

Frederick had not encountered his father since they had met at Whitehall, and of all persons else, he might, like Macbeth with Macduff, have avoided him.

The prince perfectly reeled in his effort to step back when he saw the king seated, with a grim smile upon his countenance, in that apartment.

But he had advanced rather too far for a precipitate retreat.

The page had closed the door respectfully and noiselessly behind him.

Then the king spoke.

"Frederick, these dissensions grieve us—grieve us to our inmost heart."

The prince put his hand to his sword.

"Yes, they grieve us," added the king, "and if, like the prodigal son, you return to us this night, Frederick, why should we not—ugh! ugh! ugh!—why should we not—"

The king glanced at the queen as though she were the fatted calf which was to be killed and eaten on the occasion of the blessed reconciliation between himself and his son.

But Frederick did not see things in the same light— or rather he judged of things by many former lights—or he kept himself carefully on his guard, and every now and then turned completely round, like some one caught in a trap, or as though he expected some covert attack from behind him.

"And why not?" added the king, affecting to speak with emotion. "Why should there not be peace and concord among us, now that we are seated firmly on the throne of this kingdom?"

"I came," said Frederick, "to pay my humble duty to the queen."

"Delightful word!" ejaculated the king. "I like that word 'humble.' It betrays a contrite spirit."

"Sir!"

"Our son!"

"Sir!"

"Our Frederick, it would be too much for our feelings at present, but we will embrace you to-morrow."

Frederick glanced at the window, as though he would gladly have left the cabinet by that means, if it were possible."

Yes, we will embrace you to-morrow. At present it would be too much for our royal feelings—we mean our fatherly feelings—and as the hour is late, and it would be far from wise to partake of any stimulating liquid, we will only inaugurate this happy reconciliation by a cup of coffee."

The strange look upon the king's face as he uttered the words "cup of coffee" would be quite impossible to describe.

He seemed to have one eye upon the prince, while the other was fixed upon the ceiling above him, and the odd manner in which one corner of his mouth was drawn down to correspond with the eye which was upon the prince was intensely ludicrous.

"A cup of coffee?" ejaculated the queen, as if in doubt whether it could be procured.

"A cup of coffee?" said the prince, as though he were diving into his mind to discover what amount of danger he was about to be subjected to.

"A cup of coffee," added the king. "We will have coffee. It is a rare and delicious beverage."

The page in waiting appeared.

"His Majesty desires coffee."

The page bowed his exit, and no doubt gave the necessary order to somebody else, who passed it on to another person, and so until it would reach the actual preparer of the royal coffee.

"Sit down, Frederick. Ugh! ugh! Sit down at ease, our son. You look but pale and sickly. Alas! we are ourselves at times but weak and poorly. What would become of this realm, Frederick, if, as people say, anything were to happen to both of us?"

"I trust," said Frederick, "that your Majesty will live long and die de—that is to say, happy." Was the word "detested" on Frederick's lips?"

The one syllable was suggestive.

"A thousand thanks," replied the king, "but human life—ugh! ugh!—is on uncertain possession, and some times the scarred and tempest-torn old oak outlives the vigorous sapling. Ugh! ugh! You look like a sapling, Frederick—you look like a sapling."

The prince grew more uneasy each passing minute.

He had seated himself but upon the extreme edge of a chair, but now he suddenly rose with a jerk.

"I will no longer intrude upon your Majesty."

"Intrude? Intrude?"

"Yes. The hour, as your Majesty has remarked, is late. I shall sleep the better for this happy reconciliation, and to-morrow I shall hope to be able to say some thing to cement it and render it more durable."

The door of the cabinet opened, even as Frederick spoke, and the page appeared, with a small golden tray, on which were three cups of the same metal.

The unmistakable aroma of coffee was in the air.

And here we may remark that the partaking of that sedative, or stimulant, or beverage—call it which we may—was either not so well understood at that period as at present, or a great deal better.

The gold cups in which it was brought to the queen's cabinet had no handles, but each of them was provided with an elaborately chased cover.

Three gold spoons, something in size between tea-spoons and desserts, lay on the tray.

With these spoons the coffee would have to be sipped from the cups, something after the manner of taking soup in small quantities.

"Delightful!" said the king. "Delightful! You shall not go, Frederick, until you have drunk with us some of this—this commemoration coffee. Ugh! ugh! ugh! Delicious! delicious! Are these the cups, madam, that the Russian ambassador brought, as a present from his imperial master? Beautiful! beautiful! Delicious! Ugh! ugh! ugh!"

The king had risen, and seemed to be brooding over the coffee tray as though performing some incantation. As he slightly stooped the wide stiff skirts of his coat spread out between the table and Frederick.

It was in vain that the latter twisted himself into all imaginable shapes, for the purpose of trying to get a peep, past the head or arm of the king, of what he was about.

It was but the action of a moment.

The king dived his hand into one of the capacious waistcoat pockets.

He got possession of a small round lozenge.

Another moment, and it fell into one of the cups of dark coffee, floating half round upon the pleasant liquid for an instant, and then sinking to the bottom of the cup.

"Ugh!"

Frederick looked ghastly.

There were the three cups, and, like the charmed bullets in the German legend, "two would go true, the other askew."

But which were the true ones?

How pleasant, rich, and harmless they all looked!

Or were two of those cups fatal?

Would the king hesitate to sacrifice the life of the queen, provided he comprehended in that sacrifice that of his son?

Or was the whole thing too monstrous to think or dream of? Were all the three cups harmless, and simply pleasant and invigorating? and was that apparent brooding of the king over the tray merely a passing admiration of the beautiful chased covers of the cups?

It might be so.

But then, again, it might not.

Did not Frederick feel, deep in the innermost recesses of his own heart, that he had made himself a party to the attempted assassination of his own father?

Why might not, therefore, that father, terrible as it was that such passions should be evoked between father and son, retaliate upon him?

A cold perspiration sat upon his brow. His knees trembled. He could hardly speak.

There was the one difference between Frederick and the king. No one doubted the more physical courage of the latter. No one doubted the abject cowardice of the former.

The king lifted off the cover of one of the cups, and took a spoon in his hand.

With an air of great affected gallantry, then he lifted another of the cups by its golden saucer, and handed it to the queen.

There was only another left.

That was Frederick's.

Was it Frederick's?

Not if all the world had combined, with all its persuasions and all its force, to induce him to drink it.

"Ugh! ugh!" said the king. "This is pleasant. This is the cup that—what does the fool call it?—the cup that cheers but not inebriates. Ugh! ugh! ugh! We drink to our happy future, Frederick, and to the peace of this our realm of England."

The prince made a desperate effort.

"I never felt so happy, sir, in all my life. It may very possibly be that some parts of my conduct may have been what your Majesty could not exactly—"

"Tosh! Never mind."

"You are too good, sir."

"Let us cease compliments, Frederick, and drink our coffee. It is far better that the past should be forgotten."

"Those words are but another proof of your Majesty's goodness."

"Drink, Frederick! Drink!"

"Oh I certainly."

"Ugh! ugh! It wants stirring. I find stirring it wonderfully improves it."

The king slowly stirred his own coffee with the golden spoon, while he fixed his eyes steadily upon Frederick.

The prince must have made a great mental effort now to behave as he did, for he took the chaste cover off his cup with tolerable composure, and slowly he began to stir his coffee.

And so this father and son regarded each other, with the hateful light of murder in both their eyes and a hideous mocking smile upon their lips.

The queen was bewildered.

She had not the slightest idea of the hideous serio-comic tragedy which was being enacted before her eyes.

It had never entered into her placid imagination to suppose that, even at the height of their quarrels and dissensions, that father and son could ever think of contriving aught against each other's lives.

And so she looked on, in a kind of stupid blank amazement, and knew not what she looked at.

CHAPTER XLV.

A DISCOVERY.

It was rather dexterous of Frederick.

He sat with his back towards the door of the cabinet by which he had entered it.

Quietly and covertly he took from his pocket a rather heavy gold snuff-box, and flinging it backward with as much force as he could command, it struck heavily against one of the panels of the door.

Now this private cabinet of the queen was carpeted with extremely thick Persian velvet, so that after the prince's gold snuff-box had struck the door panel it fell quite noiselessly.

We have before remarked upon the extreme gloom of the apartment, in consequence of the very small amount of light which the queen had in it, and which she had merely intended to be sufficient to enable her to read her devotions.

This gloom then enabled Frederick to perform the little manoeuvre we have recounted without observation.

The blow upon the panel of the door had all the effect, although it was from within, as if had been without.

The king was startled. But it was the few words uttered by the prince, in conjunction with the noise on the panel, that produced all the desired effect upon him.

"Now they come!" cried Frederick, as he sprang to his feet. The king raised a yell, and put himself on his guard. The impression was immediate and complete. And that impression was just this:—

Frederick had known he was in the queen's cabinet.

He had come there to seek him.

He had only waited so long, until, by a signal, he knew that his friends and fellow-conspirators were ready to rush in and complete the work which they had left unfinished at Whitehall.

"Treason! treason! help!" shouted the king.

"Help! Treason! treason! treason!"

The door of the cabinet was flung open, and the bewildered page in waiting stood there with his eyes preternaturally wide open, and his half-drawn sword in his hand.

All without was as peaceful and quiet as possible.

But it must have been a rather extraordinary group in the queen's cabinet that met the eyes of the page.

The king stood, with his drawn sword in his hand, fully and firmly on the defensive.

Prince Frederick, with a face as white as any plaister statue, was close to the coffee table.

The queen was showing symptoms of fainting and hysterics.

"What? What is it?" gasped the king.

"Your Majesty cried 'Treason!'"

"Yes. Treason! treason! We cried treason."

"There is no one here, your Majesty."

"No one?"

The king lowered the point of his sword.

He slowly turned on his heels towards Frederick.

"What was it?"

The prince shook his head.

"What was it? You said 'Now they come!'"

"Pardon me, sir, but I feared—"

"You feared what?"

"Still pardon me, your Majesty; but I heard a noise, and I feared that, justly incensed against me for some errors of the past, your Majesty had found some means of summoning a guard, and the Tower of London might be my lodging-place to-night. Oh! pardon me, sir, if I have done you an injustice, but I have found it so difficult suddenly to believe in your Majesty's clemency that, like the poor thief who knows his own guilt, and sees in each dubious shadow an officer of justice, every slight alarm startles me into a fear of some just retribution."

The prince bowed low as he spoke. The king made a movement of his arm, and the page closed the door.

"Humph! Ugh! ugh! ugh! That's it?"

"It is so, sir."

"Why—why, then—then we will take our coffee. Ugh! ugh! ugh! We will take our coffee."

p. 228

The king dallied with his spoon.

Frederick deliberately stirred his coffee, and began to sip it with all the calmness in the world; only he still looked very white and statuesque as to colour.

Then an awful change came over the face of the king. He slowly turned over and over the spoon he held in his hand.

It was not the same one!

Not the same one he had before used, for there happened to be a peculiarity, a kind of indentation, in the bowl of it which was not there before

The prince had changed the cups.

The king was as confident of that fact as though he had actually seen him do it. What an awful game of life and death was that!

Now the advantage on one side, then on the other.

"What was to happen next?

There was a bright red spot in the face of the king.

It was the hectic of violent suppressed passion.

But he still succeeded in suppressing it.

"Ugh! ugh! ugh! Frederick, our son, this is a delightful evening. Ah! the queen faints!"

"No," said the queen faintly.

"Some water! some water! Frederick, go and speak to the page on duty. How absurd! We were about to sprinkle her face with hot coffee! Water, Frederick, cold water! Speak to the page on duty."

The prince rose, with a groan.

Well, he knew what was going to happen. But he could not help himself.

His absence was but that of half a minute, and during that time the cups were changed once more.

The water was brought, and the queen opened her eyes again.

Frederick glanced at the coffee table. He did not take the least trouble to assure himself of the change that had been effected by any minute evidence such as had struck the king.

He was quite satisfied on the subject. But he by no means gave himself up for lost on that account.

It was by no means a trial of strength, but it was one of wit—or, perhaps we should say, of wickedness.

The prince now played his last stake, and a good one it was.

He turned from the queen to say something to the king.

His foot slipped (it was very well done indeed, and looked exceedingly accidental), he fell bodily against the coffee table, and tray and cups and spoons and saucers and coffee were upset at once to the floor of the cabinet.

The shock of this uproar seemed to do more to recover the queen than the cold water, for she uttered two or three screams and sprang to her feet.

There was a look of terrible concentrated malignity on the face of the king.

Did he comprehend exactly what had happened?

Who shall doubt it?

He took three strides towards the door. The game was over, and there was no longer occasion for him to remain.

It was not exactly a defeat, but a drawn battle—a fight for life and for death which might be resumed on another occasion.

"Good night, madam," he said, "and good night to our dear Frederick. Remember, madam, the commission we have entrusted to your care. Remember its importance and its reward."

The king abruptly left the cabinet. Prince Frederick was, if possible, on worse terms with his mother than with his father. His errand to her on that night had been to borrow some money, but after what had happened he saw that she was in no state to listen to him, and, turning on his heel, he left the cabinet without even going through the ceremony of bidding her good night.

Then the queen, with various ejaculations and in coherent expressions of thankfulness that she had got rid of both her tormentors, rushed to the oratory.

"Come forth! come forth!" she cried. "On! come forth, and fly, all of you. There is no peace, no safety here."

Bertha was clinging to Captain Markham, and there was a look of high excitement on her face.

Agnes Bellair seemed quite overcome by the terrible character of that interview between the father and son, which had taken place within a few paces of them.

"You must fly at once," continued the queen. "You know there is no peace nor safety for you here. You have heard what the king knows, and what he wishes me to do."

"We have, indeed, madam," replied Markham, "and Heaven preserve you from such a—"

"No, no," interrupted the queen. "You must not speak of him. Say nothing of him, but fly from here, and insure your own safety."

"I am ready," said Bertha.

"With me for ever!" whispered Markham.

"For ever and for ever!"

"There is no occasion," added the queen, "for the Marquis of Charlton or for Agnes to take the least notice of all these proceedings. Their union can take place as a thing of course, and I will do what I can to protect them and ensure their happiness. Heaven knows how little that is; for what am I? Oh! what am I?"

The queen showed symptoms of giving way to some passionate burst of grief; but, both Agnes and Bertha spoke gently to her, and she succeeded in controlling herself.

Then there was a slight scratching noise at that door which led to the back stairs.

It was Mr. Osborn, the page.

They all looked inquiringly into the somewhat anxious face of this youth, who addressed himself to the Marquis of Charlton.

"Colonel," he said, "there is a drummer of the guard, of the name of Dick Martin. He seems in great distress about something, and insists on seeing you."

"It is the lad," said Markham, "whom I sent to Whitehall in search of you, Bertha, at a time when I believed that death would interpose between us, at all events in this world, and deprive me of the power to protect you."

Bertha only clung closer still to Markham's arm, and said nothing.

"The boy is so clamorous, colonel," added Mr. Osborn, the page, "that I thought it might be of some moment you should sее him."

"Bring him here," said the queen. "All these matters seem connected with each other, and he may have something to say which will be an element in your safety."

The page bowed and departed on his errand.

"It would be better," said the Marquis of Charlton, "to leave me alone to speak to him. We need not burden a lad like that with more secrets than necessary."

"Assuredly," said Markham. "That is well thought of. We will retire again to the oratory."

For a few seconds more there was no one in the cabinet but the queen and the Marquis of Charlton. With a look of amazement and something of fright on his countenance, Dick Martin was ushered in by Mr. Osborn.

As soon as he saw the marquis he drew himself up to attention, and saluted.

"Well, Dick, what is it? You wanted to see me."

"Yes, your honour."

"Speak out, and quickly."

The boy glanced at the queen, but, in the quiet costume in which she was, he had not the least idea of her rank.

"Oh! never mind, Dick. She is only a lady before whom you may speak freely."

"Yes, your honour. I don't know whether I'm doing right or wrong, but it's about Captain Markham I want to speak."

"I will take upon myself to say," replied the marquis, "that Captain Markham has no truer friend than myself. So you may speak freely, Dick."

"I will, then, your honour. The captain gave me orders to go to Whitehall and to try and find there a young lady, and to tell her to take care of herself, and fly from England as quickly as possible, for he could no longer protect or save her."

"You did not find her, Dick?"

"No, your honour. I went through the old galleries and the deserted rooms, and up and down the great staircases, and every now and then I gave a few raps upon my drum, with the hope that they would let her know that somebody was looking for her; but I found nothing of her."

"Make your mind easy, Dick. She is safe and well cared for."

"But, colonel—"

"Well, Dick?"

"I found some one else, your honour. There is a gentleman there, badly wounded. He looked like a ghost, and I was half afraid to follow him; but when I did I found that he was like ourselves, and only weak and pale and badly hurt. I asked him who he was, and he looked so faint and could scarcely speak, and said he was A Mystery in Scarlet."

(To be continued in our next.)