Exhibit:

The Were-Wolf by Clemence Housman was first published as a stand-alone illustrated novella in 1896 by John Lane at The Bodley Head in London, England. The work was produced collaboratively by Clemence and her younger brother Laurence Housman, an established visual artist and author. Laurence designed six full-page illustrations to the text as well as the title page, the initial letter, and the bindings. As a skilful craftswoman, Clemence wood-engraved her brother’s illustrations by hand to be reproduced for the completed publication.

The novella made its debut at a time when challenging sociopolitical concepts of gender began to pervade public discourse. The rising women's suffrage movement, and their campaign for equal enfranchisement at the fin-de-siècle, inspired a necessary reform on the Victorian public's understanding of conventional roles for women. Both Clemence and Laurence Housman were devoted activists participating in this movement, notably as co-founders of the Suffrage Atelier (1909).

The novella made its debut at a time when challenging sociopolitical concepts of gender began to pervade public discourse. The rising women's suffrage movement, and their campaign for equal enfranchisement at the fin-de-siècle, inspired a necessary reform on the Victorian public's understanding of conventional roles for women. Both Clemence and Laurence Housman were devoted activists participating in this movement, notably as co-founders of the Suffrage Atelier (1909).

The publication of The Were-Wolf (1896) as a stand-alone illustrated edition presented Clemence Housman with the opportunity to critically link her steadfast activism to her specialized art and trade. Although the craft of wood engraving exists in the background of the novella’s narrative action, it is strategically represented by Housman in illustration and in text. Moreover, the significance of wood engraving to The Were-Wolf and the ideologies it represents should not be hastily dismissed. This analysis aims to demonstrate how wood engraving as a medium for image reproduction enabled Clemence Housman to extend the meaning of her narrative beyond mere entertainment, and participate in a powerful social conversation that directly impacted her identity as a female creative.

Figure 1. Title-page of The Were-Wolf published by John Lane at The Bodley Head (1896)

Clemence Housman’s Contributions (1861-1955)

Clemence (Annie) Housman was born on November 23rd, St. Clements' day, in 1861. She was raised in Bromsgrove, Worcestershire, but spent the majority of her early life living with family in Perry Hall (Khan). Of her six siblings, Clemence was closest to her younger brother Laurence (1865-1959), accomplished book designer, artist, author, and activist, whom she went on to live and collaborate with her entire adult life. In 1883, Clemence moved to London with Laurence under the guise of acting as his domestic housekeeper, but used this opportunity mainly to advance her artisanal skills and participate in relevant social activism (Kooistra 286).

Housman began her study in wood engraving at the City and Guilds South London Technical Art School, formerly known as the Lambeth School of Art, taking gender-segregated classes for female wood engravers (Khan). Her aptitudes were quickly recognized by teachers, and within two years opposed to the typical five to seven, had successfully completed her training (Kooistra 287). Housman’s early workplace involvement included wood-cutting for the Illustrated London News (1842–1989) and the Graphic (1869–1932). Due to growing developments in photomechanical technology and the decreased demand for wood-engraved reproductions towards the end of the 19th century, she relied mainly on her brother’s connections in the “book arts network” to continue her career (Kooistra 286). In these later years, Housman worked as a wood engraver for fine arts presses and publishers such as The Bodley Head, and also had work featured in various little-magazines including The Venture (1903).

Figure 2. Postcard featuring the "From Prisonhood to Citizenship" by Clemence Housman after Laurence Housman's design at the Suffrage Atelier. Public Domain.

Figure 3. Occupations for Women Other than Teaching. Pamphlet in Mark Samuels Lasner's Collection at University of Delaware Library containing Clemence Housman's essay on Wood Engraving as an Occupation for Women (1887).

Around the same time that Housman established herself as a remarkably skilled wood engraver, she also claimed status as an avid activist for women’s rights. The campaign for Victorian women’s suffrage, which began in 1866 and reached new heights at the fin-de-siècle, aimed to reform traditional notions of gender, femininity, and sexuality in order to end the oppression of women and achieve equal enfranchisement (Smith 8). Suffragists demonstrated to abolish gender-biased restrictions on women’s education, employment, salary, legal authority, (Smith 3) and worked strategically restructure the way modern women viewed their social opportunities and standing.

Participating in this movement, Housman eagerly engaged in activism with her dedication to craft in mind. In 1887, she contributed an essay titled "Wood Engraving" to the informative pamphlet Occupations for Women, Other Than Teaching which was printed for the Association of Assistant-Mistresses (Kooistra 287). In her essay, Housman argued that the segregation of genders in wood-engraving training not only disadvantages craftswomen, but dangerously reinforces unequal gender relations in the workforce. Additionally, Housman worked with her brother’s designs to embroider banners and broadsheets for suffrage demonstrations between 1908 and 1914 (Tickner 21), and in 1909, the siblings established the Suffrage Atelier from their small cottage home in Kensington. The Suffrage Atelier, active from 1909 to 1914, was a feminine arts and crafts collective which worked to forward the suffrage campaign by disseminating feminist art and propaganda handmade by women (Tickner 25). Housman’s work with the Suffrage Atelier functioned to provide a range of female artists with the opportunity to voice their ideas on gender and social identity through arts and crafts.

Victorian Wood Engraving

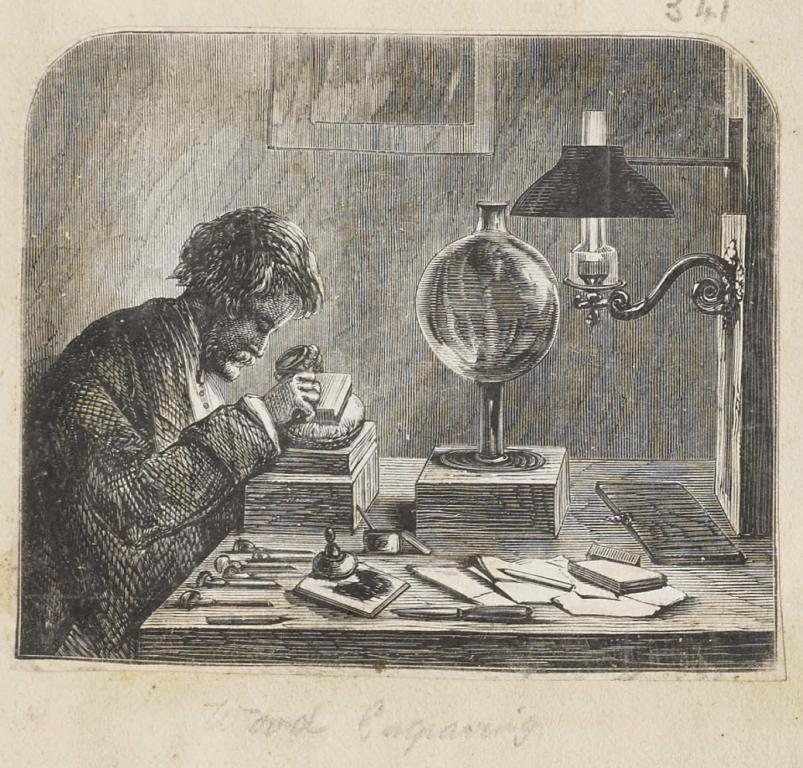

To understand the significance of The Were-Wolf’s illustrations, the technology that is so intimately connected to its production must first be considered. Wood engraving was recognized as an imaging technology capable of mass reproduction towards the end of the 18th century, pioneered by the innovation of Thomas Beswick (1753-1828). Rather than perceiving the surface area of the hardwood block as white on which black lines were to be drawn and then engraved, Beswick imagined the woodblock as black and the lines as white (Sander 16). Since this method was based upon digging out the negative spaces or “whites” of a design, wood engraving was colloquially known as the “art of the white line” (Hunsberger).

Wood engraving was further revised and developed early in the 19th century, revolutionizing the production of images in print media. This type of wood engraving differed from the earlier “woodcut” technique which utilized the plank surface of the boxwood opposed to the end-grain. The end-grain, capable of very fine detail, reproduced images so refined that they could be compared to those produced by copper and steel (Stevens). Wood engraving was also recognized as a much more feasible and efficient alternative to other methods since woodblocks could be set up with plates of type and reproduced with any kind of relief-based letterpress (Sander 19). Due to these idealistic qualities, wood engraving virtually dominated the Victorian illustrated book industry until it was eventually replaced by developments in photomechanical imaging.

Figure 4. "Wood Engraving," from the Woodpeckings Archive. Public Domain.

At its height of popularity, wood engraving was industrialized to accommodate the increasing demand for printed images. This shift brought upon the formation of large engraving firms, reliant on a system of division of labour, such as the Dalziel Brothers firm in London (Stevens). However, the virtues of wood engraving in these reproductive art factories greatly differed from those possessed by artist and pioneer Thomas Beswick, who “engraved to demonstrate, to breathe life into the picture he was making,” and worked “to keep the act of engraving meaning meaningful and creative” (Sander 16). Due to the industrialized nature of these firms, the laborious and dedicated works of wood engravers went largely uncredited. In the case of The Dalziel Brothers firm, all employees problematically signed their work “Dalziel,” and were never individually recognized for this reason (Stevens 4). This absence of credit is not uncommon to the wood engraver, who essentially made their business by artistically producing someone else’s designs and “carving other people’s signatures” (Stevens 4).

In the case of Clemence Housman, the methods that situated her among the most skilled wood engravers of the 19th century also worked to make her "virtually invisible in the history of print” (Kooistra 277). This was the unfortunate reality of many other craftswomen whose work was never acknowledged and credited to them. Though despite the absence of the engraver’s signature from the woodblock, their work will never be entirely anonymous. Beswick’s innovation established a form of artistic expression that inherently marked the engraver’s medium with their identity. As a linear art, the wood engraver communicated image, shape, and shade by engraving a series of lines. Moreover, it can be said that the line is the foremost mark of the engraver: it is simultaneoulsy a “signature" and a "self-portrait” (Stevens 9). By examining the line, the relationship of the engraver to the “visually different, more abstract world” of the woodblock that only they experienced first-hand can be understood (Stevens 18).

The Were-Wolf (1896)

Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf originated as an oral tale which she invented in 1884 with the intent of entertaining her fellow female wood-engraving students at the South London Technical Art School. Housman's narrative was met with success, according to Laurence who reported that she “captivated” and “thrilled” her audience (Natt). The Were-Wolf was officially published in the 1890 Christmas supplement to the monthly girl’s periodical, Atalanta, where it reached new heights of success (Kooistra 291). The growing popularity of Housman's tale subsequently inspired John Lane at The Bodley Head to publish The Were-Wolf in 1896 as a part of his belles-lettres series. Unlike it's original publication in magazine form, The Bodley Head edition was published as a stand-alone novella with six full-page illustrations and decorations all expertly engraved by Clemence after her brother’s designs. Throughout this edition, wood engraving is continually assserted by Housman as a valuable craft and medium for expression.

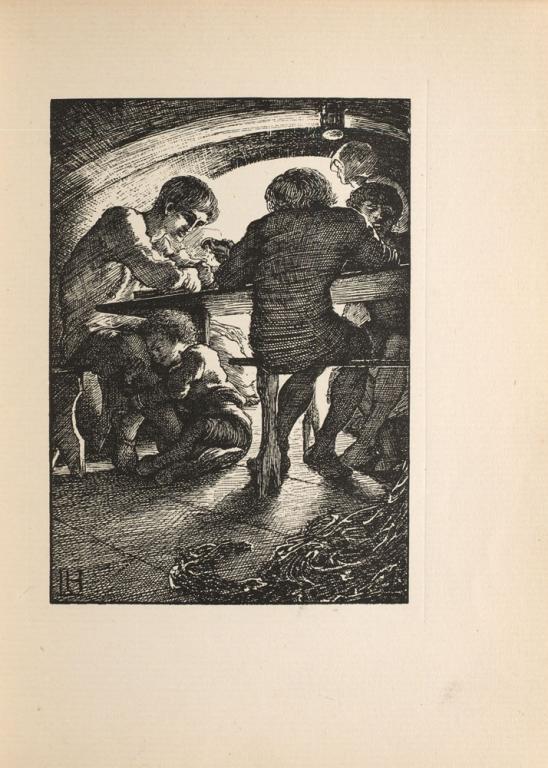

“Rol’s Worship”

In “Rol’s Worship,” wood-engraving processes and technologies are explicitly represented, showcasing Clemence’s ability to frame her craft as a self-referential and expressive medium. The scene depicts three young men sitting at table engraving woodblocks. A wood-engraving tool, likely a spitsticker, is visible in the hand of the young engraver seated in the middle of the table. Another feature to note is that wood is visually dominant in “Rol’s Worship.” The farm hall enclosure is made from wood, including the large arch and panelled flooring, and the table with benches in the foreground is recognizably wooden. Wood is portrayed here as an all-encompassing reality for the craftspeople and even the young boy, Rol, who has nestled himself alongside a wooden table leg.

The various depictions of wood and wood engraving in “Rol’s Worship” can be primarily be understood as Housman making her artistic contributions to the illustration explicit: announcing her identity and value as a craftswoman by overwhelming the visual scene with references to the world of wood-engraving. Additionally, these depictions function as a visual metaphor by portraying craft as a medium for reimagining reality. In this case, wood engraving enabled Housman to imagine and demonstrate a new reality based on her progressive ideologies. By depicting a woman in the workplace alongside men, Housman critiques the gender-segregated classes which she attended at the South London Technical Art School (Natt). Though the value of craft is presented in multiple ways throughout the publication, it is firstly brought to the reader's attention by this bold illustration.

Figure 5. "Rol's Worship," The Were-Wolf, John Lane at The Bodley Head, 1896.

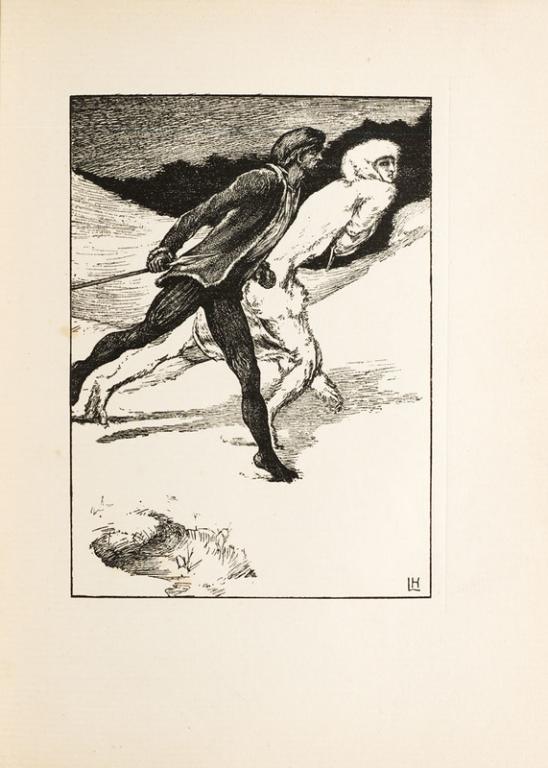

“The Race”

“The Race,” the fourth full-page illustration to The Were-Wolf, depicts Sweyn and White Fell running in matched stride with each other. Though they appear consistent in terms of space, dichotomies emerge when this illustration is examined in the context of the medium which reproduced it. Sweyn is depicted as a dark figure, a shape that stands out against the white snowy landscape that White Fell, depicted as a light figure, seems to blend into. However, this dark and light dichotomy is reversed upon the wood-engraved block. Considering that wood engraving involves carving the “whites out” of an illustration, from Housman’s perspective, it is White Fell who is in artistic focus. Furthermore, it is White Fell, rather than Sweyn, who stands out against the image.

“The Race” subtly reflects the transformative process of wood engraving: highlighting that what may have been the focal point of the illustrator may not have been the focal point of the engraver. This illustration is a true testament to Housman’s ability to reimagine her brother’s designs and reinvent them as new, reformed works in an entirely different medium. Additionally, the dichotomy of illustration and engraving embedded in “The Race” can broadly be understood in terms of the complex gender dichotomies existing in Housman's society at the time of her craftsmanship. The opposing forces working in this illustration are representative of Housman’s attempt to situate the woman as a more prominent figure, equal to a man, in the problematic social environment that she and her fellow female wood engravers were forced to operate within at the end of the 19th century.

Figure 6. "The Race," The Were-Wolf, John Lane at The Bodley Head, 1896.

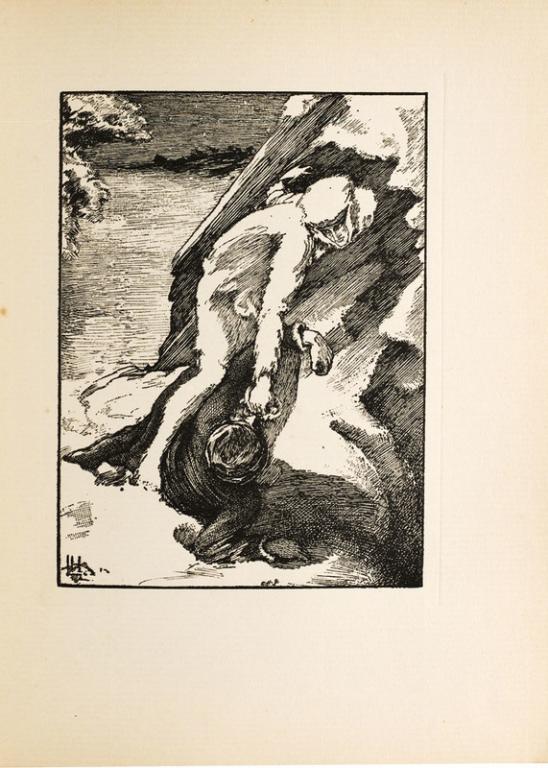

“The Finish”

“The Finish,” the fifth full-page image to The Were-Wolf, calls attention to the methods involved in wood engraving and signifies the importance of the line. Clemence’s engraving technique is very apparent in this illustration: the diagonal graves that create texture and shade dominate the work as much as the contextual action within it. Though these lines enhance the visual effect of the illustration by embedding more detail, they also emphasize its materiality and deliberately reference the process by which it was reproduced. By examining the line, “The Finish” can be understood as a declaration of Housman’s medium and her identity as a craftswoman. Though her credentials are not present anywhere in the illustration, Housman’s mark is left through the evidence of her precise technique. The lines in “The Finish,” and the other illustrations throughout the novella, are careful statements of ownership, of personal influence, and of identity.

Figure 7. "The Finish," The Were-Wolf, John Lane at The Bodley Head, 1896.

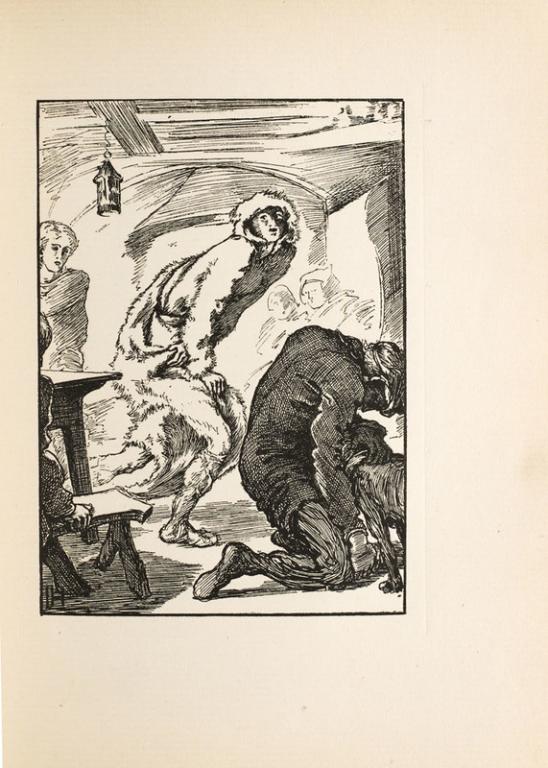

“White Fell's Escape”

This notion is also evident in “White Fell’s Escape,” as Housman’s ideas of feminism and gender are conveyed through her use of the line to emphasize the motion of transformation. Transformation in this image at the contextual level is a transformation from woman to were-wolf, but also represents the transformation that occurs in wood-engraving reproduction: from illustration to engraving to print. The emphasis on transformation in this illustration can also be examined from a feminist persepctive: as an emphasis on the transformation of the traditional Victorian woman into the ‘New Woman.’ Housman’s stress on the symbol of the were-wolf through the use of the line is not only a reference to transformative reproductive processes in wood engraving, but to the transformative state of the woman at the fin-de-siècle.

Figure 8. "White Fell's Escape," The Were-Wolf, John Lane at The Bodley Head, 1896.

Wood Engraving & The Were Wolf (1896)

By examining the context and production of The Were-Wolf’s illustrations, it is evident that Clemence Housman regarded wood engraving as a meditated practice through which she could contemplate the sociopolitical position of women in late-Victorian London and express her ideologies creatively. Housman’s continual representation of wood-engraving throughout the illustrated novella serves to critically assert the value in feminine creativity, feminine agency, and feminine contributions to the Victorian illustrated book industry. Considering that the majority of female wood-engravers’ identities were virtually lost within the process of their craft, there is a substantial need for more research on the part women played in ‘back-room activities’ (Kooistra 280). Using this analysis of Housman’s engravings as a framework for understanding critical making in relation to the expression and reclamation of artistic identity, the contributions of unidentified female wood-engravers from the fin-de-siècle can begin to be rightfully acknowledged.

© Emma Fraschetti, Ryerson University, 2020.

Works Cited

Fraschetti, Emma. “Rol's Worship (1896), by Laurence and Clemence Housman.” COVE Editions, 2020. https://editions.covecollective.org/content/rols-worship-1896-laurence-a....

Fraschetti, Emma. “The City and Guilds South London Technical Art School.” COVE Editions, 2020. https://editions.covecollective.org/place/city-and-guilds-south-london-t....

Fraschetti, Emma. “Wood Engraving Technology Dominates the Victorian Illustrated Book.” COVE Editions, 2020. https://editions.covecollective.org/chronologies/wood-engraving-technolo...

Housman, Clemence. The Were-Wolf. John Lane at The Bodley Head, 1896. COVE Editions, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018, editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/were-wolf-0.

Hunsberger, Emily. “Wood Engraving as an Art and a Trade,” Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Emily Hunsberger, et al. COVE Editions, 2018. https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/wood-engraving-art...

Janzen Kooistra, Lorraine. “Magazine and Book Illustrations for The Were-Wolf.” Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra et al. COVE Editions, 2018. https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/magazine-and-book-...

Janzen Kooistra, Lorraine. “Victorian Women Wood Engravers: The Case of Clemence Housman.” Women, Periodicals and Print Culture in Britain, 1830s-1900s: The Victorian Period, edited by Alexis Easley, Clare Gill, and Beth Rodgers, Edinburgh University Press, 2019.

Khan, Hadia. “Brief Biographies of Clemence and Laurence Housman," Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Hadia Khan, et al. COVE Editions, 2018. https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/brief-biographies-...

Natt, Harpreet Kaur. "Textual History and Contemporary Reception of Clemence Housman's The Were-Wolf.” Clemence Housman's The Were-Wolf, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Harprett Kaur Natt, et al, COVE Editions, 2018. https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/textual-history-an...’s-were-wolf.

“Rol’s Worship.” The Were-Wolf, John Lane at The Bodley Head, illustrated by Laurence Housman and engraved by Clemence Housman, 1896. COVE Editions, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018, editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/were-wolf-0.

Sander, David M. Wood Engraving: An Adventure in Printmaking. Viking Press, 1978.

Stevens, Bethan. “Dalziel Brothers.” Woodpeckings, Sylph Editions, 2016. www.sussex.ac.uk/english/dalziel/discover-the-dalziels/.

Stevens, Bethan. “Wood engraving as ghostwriting: The Dalziel Brothers, losing one's name, and other hazards of the trade.” Textual Practice, vol. 33, no. 4, 2017, pp. 645-677. Taylor & Francis Online,DOI:10.1080/0950236x.2017.1365756.

Smith, Harold L. The British Women’s Suffrage Campaign, 1866-1928. Addison Wesley Longman Ltd, 1998.

“The Finish.” The Were-Wolf, John Lane at The Bodley Head, illustrated by Laurence Housman and engraved by Clemence Housman, 1896. COVE Editions, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018, editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/were-wolf-0.

“The Race.” The Were-Wolf, John Lane at The Bodley Head, illustrated by Laurence Housman and engraved by Clemence Housman, 1896. COVE Editions, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018, editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/were-wolf-0.

Tickner, Lisa. The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign, 1907-1914. University of Chicago Press, 1988.

“White Fell’s Escape.” The Were-Wolf, John Lane at The Bodley Head, illustrated by Laurence Housman and engraved by Clemence Housman, 1896. COVE Editions, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018, editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/were-wolf-0.