Created by Emilka Jansen on Tue, 03/02/2021 - 11:22

Description:

Heinrich Hoffmann’s enduring appeal has established Der Struwwelpeter (1845) as a horrifying didactic text that depicts the cruel consequences of wicked behavior. Born in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, in 1809, Hoffmann conforms to the early ideology of sin that treated children as little sinners. His influential children’s book endures, however, beyond the nineteenth century and is a fascinating example of evolution across language and genre throughout literary history; Der Struwwelpeter began by strictly conforming to didacticism, but over time, has turned on itself and lost its original didactic intention. Parodied by other writers and translated into over thirty-five languages (New York Public Library), Der Struwwelpeter serves as a foundational text for bedtime horrors, political satire and propaganda, and modern comics and film adaptations.

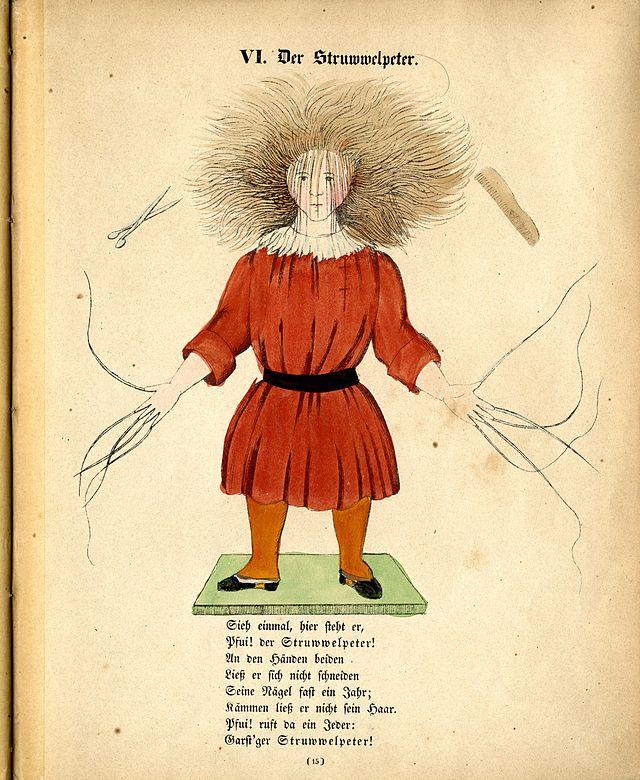

Heinrich Hoffmann, “Struwwelpeter," Der Struwwelpeter, 1845, first edition, Wikipedia.

Hoffmann, a German physician, is best known for writing and illustrating ten rhyming stories about the horrific consequences of disobedience in Der Struwwelpeter. Similar to Lewis Carroll and A. A. Milne who wrote to entertain their young companions, Hoffmann wrote Der Struwwelpeter in 1844 for his three-year-old son, Carl, after failing to find him a suitable Christmas present. Unlike Carroll and Milne, who conform to the doctrine of childhood innocence, Hoffmann strictly upholds didacticism as seen through this plate of Struwwelpeter, or Shock-headed Peter. An unkempt boy with very long hair and nails, he is the first disobedient child to be introduced, and the children’s book is named after him. Struwwelpeter is just the opposite of a model Victorian schoolboy.

Heinrich Hoffmann, “The Dreadful Story about Harriet and the Matches," The English Struwwelpeter, or Pretty Stories and Funny Pictures for Little Children, translated by Alexander Platt, 1848, The British Library.

Three years after the original German publication, Struwwelpeter was translated into English. Possibly rendered by Alexander Platt, the English version became firmly rooted in didactic ideology through its ability to reach a wider audience. The translated tale of “The Dreadful Story about Harriet and the Matches” resonated with early English writers such as Mary Martha Sherwood, whose account of Augusta Noble’s fate in “The Sad Story of a Disobedient Child” bears close resemblance to Harriet’s terrifying encounter with matches. As a result of their disobedience, the children’s dresses catch fire, and both stories end in tragedy. It should be noted that Hoffmann incorporates animals, specifically cats, to warn Harriet of the imminent perils of recklessness; she chooses to ignore their words of caution. Preserving its German didactic roots and effective rhymes, The English Struwwelpeter, or Pretty Stories and Funny Pictures for Little Children was incredibly successful and thus heavily protected under British copyright.

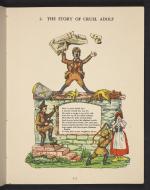

Robert and Philip Spence, “The Story of Cruel Adolf,” Struwwelhitler: A Nazi Story Book by Doktor Schrecklichkeit, 1941, The British Library.

Published by The Daily Sketch in 1941, Robert and Philip Spence's Struwwelhitler—ascribed to Doktor Schrecklichkeit, or Doctor Horror—emerged as a form of anti-Nazi propaganda that backed the British war effort by “rais[ing] money to buy the troops’ radios, games and ‘wollen [sic] comforts,’ as well as supplies for air-raid victims” (The British Library). Instead of Bösen Friederich (Cruel Frederick), the British parody depicts Cruel Adolf committing many of the same atrocities as Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler; they even share the same temperament as seen through this portrayal of Cruel Adolf, who “screamed until his voice was cracked.” In subsequent illustrations, Cruel Adolf is rightfully punished for his actions: he is bitten by his dog Fritz and poisoned to death by the doctor. By replacing naughty children with caricature-like illustrations of renamed political leaders—Adolf Hitler (Cruel Adolf), Benito Mussolini (Little Musso), and Joseph Goebbels (Little Gobby)—Struwwelhitler acquires an element of grim humor that serves as a powerful force against the Nazi regime. Additional parodies include the British Swollen-headed William (1914) and the American Tricky Dick and His Pals (1974). The former satirizes Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany; the latter mocks former President Richard Nixon and his involvement in the 1972 Watergate scandal. As illustrated, the influence of Hoffmann’s Stuwwelpeter allows the children’s book to undergo a remarkable political evolution.

Anonymous, “Der garst’ge Struwelpeter,” printed by C Burckardt, c. 1871-1914, The British Museum.

Turning away from didacticism toward humor and entertainment, Struwwelpeter has paved the way for modern American comics that borrow Hoffmann’s innovative arrangement of text and images. In fact, several editions of Struwwelpeter are housed in the National Art Library’s Comics and Comic Art Collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London—the same collection that holds Rodolphe Töpffer’s L’Histoire Véritable de Monsieur Crépin (1837) and Wilhelm Busch’s Max und Moritz (Victoria and Albert Museum). The former Swiss cartoonist is considered to be the father of the modern comic; the latter German poet is known for his influential pictorial broadsheets. Considering the inclusion of Struwwelpeter alongside these classic precursors of modern comics affirms Hoffmann’s brilliance. In this German comic strip, a misbehaving Struwwelpeter sticks out his tongue, knocks out windowpanes, and pulls the hair of a young girl and the tail of a cat. As punishment, Struwwelpeter contemplates his actions in the last panel, where he sits in a prison cell with his feet in chains. Although the story imposes moralizing lessons, the format of the comic strip suggests that over time, Struwwelpeter has lost its didactic intention and gained an ability to portray humor and horror working in tandem.

Heinrich Hoffmann, “The Story of Little Suck-a-Thumb,” The English Struwwelpeter, or Pretty Stories and Funny Pictures for Little Children (1848), translated by Alexander Platt, ca. 1867, Free Library of Philadelphia.

The didactic qualities of Struwwelpeter are unrecognizable in modern film adaptations. As seen through its last stage of development, Struwwelpeter assumes a complete shift toward humor and entertainment in fantasy romance films such as Tim Burton’s Edward Scissorhands (1990). The titular main character bears a striking resemblance to Hoffmann’s “great, long, red-legg’d scissar-man” but doesn’t commit the same cruel acts. Instead, Edward Scissorhands trims the neighbors’ hedges and grooms their dogs’ hair—activities that speak to his harmless character. Edward Scissorhands, played by Johnny Depp, simply wishes to fit in with society and fall in love; yet, despite his innocence, he shares similarities with Hoffmann’s Scissor-Man from “The Story of Little Suck-a-Thumb.” As seen through this plate, a mischievous young boy, Conrad, faces the consequences of sucking his thumbs: they are cut off by the leaping Scissor-Man. His great chopping shears, in addition to the pooling drops of Conrad’s blood, evoke fear on their own, but Hoffmann adds another layer to this tale through his ghastly account of what transpires: “Snip! Snap! Snip! They go so fast; / That both [Conrad’s] thumbs are off at last.” Hoffmann’s three consecutive exclamation marks capture the urgency and horror of Conrad’s punishment, and the aftermath of this traumatic experience is perhaps even more upsetting: “Conrad stands / And looks quite sad, and shows his hands.” He receives no sympathy from his mother. Arguably the most didactic tale in Struwwelpeter, “The Story of Little Suck-a-Thumb'' is radically transformed by Burton’s portrayal of a kind Edward Scissorhands, leaving viewers to wonder whether the German didactic author would approve of this film adaptation. Hoffmann’s Struwwelpeter clearly remains an unforgettable story for readers around the world.