Created by Aaron Swartz on Mon, 11/01/2021 - 22:22

Description:

At the turn of the Victorian era, manufacturing would experience a boom like none before. A well-running economy and huge technological advantages combined to create a culture that not only produced an unprecedented amount of goods but also had the excess fund to spend on things that weren't a necessity to live. The Victorian obsession with objects combined with other notions of proper culture, such as sex and gender, to create notable differences in the creation and usage of items, dividing them along gendered lines, perhaps none so much as the portable writing desk. Used by Victorian's for writing and safeguarding important objects both at home and on the road, the portable writing desk was gendered in its very creation, but even more so in its use. As we can read in William Makepeace Thackeray's famous novel Vanity Fair, the writing desk became a private place for women to keep aspects of themself hidden from husbands who otherwise controlled their whole lives. Within Thackeray's novel, the writing desk even becomes a seat of power for several of the main characters, particularly Becky Sharp, who uses her desk to secrete information and funds until the contents will enact the dramatic effect she desires. In these ways the portable writing desk is exemplary both of Victorian concepts of material culture, gender, and power.

"A Lady's and a Gentleman's lapdesk,“ from "The Portable Writing Desk — Victorian Laptop," 2010, from the collection of Catherine Golden, Victorian Web.

In this image, we get a closer look at the gendered nature of Victorian culture, down to the most basic material object. On the left, we see a large, square writing desk with a prominent lock and a distinct lack of ornamentation. On the right, we see a much smaller, sloped desk made of papier-mache and painted with a black background and a prominent decorative pattern in the center. Looking between the two objects, the gendered nature is clear. Down to their decoration — and even the very materials they're constructed out of — these desks display the dualistic, gendered thinking of the Victorians. The desk on the left is made from mahogany, an expensive and sturdy wood. Meanwhile, the desk on the right is made from papier-mâché, a much lighter and more delicate material. These objects reflect Victorian conceptions of gender. Women were considered decorative, fragile, and secondary to men, who were to be strong, sturdy, and the primary mover and benefactor of society. Additionally, it's important to note the lock on each desk. The man's desk has a prominent lock on it, showcasing his agency in the world. He could keep secrets, he was allowed a private life, and this was common and accepted societally. The woman's desk — this one at least — has a small lock and a smaller space to keep secret contents.Oftentimes a woman might have no control over any other aspect of her life, being subservient to her father or her husband. Women were not allowed the same rights as men, to keep secrets and have personal lives and beliefs, as these period desks demonstrate.

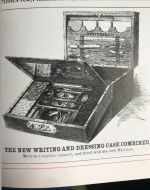

David Harris, "A Writing Desk and Dressing Case Combined, Advertised in a Parkins & Gotto Catalogue of the 1850s," in his Portable Writing Desks, 2008.

In this image, we see an advertisement for a writing desk of the 1850s marketed specifically towards men. The Victorian era was a highly gendered period. Writing a letter with a writing desk could easily be construed as too feminine compared to powerful, masculine activities, such as hunting or gaming. As such, advertisers created objects such as this desk, which contained a dressing-case to make it more marketable towards gentlemen. Additionally, desks marketed towards women were more ornate and light, while male desks were heavier, boxier, and less decorative, as the first image shows. In addition to being a gendered object, this desk provides insight into the crucial role writing desks played in the lives of many Victorian women and men. To quote Jane Austen in a 1798 personal letter, "No part of my property could have been such a prize before, for in my writing-box was all my worldly wealth." This large desk and dressing case offers the gentleman plenty of room for all his valuables.

William Makepeace Thackeray, "Miss Sharp in Her School-Room," in his Vanity Fair, 1848, 1861 woodcut scanned by Gerald Ajam, Victorian Web.

In this image, we see one of the central characters of Thackeray's famous novel Vanity Fair, Miss Rebecca Sharp, using a writing desk. Becky is employed as a governess to look after and instruct the children of a wealthy family, the Crawleys. However, the image demonstrates that she's neglectful of her charges, and her eyes look away to her right as she sits in front of her writing desk. Throughout Thackeray's novel, the writing desk brings together and divides people. For Becky, it acts as a path to the outside world through letter-writing, an important feature of Victorian life. Simultaneously, it allows Becky to have secrets. For Becky, this desk, large for a woman's desk, functioned as a safe keeper of important objects and mementos as well as money and valuables. Her writing desk was a private space, and Becky Sharp hides away a good store of money, jewelry, and other keepsakes in her writing desk to keep them away from her husband, Rawdon Crawley. Becky is a woman who seeks upward mobility in the world and wants more than anything to have power, status, and wealth. She exercises her wish to bend her environment to her will constantly, but her desk is the only place she has to really keep secrets. Within it, she hides more than a thousand pounds, jewelry, and even damning evidence against a now dead acquaintance, George Osborne. Within this privacy, she can act outside of the rigid gender roles of Victorian society. The desk acts as a seat of her power and agency, even though it eventually gets taken from her.

Film clip of "Rawdon Demands Becky Open Her Writing Desk," Vanity Fair (2004), starring Reese Witherspoon and James Purefoy, Granada Pictures.

This image is from a scene in the 2004 movie version of Vanity Fair, produced by Granada Pictures and starring Reese Witherspoon as Becky Sharp and James Purefoy as her husband, Rawdon. This scene takes place at one of the most crucial moments of the novel, when Rawdon returns home from debtor's prison to find Lord Steyne with his wife, though it's unclear just how damning her position is. Rawdon throws Steyne out of his home and forces Becky to hand over all of her keys, including the one to her writing desk. Within it he finds her secrets, the money she's been hiding from him, and the jewels her admirers have bought for her. This scene acts as a crucial reminder of the power at play within Victorian conceptions of gender. Becky is able to find privacy and power within her writing desk, but it's a hollow illusion. In reality, Rawdon has the full right and ability to open her desk and see anything and everything she is hiding from him. He has all the power in their relationship. Interestingly, the movie differs in its depiction from the novel. Whereas Thackeray has Rawdon demand Becky's keys and opens the desk himself, in the movie Rawdon forces Becky to open it for him. The movie's depiction lends itself well to the reality of the Victorian experience, where the woman might hold the keys but the man was in charge of when and how they were used.