"Slumming" in the East End

In the late Victorian era London's East End became a popular destination for slumming, a new phenomenon which emerged in the 1880s on an unprecedented scale. For some slumming was a peculiar form of tourism motivated by curiosity, excitement and thrill, others were motivated by moral, religious and altruistic reasons. The economic, social and cultural deprivation of slum dwellers attracted in the second half of the nineteenth century the attention of various groups of the middle- and upper-classes, which included philanthropists, religious missionaries, charity workers, social investigators, writers, and also rich people seeking disrespectable amusements. As early as in 1884, The New York Times published an article about slumming which spread from London to New York.

Slumming commenced in London […] with a curiosity to see the sights, and when it became fashionable to go 'slumming' ladies and gentlemen were induced to don common clothes and go out in the highways and byways to see people of whom they had heard, but of whom they were as ignorant as if they were inhabitants of a strange country. [September 14, 1884 ]

In the 1880s and 1890s a great number of middle- and upper-class women and men were involved in charity and social work, particularly in the East End slums. The national press covered widely shocking and sensational news from the slums. Anxiety and curiosity about slums could be heard in many public debates to that extent that, as Seth Koven writes:

By the 1890s, London guidebooks such as the Baedeker’s not only directed visitors to shops, monuments, and churches but also mapped excursions to world renowned philanthropic institutions located in notorious slum districts such as Whitechapel and Shoreditch. [1]

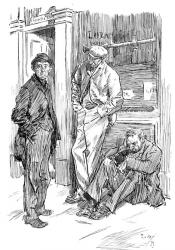

In fact, for a considerable number of Victorian gentlemen and ladies slumming was a form of illicit urban tourism. They visited the most deprived streets of the East End in pursuit of the 'guilty pleasures' associated with the immoral slum dwellers. Upper-class slummers sometimes spent in disguise a night or more in poor boarding houses seeking to experience taboo intimacies with the members of the lower classes. Their cross-class sexual fellowships contributed to diminishing class barriers and reshaping gender relations at the turn of the nineteenth century.

However, slumming was not only limited to odd amusement. In the last two decades of the Victorian era a rising number of missionaries, social relief workers and investigators, politicians, journalists and fiction writers as well as middle-class ‘do-gooders’ and philanthropists made frequent visits to the East End slums to see how the poor lived. A number of gentlemen and lady slummers decided to take up temporary residence in the East End in order to collect data on the nature and extent of poverty and deprivation. Some slummers were disguised in underclass drags in order to transgress class boundaries and mix freely with the poverty stricken inhabitants of the slums. Written or oral accounts of their first-hand observations arose public conscience and motivation to provide slum welfare programmes, and prompted political demands for slum reform.

The last two decades of the nineteenth century witnessed the upsurge of public inquiry into the causes and extent of poverty in Britain. Some of the most outstanding late Victorian slummers were Princess Alice of Hesse, the third child of Queen Victoria; Lord Salisbury, and his sons, William and Hugh, who resided temporarily in Oxford House, Bethnal Green; William Gladstone, and his daughter Helen, who lived in the south London slums as head of the Women's University Settlement. (Koven 10) Even Queen Victoria visited the East End to open the People’s Palace in Mile End Road in 1887.

Benevolent middle- and upper-class women went to slums for a variety of purposes. They volunteered in parish charities, worked as nurses and teachers and some of them conducted sociological studies. Such women as Annie Besant, Lady Constance Battersea, Helen Bosanquet, Clara Collet, Emma Cons, Octavia Hill, Margaret Harkness, Beatrice Potter (Webb), and Ella Pycroft explored some of London’s most notorious rookeries, and their eye-witness reports gradually changed the public opinion about the causes of poverty and squalor. By the turn of the nineteenth century thousands of men and women were involved in social work and philanthropy in London slums.