Created by Emilka Jansen on Tue, 10/18/2022 - 11:25

Description:

Needlework, the art or practice of sewing or embroidery, plays an important role in the lives of the Brontë sisters and their novels. A quiet Victorian pastime for young women, needlework engrossed women in their work mending clothes and decorating elegant fabrics. This essential feminine skill was a key component of a woman’s education that solidified her position in the home and allowed women to fulfill their domestic responsibilities as mothers and wives. Generally understood in two categories, needlework simultaneously encapsulates the plain, mundane work that women sewed, and the more refined, decorative art of embroidery. Both forms allow us to stitch together pieces of the Brontës’ lives to examine how needlework turns domestic art into a subversive practice that often challenges conventional notions of femininity.

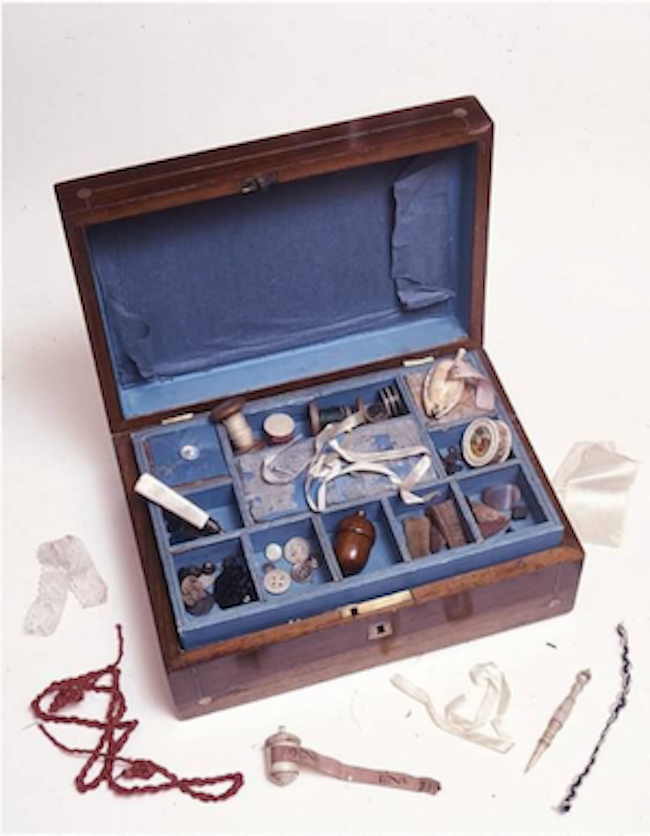

Sewing box, 252 x 173 x 95mm, Brontë Parsonage Museum.

Made of rosewood, mother of pearl, and metal, Charlotte Brontë’s sewing box contains several compartments full of tools that she would have used to sew and embroider material. The open hinged lid gives way to buttons, lace, ribbons, and braids, as well as different kinds of sewing equipment: pins, needles, and metal hooks and fastenings can be found in this full yet organized sewing box that allowed Charlotte to store her supplies in one place. Much like a writing box that would contain paper, pen, and ink, a sewing box holds all necessary equipment to complete a sewing project.

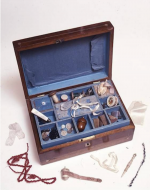

Charlotte Brontë, stitching sampler, linen on wood, 365 x 245mm, 1828, Brontë Parsonage Museum.

As Deborah Lutz asserts in her introduction to The Brontë Cabinet: The Lives in Nine Objects, Victorians recognized the ways that “ordinary objects can carry us to other times and places” (xxi); objects hold agency and convey stories about the past that inform the present and future. While viewers today might easily overlook a scrap of cloth like the one depicted above, this sampler highlights Charlotte Brontë's meticulous work, inviting us to “read” her sewing as an entryway into the social conventions informing nineteenth-century needlework. Featuring texts from the Bible enclosed in a continuous decorative border, Charlotte’s stitching reveals the importance of needlework and religion in the sisters’ lives. The sisters spent countless hours studying the Bible and perfecting their embroidered alphabet. These samplers, or personal references of a seamstress’s work, held immense value in the Victorian era and may be compared to writing samples today.

Charlotte Brontë’s Dress, c. 1854, from Jacqueline Hyman, The Restoration Studio.

Needlework played an important role not only in Charlotte Brontë’s childhood, when she was learning to make stitching samplers, but also in her adult life as she dressed to properly present herself to the public. Shortly after her marriage to Arthur Bell Nicholls in 1854, Charlotte became pregnant. She wore this going-away outfit, seen in full in the top right-hand corner of this image, on her honeymoon to County Clare, Ireland. Consisting of a bodice and a skirt, this dress brings attention to the bodice’s open stitch holes, where the seams have intentionally been removed to accommodate Charlotte’s pregnant stomach. In addition, textile conservator Jacqueline Hyman notes that “the fastening hooks around the skirt waist were altered to increase the waist size by about 3/8 of an inch” (University of Victoria Libraries). These adjustments, as well as the fabric’s worn, distressed appearance, offer material insight into Charlotte’s tragic pregnancy and allow contemporary audiences to put together the story behind the missing stitches of Charlotte’s dress.

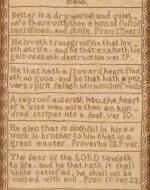

F. H. Townsend, "It removed my veil from its gaunt head, rent it in two parts, and flinging both on the floor, trampled on them," from Jane Eyre (1847), by Charlotte Brontë, 1897 edition.

This image illustrates the key scene in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre when the titular character dreams that Bertha, the “madwoman in the attic,” tears Jane’s wedding veil. Emblems of modesty, veils would have served an important purpose as they signaled social class and status during the Victorian era, yet Jane diminishes its value when she says to Mr. Rochester, “I thought I would carry down to you the square of embroidered blond I had myself prepared as a covering for my low-born head.” In another instance, Jane refers to the veil as “the plain square of blond” (emphasis added), suggesting to readers its mundane simplicity. Yet, Jane also brings attention to this material object that she makes with her own hands: sewing such a veil would have required time and meticulous craftsmanship. When Bertha shreds the veil into pieces and tramples it, she commits an act of destruction that not only ruins Jane's work but also subverts marriage as an institution.

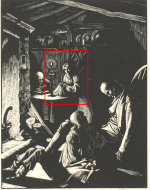

Clare Leighton, "Death of Earnshaw," Wuthering Heights (1847), by Emily Brontë, 1931 Random House edition, The British Library.

Charlotte was not the only Brontë sister to feature needlework in her fiction. In Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847), Ellen “Nelly” Dean spends ample time simultaneously narrating the story and engaging in needlework. Before beginning her frame narrative to Mr. Lockwood, the new tenant at Thrushcross Grange, Nelly says, “I’ll just fetch a little sewing, and then I’ll sit as long as you please.” Just twenty pages later, “the housekeeper rose, and proceeded to lay aside her sewing.” Sewing and storytelling, in turn, become deeply entwined, suggesting that this quiet pastime gives voice to Nelly’s narrative. Needlework flanks the narrative, allowing Nelly to concentrate on the story she presents, especially in this scene that shows Nelly and her needlework presiding over Mr. Earnshaw’s death. The narrator lurks in the background of the image, beside a candle that lights the dark interior and allows Nelly to focus on her stitching. Yet, her work as a housekeeper can also be read as a distraction. Nelly is an unreliable narrator who likely drops several stitches as she distorts the story by inserting her own biases and revealing her close connection to other characters in the novel.

The Brontë Sisters, “Brontës writing in the rectory at Haworth, in Yorkshire, England," engraving after a watercolor, c. 1800s, Granger/Bridgeman Images.

As others have suggested throughout this gallery exhibit, scholars have previously mistaken the Brontë sisters for each other. This image, read from left to right, depicts Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë engrossed in various creative endeavors, including reading, writing, and sewing. At the center of this engraving, Emily sits hunched over a piece of fabric that she holds in between her hands. The position of her hovering right hand, in particular, suggests she is about to poke a hole in the material that she embroiders. But what is she making? Shrouded in draping fabric and ruffles, Emily leaves viewers wondering whether she is mending clothes or decorating an elegant textile. Although Emily’s Wuthering Heights has fewer references to needlework when compared to her sisters’ works, her interest in embroidery is fitting considering that she was the most reclusive of the three sisters. Yet this image also suggests that needlework was not necessarily a solitary activity. Surrounded by Charlotte and Anne as they read and write, Emily joins in on this collective artistic pursuit with her sisters by her side. Together, the Brontës form a literary trio of female writers whose focus on the arts, including needlework, respectively informs their novels.