The Textual and Publication History of the Picture of Dorian Gray, its Preface, and Controversy

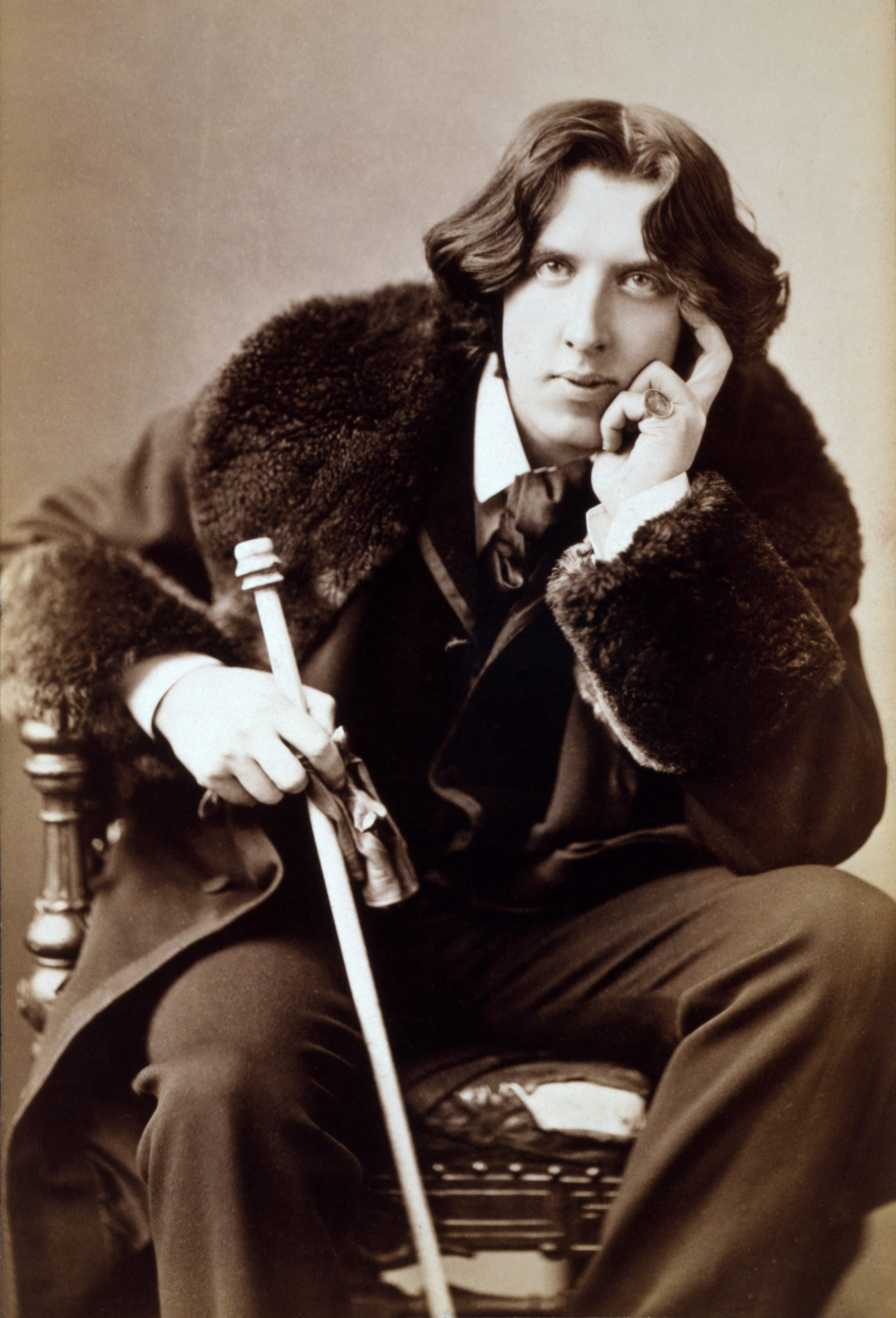

From the very beginning of its publication, Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray was met with incredible controversy due to the text’s allusions to homoeroticism, then deemed as immoral and indecent behavior. The controversy of the book’s content fueled a complicated textual history as well as the text’s publication. The original 1890 text was published as a novella in an American-run magazine titled, Lippincott’s. The magazine’s editor, J.M. Stoddart, began seeking a larger audience for the publication in the mid-1880s, due largely to the failing “family-friendly” middle-class readership (Beasley 3). Stoddart met with authors such as Wilde and Arthur Conan Doyle in 1889, negotiating a publication deal for both English and American distribution. The magazine editor made several revisions to Wilde’s 1890 text--without notifying the author-- finding the novel’s “suggestive elements to be unacceptable reading for his magazine’s audience” (Beasley 1). Even after Stoddart’s revisions, there remained a scathing controversy with Dorian Gray and much of the reading public. Wilde responded to one review by stating, “Each man sees his own sin in Dorian Gray. What Dorian Gray’s sins are no one knows. He who finds them has brought them.” Wilde’s comments demonstrate the author’s active interpretative exercise and defense against his reading public’s detractors. As a result, Wilde made several revisions of his own to the 1891 version that was published by Ward, Lock, and Company (Beasley 8). Scholar Maddison McGann observes how “[i]t should come as no surprise … that the 1891 edition of Dorian Gray was substantially altered, expanded, and redacted to include point reflections on influence, aesthetics, and that the unrefined, “literary public of England” who had no sense “for anything except newspapers, primer, and encyclopedias” (McGann 604). As McGann notes, the public reception of Wilde’s 1890 novella resulted in the author expanding and revising the text, as well as adding the Preface to its 1891 version.

In the Preface, Wilde presents a defense of his art and his station as an artist. He states the artist’s aim is to “reveal art,” “conceal the artist,” all the while remaining as “the creator of beautiful things.” He later invokes the character of Caliban from William Shakespeare’s The Tempest and relates him to the nineteenth century’s dislike of both realism and romanticism. Wilde identifies a dialogue of contrasts present in this aspect of the Victorian Mood by comparing both cultural characteristics of his temporal context with the “rage” of one of Shakespeare’s most notable “monsters.” In addition to being a literary reference, the word “Caliban” is defined by the OED as a “man of degraded bestial nature.” This invokes a sense of irony due to the nature of Wilde’s 1895 indecency trial. In essence, he ascribes the same kind of characteristic to his own time and place as what he would be personally accused of four years after Dorian Gray’s second publication. Dorian Gray’s Preface stands as the response to the text’s original 1890 public controversy. The Preface also acts as a foreshadowing to Wilde’s 1895 public trial where the author was forced to engage in both a defense of himself as an Artist as well as participate in the interpretative conversation about his work.

Additional Reading

--Beasley, Brett. “The Triptych of Dorian Gray (1890–91): Reading Wilde’s Novel as Three Print Objects.” Cahiers Victoriens & Édouardiens, vol. 84, no. 84 Automne, 2017, pp. 18–18, https://doi.org/10.4000/cve.2978.

--Grolleau, Charles. The Trial of Oscar Wilde, from the Shorthand Reports. Project Gutenberg.

--McGann, Maddison. “Reading Reception in Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 54, no. 4, 2021, pp. 604–24, https://doi.org/10.1353/VPR.2021.0046.