Created by Charlotte Mahn on Thu, 11/09/2023 - 15:49

Description:

Jane Austen's Mansfield Park (1814) is perhaps the author's least popular novel. It is often left off of syllabi, and that may partly be due to its protagonist. Fanny Price is a shy and quiet girl who very rarely demonstrates the kind of outgoing nature that accompanies many of Austen's other heroines. The letter that Fanny writes to her friend Mary Crawford, though, shows a woman standing up for herself and her decision not to marry a man whom she loathes. It also demonstrates the kind of wit a reader of any time or era would enjoy, and with it brings an economic context to Austen's time. This case examines what it takes to write a letter in the Regency era and how Fanny Price connects to the world of Jane Austen, both the world she lived in and the worlds she created. The first two images showcase the process of Regency-style letter writing, the third image demonstrates the practice of "franking" a letter, and the fourth image puts Fanny Price side by side to Charlotte Lucas, a character from Austen's Pride and Prejudice who chooses the opposite path--she does not marry for love.

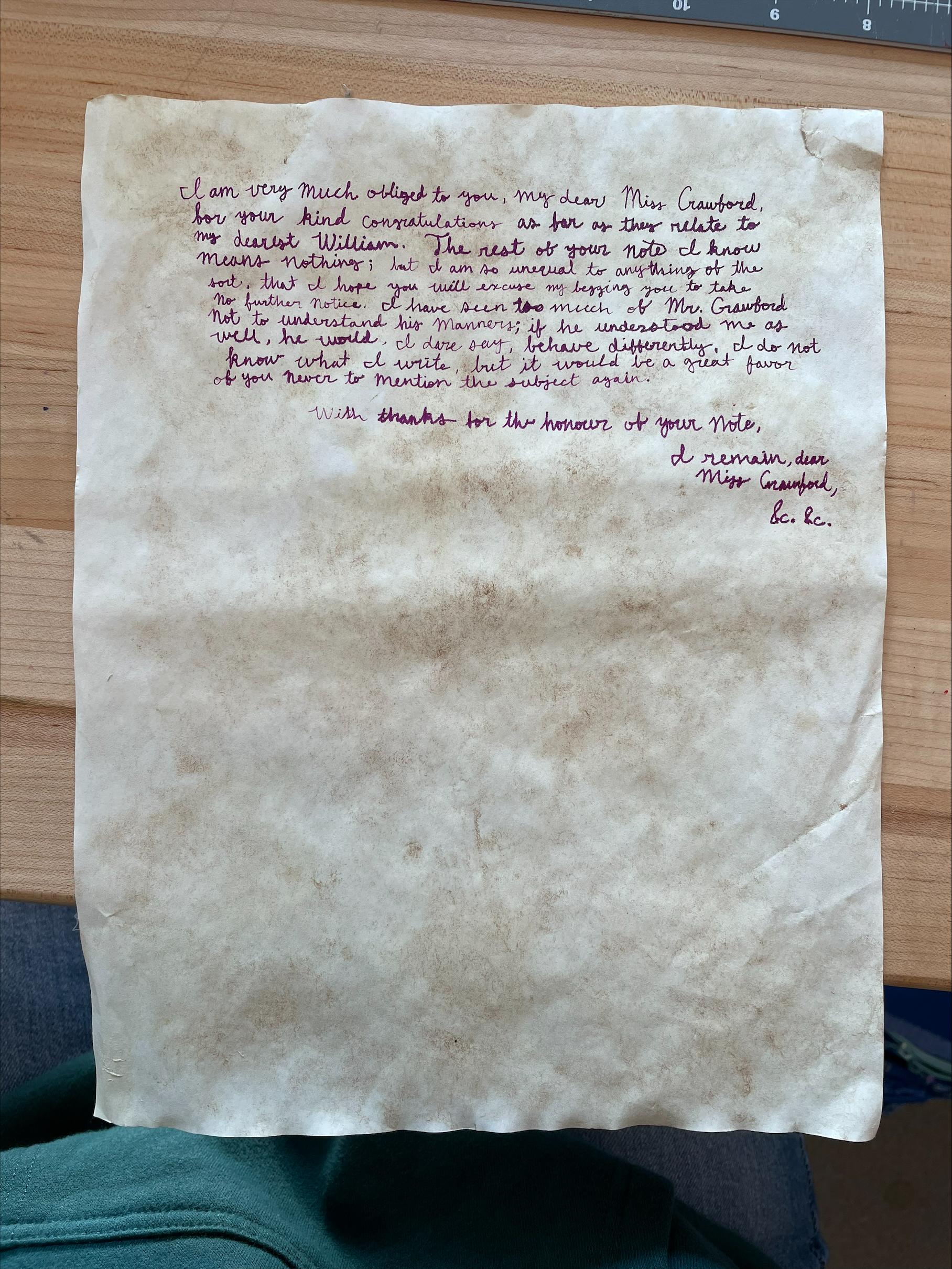

Recreation of Fanny Price's Letter to Mary Crawford, Volume II, Chapter XII, Mansfield Park (1814), by Jane Austen, crafted by Charlotte Mahn, 2023. This image shows the short letter on paper that has gained an antique-look through staining by tea bags. A classmate brought in this stained paper for the entire class, a very thoughtful gift for those trying to recreate the Regency-era letter. The dip pen was a clear spiral design that looked dipped in blood when I lifted it from the small bottle of ink. The letter was later folded and sealed with wax. Franny Price is a timid creature, and I imagine her almost crouching when she speaks to figures of authority in her life; thus, I wrote in smaller writing than I normally would have to embody someone who has little confidence. There is plenty of space left on the page once Fanny is done with her short response to Mary Crawford.

Composing Franny Price's Letter Using a Dip Pen and Purple Ink, from the IdeaLab at Skidmore College, crafted by Charlotte Mahn, 2023. This image shows the scrap piece of paper I used to practice my letter writing before committing to the tea-stained piece of paper shown in the first image. Before doing this project, I had never used a dip pen nor had I recently written in cursive, so I decided that I should practice before I officially try to recreate Fanny's letter. At the top, I began to write the letter to understand just how far one pen dip in ink would take me. I then wrote the cursive letter to practice those letters and motions and also refer back to because I did not remember all of them. I wrote a few words to practice with different amounts of ink on the pen, and at one point I realized a significant amount of ink got onto the side of my finger, which explains the large smudge toward the bottom of this paper. The process of writing this letter led me to understand how much of a skill this must have been in that era and why its practice was emphasized. This was a short letter, and yet my hand began to grow tired from the delicate and precise movements I was making so as to not smudge the paper.

Recreation of Fanny Price's Franked Letter to Mary Crawford's Address, Mansfield Park (1814), by Jane Austen, crafted by Charlotte Mahn, 2023. Seen here is what the outside of Fanny Price's letter to Miss Crawford would have looked like. Because Fanny and Mary lived in the same area, one did not have to be too specific with numbered addresses; thus, "The Parsonage" and Mary Crawford's name are suitable for the postman to find the home to deliver the message. What is interesting about this letter, though, is that "Sir Thomas Bertram" is written at the bottom. At this time, letters cost money to receive unless one was a member of Parliament or royalty. As Franny was staying with her uncle, a member of Parliament, she could "frank" a letter and send it for free by simply having his name signed at the bottom of the letter's folded outside address. To save money on envelopes, letters of this time were often folded. This letter folds the sheet into three, then rotates the letter 90 degrees, and folds the letter into thirds again, tucking the bottom into the top. On the back is sealing wax and a stamp to seal the letter.

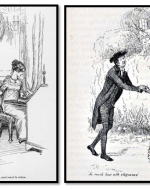

Hugh Thomson, "The note was held out, and must be taken," 1897, for Mansfield Park (1814), Volume II, Chapter XII and "So much love and eloquence," 1894, for Pride and Prejudice (1813), Volume I, Chapter XXII. I chose these images from Hugh Thomson's illustrations of Jane Austen's novels to highlight the similarity and differences between Fanny Price in Mansfield Park and Charlotte Lucas in Pride and Prejudice. Charlotte and Fanny come from similar backgrounds: large families with no clear future as they are impoverished gentility. Charlotte does not marry for love but for practicality. And Charlotte's best friend, Elizabeth Bennet, is shocked by this decision. Elizabeth believes everyone should marry for love, but that is not a practical option for Charlotte. Fanny Price on the other hand wants to marry for love, and her friend, Mary Crawford, is shocked that Fanny does not want such a practical marriage to her brother, Henry. Just before writing this letter to Mary Crawford, the shy protagonist of Mansfield Park denies Henry Crawford's hand in marriage, though with his hand he offers stability and the chance for Fanny to escape her destitute life in Portsmouth. Henry Crawford, as Fanny already knows, is later found out to be a scoundrel. Not many people give Fanny her flowers for her courage to deny a life with someone so obviously affectionate for her. But perhaps Fanny is not immediately deserving of these flowers as she was living with her uncle at the time, gaining a proper education and her chances for marriage then became much better than the twenty-seven year-old Charlotte Lucas. These two images, side-by-side, really capture their relationship with these men they feel no affection for; Charlotte (pictured on the left) makes her primary concern the future of her family while Fannt (pictured on the right) chooses to wait for love. Austen finds ways to make the reader consider the economic consequences of marriage throughout her oeuvre, including this comparison between two characters so similar yet so different.