Created by Madison Yurich on Sun, 03/17/2024 - 15:31

Description:

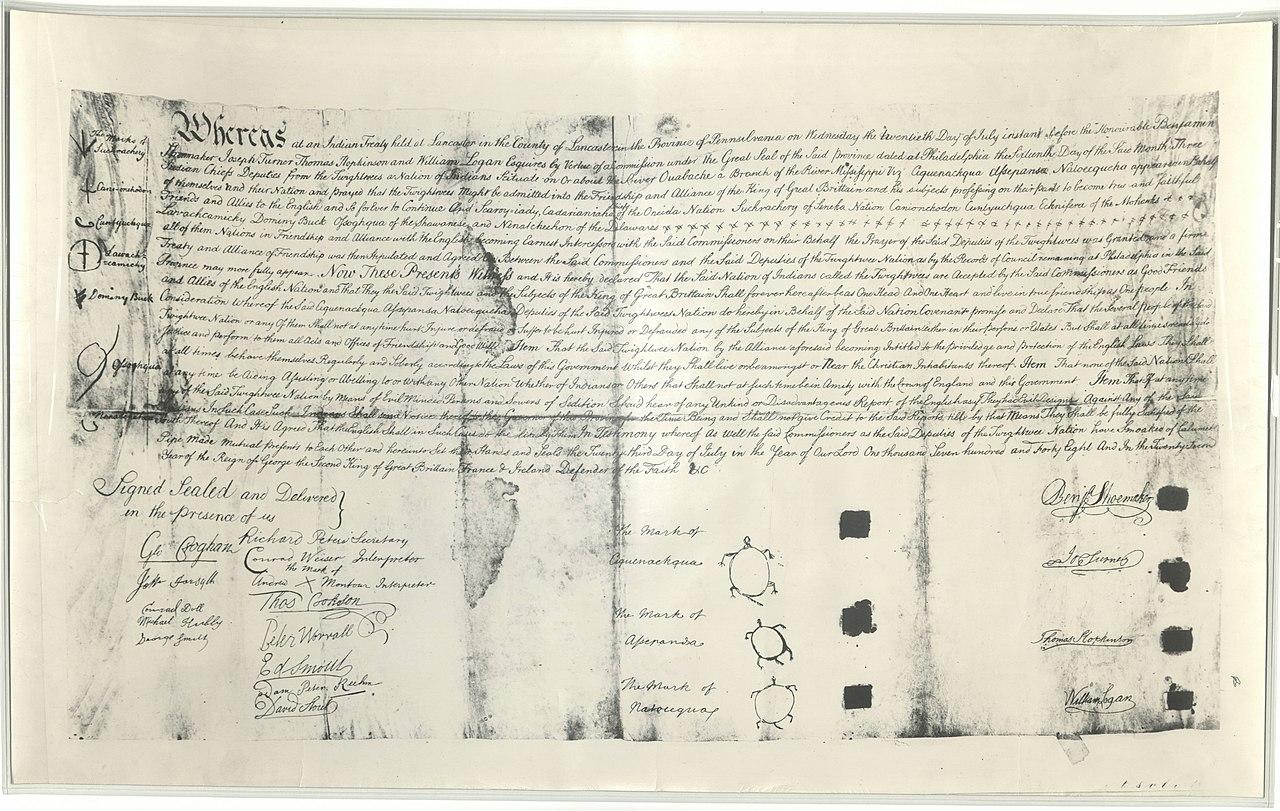

Displayed is an image of the 1748 Treaty of Lancaster, whose signing was influenced by Canassatego's Speech at Lancaster. During his speech, this Onondaga Indian went in front of the Governor of Maryland, and other colonial government officials, to ask for compensation for the land that the Iroquois Indians claimed after defeating the Susquehanna Indians ("Canassatego"). As previously stated, the testimony given within his speech also played a role in what would be the Lancaster Treaty proceedings of 1744, which would establish a boundary between Native American and colonial lands (“Six Nations”). The issue at hand was that the government insisted that they had previously purchased the land from the Susquehannas, so they were reluctant to accept Canassatego's claims. Despite their reluctance, Canassatego aimed to assert the priority of indigenous claims over those of the British (Starna 431). Canassatego began his speech by saying, “Brother, the Governor of Maryland, when you mentioned the Affair of the Land Yesterday, you went back to old times, and told us, you had been in Possession of the Province of Maryland above One Hundred Years; but what is One Hundred Years in Comparison of the Length of Time since our Claim began since we came out of this Ground?” (Levine 476). This line is very important because even though he is questioning the integrity of the deal that his people had with the government, he is still addressing the Governor of Maryland with immense respect and dignity as he refers to him as “brother.” This shows that he thinks highly of him and that he believes that they will be able to come to an agreement about the matter at hand. Regardless of his frustration, he still remains, patient, respectful, and genuine in his concerns, some might argue that this is unlike how the British would speak to and about many Native Americans. Towards the end us his speech, Canassatego states, “We have had your Deeds interpreted to us, and we acknowledge them to be good and valid, and that the Conestogoe or Sasquahannah Indians had a Right to sell those Lands to you, for they were then theirs; but since that Time we have conquered them…” (Levine 478). This line, again, emphasizes the immense respect that the Native Americans have for these white men, and for everyone they encounter overall. In this line, Canassatego shows the trust that he has for these government officials by acknowledging the validity of the deed, but he makes his argument when he says that the lands mentioned in the deed are now owned by his people. Therefore, he does not present a one-sided argument, he acknowledges both perspectives on the matter and explains why he believes a mistake could have been made. While he does approach the situation with timidness at first, he blatantly expresses what he knows to be true which is that the land in question now belongs to his people. Overall, the poise that he possesses when addressing such a heated matter is quite impressive and should be respected when looking back on this historical event.

Works Cited

Canasatego Forgotten Founding Father - Book of Mormon Evidence, bookofmormonevidence.org/canasatego-forgotten-founding-father/. Accessed 17 Mar. 2024.

Levine, Robert S., et al. The Norton Anthology of American Literature. Ninth ed., vol. 1, W.W. Norton & Company, 2022.

“Six Nations Land Cessions.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 9 Feb. 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Six_Nations_land_cessions#/media/File:Twightwee_treaty_of_Lancaster_-_DPLA_-_a7eba5170b87fbfb63c0e75a4eb6f2e2_(page_2).jpg.

Starna, William A., and George R. Hamell. “History and the Burden of Proof: The Case of Iroquois Influence on the U.S. Constitution.” New York History, vol. 77, no. 4, 1996, pp. 427–52. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23182553. Accessed 17 Mar. 2024.