Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857

The passage of The Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857 is often seen as an indisputable milestone for women’s rights. The act was the first piece of legislation passed by Parliament that made “divorce legal under British law and was the first law to protect a wife’s property” (Kelly). This act was significant in the fight for women’s rights because women were no longer able to be seen merely as their husband’s slave, but as an individual with legitimate rights. Women were granted political power with the passing of this act by having the ability to escape mistreatment and abuse executed by their husbands without the fear of losing their future property and possessions after their agenda was completed. Although divorce was illegal unless specially granted by an act of Parliament prior to its enactment, the legislation was the second law to address the ramifications of divorce on women after the 1839 Custody of Infants Act (Kelly). The act protected women with an array of marital statuses, including “divorced, separated, and deserted wives” (Kelly).

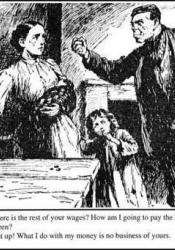

Prior to the passage of the act, “the only chance one had to receive a divorce was through a Private Act of Parliament” (Kelly). The act greatly increased womens’ opportunity to receive a divorce. “Between 1670 and 1857, 379 Parliamentary divorces were requested and 324 were granted. Of those 379 requests, eight were by wives, and only four of those were granted” (Kelly). Society placed many obstacles in the path of women attempting to request a marriage dissolution. Requesting a dissolution of marriage from Parliament required a large sum of money, the ability to travel to London, and an acceptable cause of release from the matrimony. The high cost of requesting a divorce decree from Parliament worked against women’s favor, due men wielding financial control of the family. Only aristocratic women were able to initiate divorce processes since they did not depend on their husband’s money (Layton and Landow). Secondly, one had to stay in London for the duration of their case, which further alienated groups of women whose residence was too far to make the trip. Many women were unable to file for a divorce because they were not able to leave their children for such an extended amount of time, since the process “took the form of a three-stage process that occupied a decade” (Layton and Landow). Lastly, women had to prove their husband committed “aggravated adultery, which is adultery ‘aggravated’ by bigamy, incest, bestiality, sodomy, desertion, cruelty, or rape” (Kelly). If the woman was unable to obtain concrete evidence of her husband’s actions, she would be denied the divorce since aggravated adultery was the only justifiable cause of her divorce. These obstacles disallowed many women the opportunity to escape her marital imprisonment.

The sexist double standard of the Victorian era was prevalent by the Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857’s passage having little effect on men’s opportunity to obtain a divorce. Of the many divorces requested from Parliament prior to 1857, almost all made by men were granted. Unlike women, men did not have to obtain evidence against his wife. Men who desired a divorce simply had to state in his request to Parliament that he “was a victim of his wife’s adultery” (Kelly). Society believed that a wife’s infidelity was more destructive to the family since “titles, land, and wealth passed to the oldest male heir — it was absolutely essential that the heir be the actual son of the father who possessed the title” (Layton and Landow). Women underwent greater scrutiny in this regard because their disloyalty had the opportunity to disrupt the succession of wealth in their family, while the infidelity of men did not. Male divorcees’ names went untarnished if he was the one who was “mistreated.” Female divorcees understood their estrangement came at “the cost of reputation and status,” (Kelly), no matter the cause, since divorces were considered to tarnish a woman’s value.

The Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857 changed the dynamic of women’s rights and family law. Due to the emerging equity in the potential for both spouses to obtain and divorce, the responsibilities of both spouses were redefined. Men began to place more importance on their wives and began to dismiss sexist notions such as the belief that “no man should so much as bow without first being acknowledged by a woman” (Cocks). Marriage began to be viewed as a partnership, and not a dictatorship. Many couples began to realize it was beneficial to both parties to retain their families and avoid undergoing the process of a divorce.

Additionally, the rights of middle and lower class women were also recognized by the act’s passage by its “establishment of a cheaper one-court system” (Kelly). The financial availability of divorce caused middle and lower class men to put more effort in maintaining a stable household (Cocks). Men of lower financial status wanted to keep their families together because they would not be able to afford the spousal support required by law to be given to their wives if they were to be granted a divorce (Cocks). The passage of the Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857 gave women the opportunity to be their own agents of change if they were unhappily married.

Works Cited:

Cocks, Harry. “The Cost of Marriage and the Matrimonial Agency in Late Victorian Britain.” Social History, vol. 38, no. 1, Feb. 2013, pp. 66–88. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1080/03071022.2012.759774.

Hager, Kelly. "Chipping Away at Coveture: The Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857." BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romaniticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. 18 September 2020.

Layton, C., & Landow, G. P. (n.d.). The Origins of Victorian Divorce Law. Retrieved September19, 2020, from http://www.victorianweb.org/gender/layton2.html