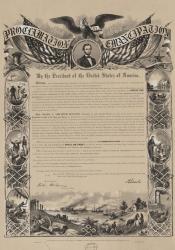

Emancipation Proclamation (1862-1863)

In September of 1862 Preisdent Abraham Lincoln gave the Executive Order that of January 1, 1863 that all slaves being captive in the United States is a practice of rebellion and therefore shall be forever free. Although this did not change the status of most of the 3.5 million slaves in the south, it did change the presecpective of the war. This Proclamation did not apply to the border states that were still loyal to the union, but shifted the concept of the war from preserving the orginal values of the Union to abolition agaist slavery and the future of a new America.

Lincoln persoally hated slavery and felt it was a moral issue, and was already working towards gradual emancipation in those border states that were left out of the proclamation. This Emancipation had a lot of symbolic effect behind it such as countries like France and England denounced the Confederacy for supporting slavery. As the Union army started to take back control of the south these slaves were slowly freed and emancipated. This also allowed congress to push for the Militia Act which allowed men of color to serve in the military; which ended up adding a total of 200,000 soldiers by the time the war ended. The Confiscation Act was also adopted which allowed slaves siezed by the Union army to be given their freedom and declared forever free. This time line was key for the Union to gain momentum in the war and lead the country to the 13th Amendment.

History.com Editors. “Emancipation Proclamation.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 29 Oct. 2009, www.history.com/topics/american-civil-war/emancipation-proclamation.

“Emancipation Proclamation.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 28 Sept. 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emancipation_Proclamation.

“Emancipation Proclamation Text.” HistoryNet, www.historynet.com/emancipation-proclamation-text.