Fort Wagner: Morris Island, South Carolina

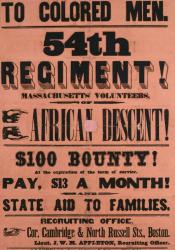

During the American Civil War, there were two Union attacks on a Confederate fort in South Carolina. Both resulted in Union defeat, however, the second attack made by a colored regiment proved these colored soldiers brave and capable of fighting in the war alongside white men. The 54th Massachusetts Infantry, one of the first all-black volunteer Union regiments, made a second Assault on Fort Wagner that took place July 18, 1863. Although it was a disastrous and costly Union defeat, it was the fourth time in the Civil War that black troops played a crucial role. This second Union attack on Fort Wagner encouraged other black men to enlist in the war and fight for their freedom.

Led by Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, these men fought valiantly in effort to capture Fort Wagner. Fort Wagner was located on the south bay of Morris Island in South Carolina, and it wasn’t an ideal location for an attack. A high earth and walls of sand protected Confederate artillery, making it difficult to get to. Before going into battle, Shaw had told his soldiers that he knew they would “prove themselves as men”. It was disastrous; there were 246 Union casualties, compared to 36 Confederate casualties, as well as many Union soldiers left wounded, missing, or captured. While storming the fort, Shaw himself was shot and killed. As a way to dishonor Shaw, Confederate officers buried him at the bottom of a pit with his colored troops who had also died in action. Some of the officers had said, “We have buried him with his n*****s”. Shaw’s family decided to leave his body with his men, and instead of appearing dishonored, Shaw became honored among those in the North.

The Assault on Fort Wagner offered the soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry the chance to prove that they could fight just as well as any white man and that they were willing to die for their freedom. After this battle in South Carolina, Northern newspapers praised Colonel Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts Infantry. They recognized the courageous efforts of colored troops in their fight for their freedom, concluding that they could fight just as bravely as white men. Black enlistments skyrocketed after this battle. By the end of 1863, there were thirty all-black regiments for the Union. Fighting for their freedom allowed these men to feel as though they were true American citizens.

Works Consulted:

“Battle of Fort Wagner Facts & Summary”. American Battlefield Trust, 17 July 2020, www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/fort-wagner.

Robbins, Peggy. “The 54th Massachusetts’ War within a War”. Military History, 2003, p. 62-70. ProQuest, https://search.proquest.com/docview/212668658?accountid=13360.

Parent Map

Coordinates

Longitude: -79.876049700000