The Gold Coast

The triangle slave trade is the name given to the three-part water route taken by the slave transport ships while moving slaves from thier homes in Africa to the Americas and West Indies as slaves. For the ship and its sailors, this voyage started in Europe. Liverpool, England is one of the many ports Britannic ships would embark from. Other European ports include Nantes, Bristol, and Le Havre (4). These ships were outfitted with the goods necessary to, “exchange for captives in Africa” (2).

In spite of these influential ports and location cites, I choose to focus more on the sailor’s second leg of their journey: a voyage often referred to as “the middle passage”. It is here that the slaves solidify thier new roles as englaved people, and for them, it is the first oceanic leg of their journey (3). In Africa, at least 10% of slaves were bought and traded for in an area referred to as “The Gold Coast” (4).

Men, women, and children were brought from Central Africa (4) and as per the account given by Richard Miles, a fort officer who served on the Gold Coast, bought and traded slaves to ship captains, “subjected every AFtrican he considered purchasing to a humiliating bodily inspection, … to sift people according their health and age” (3). These inspections often included the inspection of one’s mouth to look for decaying teeth, dies in the hair to help gauge age, various tests to measure the captive’s sensory capacities, a close scrutiny of their genitals to look for venereal diseases. This can be summed up best in reiterating the enslaved people were, “thoroughly examined, even to the smallest Member, and that naked too both Men and Women, without the least distinction of Modesty” (3).

The treatment of the slaves did not improve as they were sold. In fact, “this process of unmaking, … produced a dramatic climate of terror in the world of slavery at sea that resulted in mental disorientation, familial and communal separation, malnourishment, lack of sanitation and cleanliness, severe isolation, debilitating diseases, sexual abuse, phychological instablilty, and bearing witness to physical violence commited against kin and shipmates” (1). This started as slaves were packed tightly together and, as was the case with the Zong, ship captains would attempt to transport dangerous numbers of slaves, allowing for the easy spread of disease amoungst the captives (3). They were packed below deck, the men having been shackled together in pairs by their ankles and wrists, for fear of an attempted uprising.

Due to the vast number of slaves “in crowded rooms below deck for long periods of time” they were “slowly poisoned by carbon dioxide, which steadily increased in concentration as hundreds of people exhaled in poorly ventilated spaces” (3). In addition to this, crew members did not allowing the slaves to frequently wash or shave themselves. Most slave ships consented to their washing once weekly/biweekly (3).

The women and children were often help in the back of the ship, separated from the men slaves. However, slave captains admitted that crews often abused them. Former slave Ottobah Cugoano later recalled, “It was common for the dirty filthy sailors to take the African women and lie upon their bodies” (2).

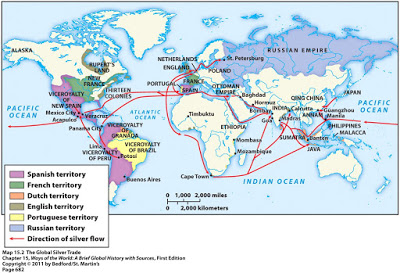

Scholars believe those who survived the voyage of the middle passage were scattered throughout 179 ports throughout the Americas. Some of these included those in Brazil, Jamaica, Haiti, the United States, etc (4). After selling the slaves, the ships would return back to Europe and resart the process once more, acting as en unstoppable engine powering the slave trade.

Works Cited

- Feelings, Tom. The Middle Passage. 375 Hudson St, New York, Penguin Random House, 2017.

- Mustakeem, Sowande. Slavery at Sea: Terror, Sex, and Sickness in the Middle Passage (New Black Studies Series). Illustrated, University of Illinois Press, 2016.

- Radburn, Nicholas. The Long Middle Passage: The Enslavement of Africans and the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, 1640-1808. 2016. Johns Hopkins University, PhD dissertation.

- “Slave Trade Routes.” Slavery and Remembrance, http://slaveryandremembrance.org/articles/article/?id=A0096.

Parent Map

Coordinates

Longitude: -2.090277800000