"The Picture of Dorian Gray" Context & Background

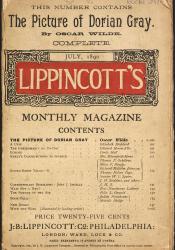

Oscar Wilde wrote his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, at the invitation of the American publisher, J. M. Stoddart, managing editor of the Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, who on 30 August 1889 gave a dinner in London at the Langham Hotel for Wilde and Arthur Conan Doyle. When Stoddart asked for a piece twice as long as Wilde’s fairy tale ‘The Fisherman and his Soul’, Wilde began working on The Picture of Dorian Gray. Stoddart's offer was attractive to a comparatively unknown author such as Wilde, whose literary career was not overwhelmingly successful at that time. J.B. Lippincott & Co. was one of the largest book publishing firms in Philadelphia and Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine a well-established American literary periodical that wished to increase its share of an expanding transatlantic market. Lippincott published their literary magazine from 1868 to 1915, and it included literary reviews, poetry, and short stories. In addition to Wilde, works by authors such as Rudyard Kipling, and Arthur Conan Doyle were published as well. In the summer of 1890, when the first edition of the novel was published in Lippincott's Monthly Magazine, the novel contained 13 chapters, and was criticized as scandalous and immoral (with detractors condemning its homosexual undertones and seeming embrace of hedonistic values.) Disappointed with its reception, Wilde revised the novel in 1891 and published it as a single volume, issued by Ward, Lock & Co (the London publisher which circulated the British edition of Lippincott's), adding a preface and six new chapters. This Preface was written as a response to those unkind critics of the first edition. It also succinctly sets forth the tenets of Wilde's philosophy of art. Devoted to a school of thought and mode of sensibility known as aestheticism, Wilde believed that art possesses an intrinsic value - that it is beautiful and therefore has worth, and thus needs serve no other purpose, be it moral or political. This attitude was revolutionary in Victorian England, where popular belief held that art was not only a function of morality but also a means of enforcing it.

Articles: