My Dearest Little Artist,

I hope this package finds you, unharmed from the grasping hands of your greedy younger brother--I do not mean to scorn him, but the manner in which your mother has decided to raise that child, that is to say completely devoid of correction and guidance, leaves me little faith in the future of the opposite sex. Alas, I digress.

I imagine you tucked away in your midwestern fields--green and humming with life sprung from dull roots out of the cruel april rain. I imagine this parcel finds you with pencil in hand, sketching wildflowers, or perhaps the neighbor's cat who would come into the yard, gracing me with the only company, save yours, worth having in that wilting little town--it always seemed to me she had the soul of a poet.

Enclosed you will find a care package of items for your birthday. Enclosed should be a fresh set of drafting pencils, a brand new sketch notebook, and, at the recommendation of a wonderful artist, Martin, 3 brushes and 3 different shades of red paint. Also enclosed, you will also find an edition of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam.

Allow me a moment to speak of each gift.

My companion, Zelda , and I found ourselves on Third Avenue--near 11th street--one evening, and wandered into an art supply store run by a wonderful Harold Steinberg. And while he was, indeed, most helpful, it was a fascinating young woman--Agnes Martin--an art student at Columbia, who enchanted me. We talked the night away, and she eventually invited Zelda and I to have dinner with her and her artist friends; it was quite the exciting night for us women in our 60s. We spoke of a great many things, including: the pros and cons of various paint brushes, the emotions evoked via various shades of violet, and the hue of red most representative of menstrual blood--A regrettable affliction God saw fit to bestow upon the female sex--as you you have begun to understand--to give the men a chance, I suppose. But I am veering off. It was a fine evening, and that is all to say--this paint is good.

As for this Edition of the Rubaiyat of Khayyam, it was printed two years ago and which I found at a book shop on Book Row. It is pocket sized, small enough to tuck into your satchel, and is covered in a glossy material that should protect it from those muddy rural roads. While it is to my great regret you haven’t grown quite the affection for literature as I have, this book may interest you. Perhaps if you find it enjoyable, you can write back to me with some of the books listed in the closing pages, and I will send them to you. But, I digress. This book was printed before we entered the war, and is one of the first editions of the Rubaiyat to be completely illustrated by Aiden Ross. 75 full illustrations to accompany this famous poem.

Indeed, the illustrations are necessary, little artist. I admit, I have never loved this book--and the front cover, with it’s --the art at least makes it tolerable. I remember this book well, my copy a bit more ornate--quite gauche, really--in the Barnard library; a worn embossed leather cover, the brassy scent of old paper mix the perfume of my peers as we sat reclined in a grove of each other's company. You must come out to me when it is time for you to go to college little artist--your talents cannot grow in the featureless fields of Ohio. I digress, again; you must forgive the ramblings of an old woman.

Turn to Quatrain XI, little artist, and you’ll see exactly whu I’ve never forgiven this book:

“A Book of Verses underneath the Bough,

A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Bread--and Thou

Beside me singing in the Wilderness--

Oh, Wilderness were Paradise enow!”

Do you see little artist? We are just objects in the paradise of men: swooning, singing, draping ourselves prettily for their pleasure. We do not read the book of verse, for we are singing. We do not eat the bread or drink the wine because we are singing. We are the wood nymphs of the wilderness, maintaining the places in which they leisure and giving them a song while we do it.

Perhaps by now you have found my secret--our secret-- tucked away in the leaves of this tome. Zelda brought back this cover to our apartment, “We can do it.” A calling to you--you are the future little artist, and you are needed. Look back at Quatrain XI, see the accompanying illustration? This is the paradise they envision for us, stick-thin, in a flowing dress draped and swooning over a lazy man who’s too oblivious to notice his book and wine are floating away down the stream.

We are objects for them to stare at, child, nothing more; should you ever forget, look at the woman on page 17.

Alas, even fools have merit once in awhile:

“The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

Moves on: nor all thy Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it.”

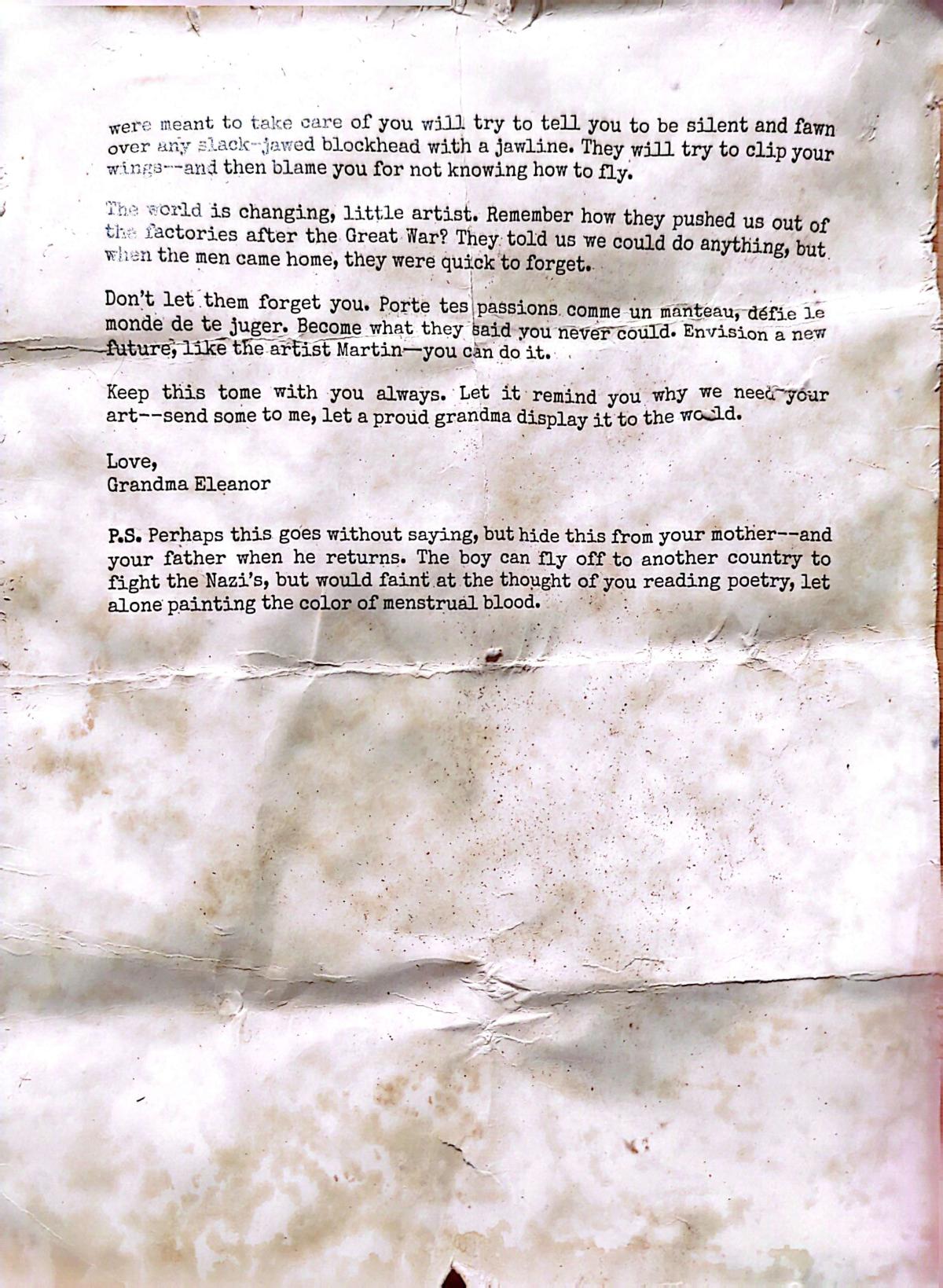

Let your own moving finger write, draw, paint, speak—do not let anyone tell you your place is only to be looked at, or sung to, or kept safe and silent. You have entered a dangerous time little artist, where those who were meant to take care of you will try to tell you to be silent and fawn over any slack-jawed blockhead with a jawline. They will try to clip your wings—and then blame you for not knowing how to fly.

The world is changing, little artist. Remember how they pushed us out of the factories after the Great War? They told us we could do anything, but when the men came home, they were quick to forget.

Don’t let them forget you. Porte tes passions comme un manteau, défie le monde de te juger. Become what they said you never could. Envision a new future, like the artist Martin—you can do it.

Keep this tome with you always. Let it remind you why we need your art--send some to me, let a proud grandma display it to the world.

Love,

Grandma Eleanor

P.S. Perhaps this goes without saying, but hide this from your mother--and your father when he returns. The boy can fly off to another country to fight the Nazi’s, but would faint at the thought of you reading poetry, let alone painting the color of menstrual blood.

Disclaimer for Posterity:

This letter is a work of fiction. While some historical figures (such as Agnes Martin) and cultural references appear within the text, all characters, correspondences, and events have been invented for the purposes of this speculative archival project. No real individuals were involved, and no actual edition of the Rubáiyát was gifted to a budding artist in Ohio by her radical grandmother in Manhattan—at least, not to my knowledge.

The document has produced and artificially aged for aesthetic purposes. Please do not mistake it for an actual historical artifact. (Though if you do, I’ll consider that a modest success.)