Introduction

“Want and sickness are too common in many stations of life to deserve more notice than is usually bestowed on the most ordinary vicissitudes of human nature.” -The Stroller’s Tale, Charles Dickens

In this gallery, you will bear witness to some of the horrors that went on behind the scenes for circus performers during the Victorian era. During this time, performers were treated as human commodities that came and went; If the show wasn’t fresh, or it wasn’t travelling somewhere new, then performers were usually left in the dirt, unpaid and forgotten. This lead to many performers forcing themselves to work more often, and on increasingly dangerous stunts. Some would risk their lives in order to be hired and able to perform to a crowd that wanted nothing more than to be awed and impressed. Some people, like Joseph Merrick, would flee to the circus in attempt to avoid the harsh environments of the workhouses, by showcasing his physical impairments under the stage name, “The Elephant Man”. Many people found success in their acts, such as Joseph Grimaldi, who redefined the persona of the clown in the late 18th century, even recruiting his son to follow in his footsteps. However, the seemingly inevitable end of both their careers would lead to separate but similar tragic stories of unworked nights and drowning sorrows. Henry Mayhew would go on to document some of the first-hand accounts of some of the performers in this gallery, including the Penny-Gaff Clown and The Strong Man. By the end of the 19th century, ‘Freak Shows’ as they were often called, would fall out of public endorsement, leaving many circuses closed down, leading to Joeseph Merrick losing any possibility of continuing his self-sustaining job as the Elephant Man; He would spend his final years in the care of Sir Fredrick Treves, who gained critical acclaim in the science field due to his study of Merrick.

Without further ado, continue if you wish, to see the unimaginable! The horrors of everyday life behind the showmanship of awesome delight! We truly stand on the shoulders of giants, and our entertainment is in part due to the hardships these preformers faced, as well as the carelessness that society has put upon them once they were left beaten and broken. I challenge you to compare and contrast the descriptions of these entertainers, and the images that bestowed their legacy; Dare to remember their plight, in newfound appreciation for the art of merrymaking in the Victorian Era.

Work Cited

Dickens, Charles. Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi. Richard Bentley, London. 1838. Project Gutenberg. 2014. Retrieved from: https://gutenberg.org/files/46709/46709-h/46709-h.htm

Dickens, Charles as “Boz”. The Pickwick Papers. Chapman & Hall. 1836-1837. Retrieved from: https://www.online-literature.com/dickens/pickwick/3/

Durbach, Nadja. “Skinless Wonders”: Body Worlds and the Victorian Freak Show. Project Muse. History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Vol 69. Jan 2014. Retrieved from: https://sites.middlebury.edu/freakishness/files/2014/07/BodyWorldsFreakShow.pdf

Mayhew, Henry. London Labour and the London Poor Vol III. Griffin, Bohn, and Company. 1861. Retrieved from: https://books.google.com/books?id=tVtHAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

Henry Mayhew & The Penny-Gaff Clown

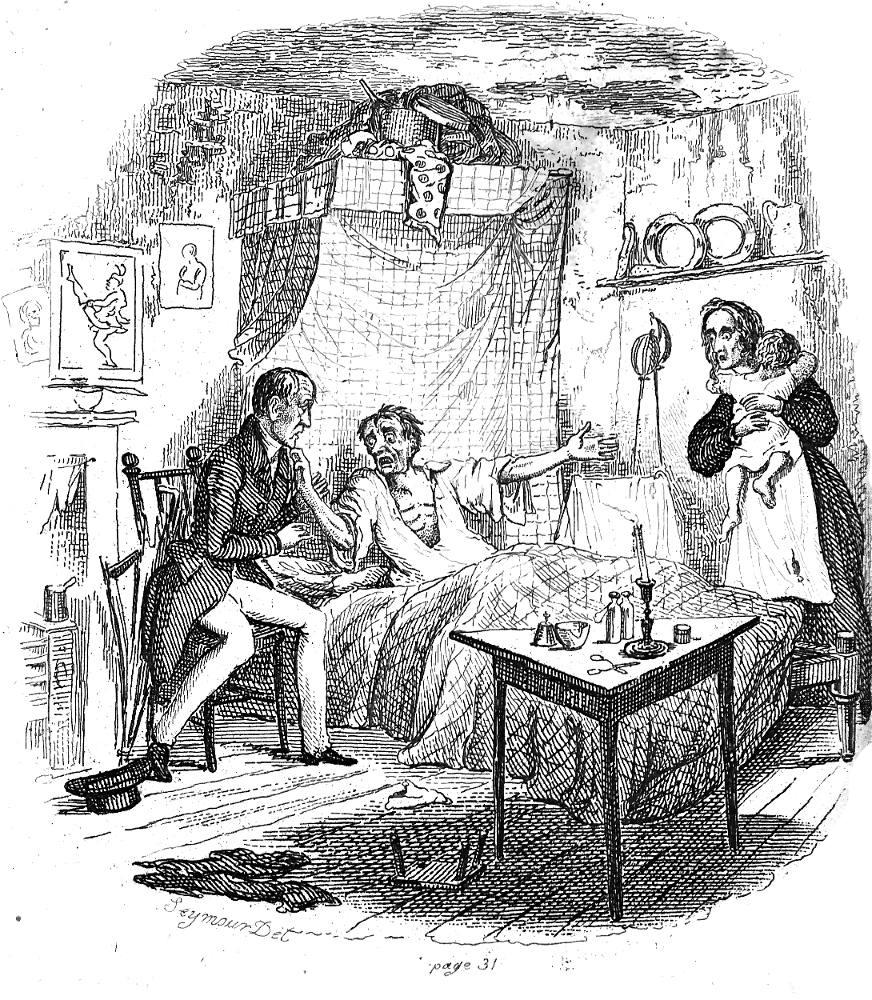

Fig. 1: Seymour, Robert. "The Dying Clown". Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens. April 1836. Retrieved from Victorian Web, https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/seymour/5.html

In an interview with “Funny Billy” (Mayhew, 121), as his companions called him, Mayhew reveals the depths at which clowning and pantomiming could (and often did) devolve into abstract poverty and indifferent treatment from their superiors. In one horrific tale, Billy was hit on-stage by an untrained stage-hand in an act, which caused his jaw to become dislocated. After committing to the Christmas-eve shows, which were put on multiple times a day to thousands of people, 12 hours later Billy found his jaw swollen so large it hung upon his shoulder. Instead of being taken to bed, Billy covered himself with face paint to hide the damage, “drowned my feelings in a little brandy, and so forth; and the next night I resumed my clowning.” Billy went on to write about his maddening illness that followed his dislocated jaw. He fell into a madness and trusted no one, including his wife, whom he said, “I’d seized her by the hair and fancied she was the man who had broken my jaw, and once I near strangled her.” (Mayhew, 122) Charles Dickens wrote of a shockingly similar story in his serialized publication The Pickwick Papers, under the pseudonym Boz. Chapter III, titled ‘The Stroller’s Tale’, a doctor hears of an old friend who asks for his assistance, upon meeting with the man, the doctor realizes his old friend (a former clown) has become disfigured:

His bloated body and shrunken legs--their deformity enhanced a hundredfold by the fantastic dress--the glassy eyes, contrasting fearfully with the thick white paint with which the face was besmeared; the grotesquely-ornamented head, trembling with paralysis, and the long skinny hands, rubbed with white chalk--all gave him a hideous and unnatural appearance, of which no description could convey an adequate idea, and which, to this day, I shudder to think of. (https://www.online-literature.com/dickens/pickwick/3/)

Funny Billy ended up losing his job and was forced to sell all of his furniture and children’s toys to avoid the workhouses. After seeing multiple dentists and doctors, he was told that an operation that would risk his life was needed to be done to remove an abscess and shattered teeth in his jaw. Upon refusal, Billy eventually fractured his own teeth and pulled them out piece by piece, cutting his gums with a pen-knife to remove fractured tooth parts. “If I hadn’t been a prudent, sober man, I should have died through it.” Billy said.

The Strong Man, Professor Sands & The Ceiling Act

Fig. 2: Unknown. Richard Sands performing at the Drury Lane Theatre, London. 1853. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Retrieved from: https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/the-story-of-circus#slideshow=58613815&s…

“I should a made a deal of money. There is a danger of course, but so there is if you’re twenty or thirty feet. They do it now fifty feet high, and that’s as bad as if you were two hundred or a mile in the air.” -The Strong Man

Richard Sands was an American performer who invented a death-defying trick in 1852 called the ceiling act. As early as 1853, Sands had reached London to perform the ceiling act to audiences at Surrey Theatre and Drury Lane. However, The Strong Man that Mayhew interviewed for London Labour and the London Poor Vol. III believes this was Sand’s assistant, as he had been informed that, “Sands killed himself on his benefit night in America. After walking on the marble slab in the Circus, somebody bet him he couldn’t do it on any ceiling, and he for a wager went to a Town-hall, and done it, and the ceiling gave way, and he fell and broke his neck.” (Mayhew, 103) After seeing another performer named Herman the Wizard do a ceiling act, The Strong Man began crafting his own ceiling act with rubber bottoms and hooks to walk on the cieling, upside down. Eventually The Strong Man sold his trick to another performer, who was not able to continue the act as he took a hundred weight along with him, “swung like a pendulum, and down he come.” After selling his trick, The Strong Man went back to being, well, a strongman. He stated that there were maybe 6 strongmen in London while he performed, often changing their names or titles as they pleased. However, like the Penny-Gaff Clown, The Strong Man stated that his earnings often went to wine, “The swells get hold of you. Perhaps a bottle of wine is called for, and then another; well, then a fellow must be no good if he doesn’t pay for the third when it comes, and the day’s money don’t run to it, and you’re in a hole.” (Mayhew, 104)

Joeseph Merrick aka “The Elephant Man”

“Tis true, my form is something odd

But blaming me, is blaming God,

Could I create myself anew

I would not fail in pleasing you.” -Joseph Merrick

Fig 3: Lynch, David. The Elephant Man. Brooksfilms. 1980. Retrieved from: https://www.framerated.co.uk/the-elephant-man-1980/

Joeseph Merrick was an extremely popular Victorian era ‘Freak Show’ preformer in the late 19th century. Merrick himself enjoyed his time as a performer, but he only persued such employment so as to avoid the work houses at the time. In fact, Merrick spent five years in the Leicester Union Workhouse before joining a circus and cooperating with the crew to make his own pamphlets and give himself a look more akin to an elephant than he actually was. Merrick and one of his managers manipulated the image to exaggerate Merrick’s “trunk,” a thick piece of skin that grew from his upper lip, and thus to enhance his persona as “the Elephant Man.” (Durbach, 55) Merrick has an interesting history in that much of the late 20th century exploration relied on the documents of Merrick’s examiner, Sir Frederick Treves. However, Treves calls Merrick by “John” in all his works, and has been noted as claiming falsities in the history of Joseph Merrick including locations of hospitals and certain dates of events. Merrick himself left the care of Treves stating he had been stripped naked and put on display as if an animal to doctors and curious scholars. Merrick joined a travelling circus in 1885, but by then ‘Freak Shows’ in England were being shut down as public opinion had shifted. Merrick was eventually cast astray, robbed, beaten, and stranded in Brussels by one of his new managers. Eventually Merrick took a train to Liverpool, where he was ridiculed and ogled by passersby, he was cornered in an alley where police found him hunched over, with only the business card of Frederick Treves to identify him. Merrick spent his final years in the care of Treves at the London Hospital, where he read, created miniature building models, and on one occasion visited the theatre during a Christmas showing. The Elephant Man directed by David Lynch and starring Anthony Hopkins and John Hurt was released in 1980. It portrayed Treves in mostly a positive light, and leaning into the idea that his circus manager, Tom Norman (Bytes, played by Freddie Jones in the film) was the crueler and more antagonistic authority in Merrick’s life. Norman, who’s freak shows had long been shut down after Merrick’s death said Treves was, “also a Showman, but on a rather higher social scale.” ... “[who] really exploited poor Joseph?” Pointing out that Treves was given public acclaim for his scientific research on Merrick, rewarding him with financial gain & becoming the surgeon to King Edward VII.

The Legendary Joseph Grimaldi

Fig. 4: Cruikshank, George. Joe's debut into the pit at Sadler's Wells. The Memoirs of Jeseph Grimaldi by Charles Dickens. 1838. Retrieved from: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8a/Joe%27s_debut_into_…

Joseph “Joey” Grimaldi was the most popular preforming clown to ever live during the era of the Victorian circus. Pictured here is his debut at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre in London. He was painted up as a monkey for the audience’s amusement, and strapped to a chain in which his father would sling him around with “utmost velocity.” Infamously, Joey was slung too fast by his father, and the chain snapped, causing him to be thrown into the audience. Luckily, an older gentleman was sitting down but giving all his attention to the performance, and was able to catch the boy without any harm. This is a stark contrast to the final image of Grimaldi’s acts, in which he sits in a chair because he has too many injuries to do any stunts in motion (https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f9/Joseph-Grimaldi-182…). Grimaldi popularized the modern clown, including white-faced paint and the contrasting colored pallet on the face and in the clothes. He was so popular that the term “Joey clown” would live on after Grimaldi had passed, with the same extreme caricatured happiness that we know and love today. His only son would follow in his footsteps, preforming as young as 18 months with his father. J.S. Grimaldi was unable to attain the massive success of his father, and would end up dying of unknown causes at the age of 30, depraved of fame, money, and living with his parents as a reclusive alcoholic. Grimaldi himself would live to be 58 years old, by then becoming an alcoholic, having very little money to his name, even fewer friends, and no remaining family members.