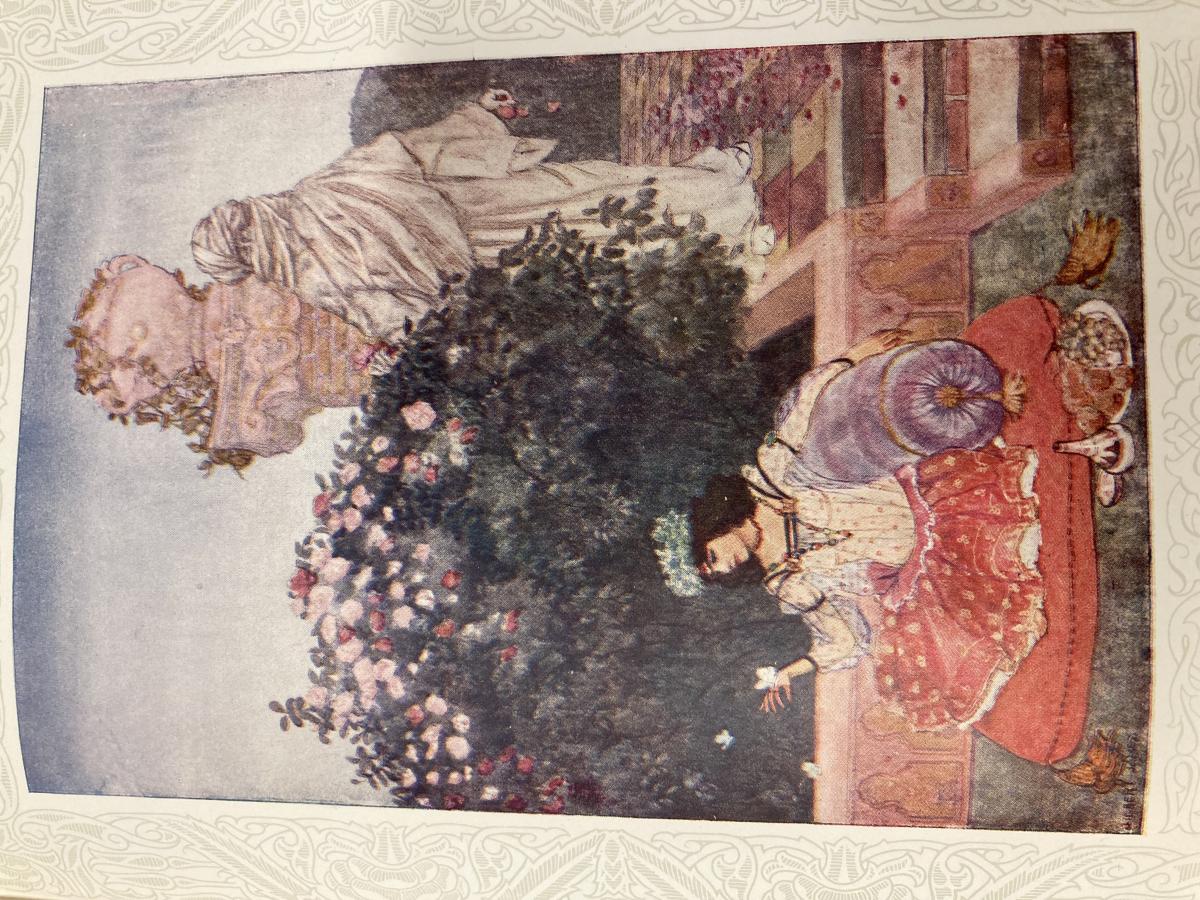

Central to the Oursler-Perkins edition of Rubáiyat of Omar Kháyyám are its colorful illustrative bookplates, courtesy of artist Gilbert James. Twelve of these inserts are scattered seemingly at random throughout the volume, their placement bearing relation neither to preceding nor subsequent quatrains. James’ work is rich in detail, focusing on a decidedly ‘exotic’ view of Kháyyám’s time and particularly concerned with displaying a pleasure-fueled lifestyle via copious amounts of food, wine, and nudity. The drawings rarely appear to attempt direct portrayal of their respective quatrain, rather configuring a key idea into a broader view of Eastern decadence and culture. For example, a drawing paired with quatrain XXIII [See Images 1 & 2] yet found between quatrains XLI and XLII portrays a woman atop a gold-lined cushion armed with wine and fruit, as a butterfly lands on her outstretched hand. Behind her, an unmentioned figure starkly resembling the angel of death as seen in quatrain XLIVIII [See Images 3 & 4] crumples the petals of the rosebush dividing them, expanding on the source material while perhaps hinting at a personal interpretation of the text. Similar to Nicholson’s introduction, James’ illustration reflects eager appreciation for the aesthetic beauty of both FitzGerald’s translation and the imagined, Orientalist-rendered Persia he intends to portray, appearing unconcerned with the intentions of Kháyyám or a good-faith rendering of his setting.

FitzGerald’s translation of quatrain XXIII completes a trilogy of quatrains reflecting on the impermanence of life and the urgency with which one must live it. His narrator warns of our fate, whence “into the Dust descend, Dust into Dust, and under Dust, to lie,” acknowledging that despite the seeming permanence of our being as recycled matter, the endless afterlife will be “Sans Wine, sans Song, sans Singer;” in other words, apart from the worldly pleasures that make life worth living (Kháyyám 83). The quatrain’s subject is ‘we,’ carrying over the pronoun used to indicate the narrator and his lover in the preceding verse. Despite this, the illustration accompanying quatrain XXIII lacks the male figure, replacing him with a foreboding robed individual less evidently entertained by the pleasures of wine and song partaken by the female figure. This mysterious humanoid hovers over a pile of tattered rose petals, of which several are clutched in his pale right hand, an image that perhaps suggests a resentment or longing held by the dead for the pleasures engaged in by the living. James’ image is doubtlessly engaged with the aesthetic and earthly delights regarded with such reverence in the verse, yet appears to posit a haunting, threatening personification of death clearly at odds with the melancholic tone of FitzGerald’s translation. Admittedly, James’ borrowing of details from a later stanza does recall the method of selective scissoring conducted by the translator, but his personal flourish here simply embellishes an already embellished source with a generic portrayal of an Eastern mystic.

Quatrain XXIII's female figure is observed taking advantage of her remaining time on Earth, in accordance with the narrator's code of beliefs. She is lounging in a relaxed, comfortable position, directly engaged with the natural world while good food and drink lie within arm's reach. Red dominates the picture's color scheme, with the woman's extremely detailed dress according with the hue of rose petals laid upon the bush behind her; curiously, there is little green applied to the bush in question, rather an increasing blackness as its base meets the upper half of the woman's body. This positioning of the bush as practically enveloping the woman along with the aforementioned mystic figure's pawing of it as if in command or anticipation further reflects James' fixation on mankind's inevitable descent into dust as being somewhat of a crushing experience in opposition to an indifferent inevitability, as it often comes across in FitzGerald's translated Kháyyám. James' Persia and the experiences to be had within it, as reflected in this image, thus becomes a temporary idyllic escape that must be treasuredand shared with others before it is too late to do so. In strikingly accenting the architecture and linens of his image, James assures the collector that this foreign land is as beautiful yet alien as they have imagined, yet in the displacement of his quatrain of interest within the larger organization of the edition the reader is reminded that, along with FitzGerald's translation and Nicholson's notes, the innards of any particular Rubáiyat of Omar Kháyyám are no more than the fantastical rendering of an unknowable time.

Kháyyám, Omar. Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. Trans. Edward FitzGerald, R & R Publishing,

date unknown