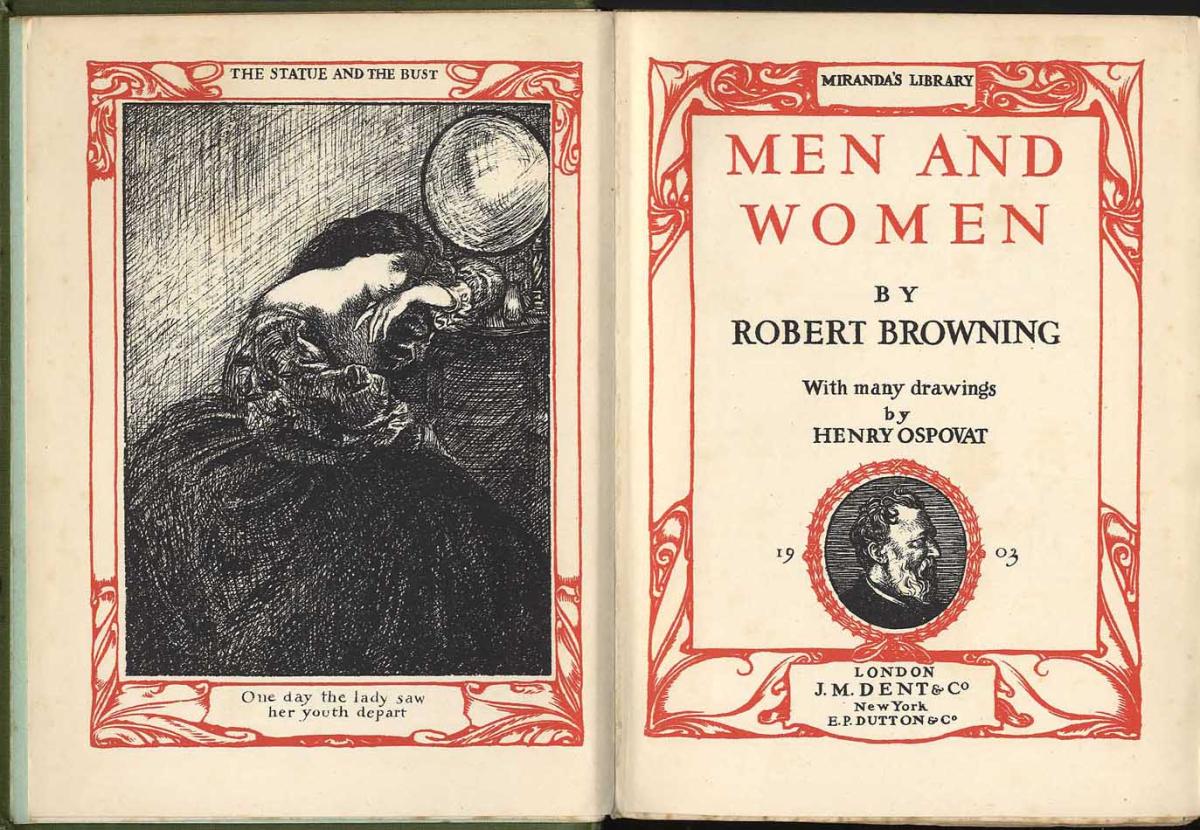

In “Concerning Geffray Teste Noire,” Morris engages with the dramatic monologue, the Victorians’ greatest poetic innovation. Morris experiments with the form throughout his first volume of poetry, The Defence of Guenevere (1858), in which “Teste Noire” first appeared. Critics generally cite Alfred, Lord Tennyson and Robert Browning as the two primary creators of the form, though recently some critics have argued that Felicia Hemans and Letitia Elizabeth Landon originated the form earlier in the century. While Tennyson and Browning composed monologues as early as the 1830s, the form found great popularity amongst other poets in the 1850s, just as Browning published his famous collection of monologues, Men and Women (1855), in the middle of the Crimean War. The dramatic monologue traditionally possesses certain conventions including a single speaker addressing a silent auditor.

Prior to the war, poets traditionally used the monologue to depict anti-social—sometimes homicidal—speakers disconnected from society, and this caused the form to become associated with madness. Browning’s canonical poems “Porphyria’s Lover” and “My Last Duchess,” for example, feature homicidal speakers. This association with madness can be seen in the 40s with Browning’s “Madhouse Cells” poems and in the 50s with Tennyson’s Maud, which concludes with the speaker joining the Crimean War. Dramatic monologues, thus allowed poets to explore society through individuals abjected from or at odds with it. Poets used the form to depict individuals breaking with or dismissed from communal life, often as a result of mental health.

We can see these concerns at play in “Teste Noire” within the speaker, John of Castel Neuf, who describes multiple war traumas, including witnessing the burning of many women seeking refuge in a church. Morris used the dramatic monologue in multiple poems in The Defence of Guenevere, including the eponymous poem.