The Custody of Infants Act of 1839 is often seen as the first feminist legislative victory in a long campaign to reform English marriage laws (Shanley 17, Chase and Levenson 40). While legal scholars have noted instances when a father’s total control over his legitimate children had been limited by judicial rulings prior to 1839 (Abramowicz 1345), the 1839 Act stands as the first major reform to recognize the rights of mothers. The important role played by Caroline Norton in the passage of the Act is also key to recognizing the law as a feminist triumph (Shanley 17).

Prior to the 1839 Custody of Infants Act, a father had a right to his legitimate children and was automatically granted custody if he and his wife separated for any reason (Bailey 393). Most fathers granted custody or access to the children’s mothers because it was considered ungentlemanly to deny mothers the opportunity to be with their children. Judges could also require a father to grant access or custody to the mother in circumstances in which the children’s welfare would be in jeopardy if they were left with their father. (Bailey 394) There were five major court cases in which judges ruled against mothers’ claims that set up the battle to legally recognize a mother’s right to see her children. In each case, the judge ruled against state intervention and in favor of paternal rights in an attempt to protect the stability of families (396).

The first case, De Manneville v. De Manneville (1804), involved a husband who blackmailed his wealthy wife by taking their baby away until she agreed to grant him greater financial support beyond what had been agreed upon in their marriage settlement. Despite Mr. de Manneville’s questionable character, Lord Chancellor Eldon granted him custody over his daughter; his reason was that awarding custody to the mother would have condoned her voluntary separation from her husband, which would have undermined the sanctity of marriage. (Bailey 396-98)

The second case, Ex parte Skinner (1824), involved a mother who sued for custody of her six-year old daughter after her husband was arrested and left their daughter in the care of his mistress. The judge ruled in favor of the father because he found no abuse in the case and, thus, had no reason to break with the father’s paternal right. (Bailey 399) Judges in the next three cases that awarded custody to fathers when the mothers would clearly have been more appropriate guardians based their judgments on the precedents set by De Manneville and Skinner (Bailey 400).

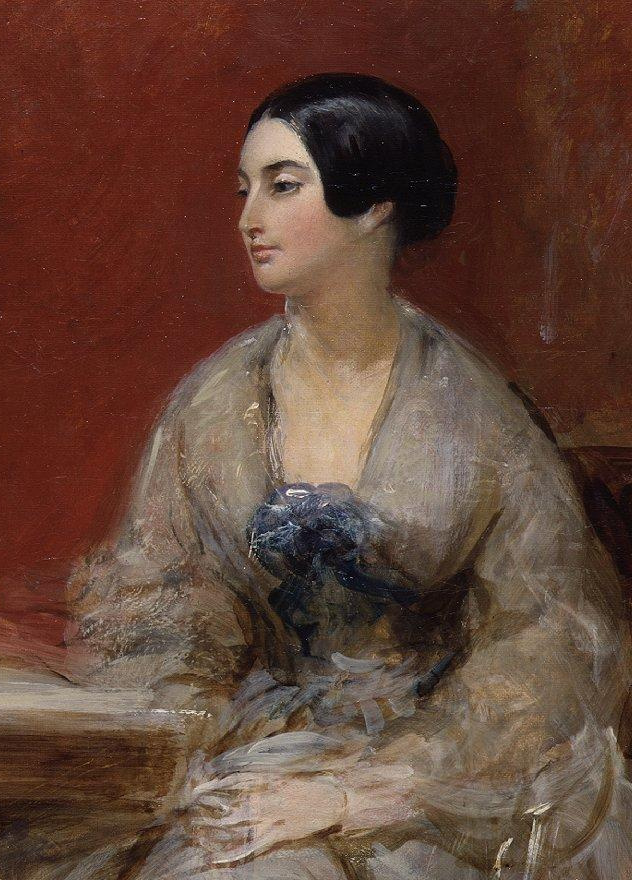

While the judges who ruled in the cases that followed De Manneville and Skinner were dissatisfied with needing to conform to the precedents that favored immoral fathers, there was little impetus to intervene with a legislative change until Caroline Norton took up the cause of establishing a mother’s right to her children. Mrs. Norton had been dragged into the public eye in 1836, when her spiteful husband accused her of having an affair with Lord Melbourne, who was prime minister of Britain at the time (Chase and Levenson 34). While Caroline and Lord Melbourne were found innocent, this could hardly be considered a victory for Mrs. Norton, since her reputation had been ruined and she had no means of seeking a divorce from the husband who loathed her. To make matters worse, George Norton decided to punish his wife by taking away their children and refusing to allow her to visit them. (Chase and Levenson 37-39)

In early 1837, Caroline Norton recruited Thomas Noon Talfourd, a young Member of Parliament and barrister, to bring a bill before the House of Commons that called for granting access to children under 12 years old to both parents (Bailey 410). While as a woman, Norton had no ability to argue on behalf of the bill before Parliament, she wrote a pamphlet outlining her argument and used her political connections to circulate it (Chase and Levenson 40). The bill that Talfourd presented met with vehement opposition from a few MP’s who objected on the grounds that guaranteeing mothers access to their children would encourage them to leave their husbands and serve as a disincentive to reconciliation between husbands and wives (Bailey 415).

The bill eventually passed the House of Commons with a large majority, but it was defeated in the House of Lords in July 1838 primarily due to a fear that it would promote the dissolution of families. (Bailey 425) Norton responded with a new pamphlet in which she refuted every argument against the bill that had arisen in Parliament. Here, as in all of her other writing on behalf of the rights of women, Norton took the position that women were indeed inferior to men, but that such inferiority did not mean they should not be protected by the law. She wrote, “An inferior position, that is, a position subject to individual authority, does not imply the absence of claim to general protection. To say that a wife should be otherwise than dutiful and obedient to her husband, or that she should in any way be independent of him, would be absurd …. But there is a very wide difference between being subject to authority and subject to oppression” (Norton 6). While some historians view this as Norton’s genuine belief in women’s inferiority (Shanley 18), others interpret her position as a shrewd political move calculated to prevent her male audience from dismissing her arguments outright (Bailey 406).

In April 1839, Talfourd brought to the House of Commons a new version of the bill, which allowed mothers to claim custody of children under age seven and to have access to older children (Bailey 433). It passed the House of Commons in June 1839 (Bailey 434) and the House of Lords in August 1839 (Bailey 436). While the law didn’t significantly change the way custody was awarded by the courts, since in most cases mothers had already been allowed either custody or equal access to their children (Bailey 393), it did provide legal recognition of a mother’s right to see her children and served as a first step toward acknowledging the need for legal protections for married women.

Works Cited:

Abramowicz, Sarah. “English Child Custody Law, 1660-1839: The Origins of Judicial Intervention in Paternal Custody.” Columbia Law Review, vol. 99, no. 5, June 1999, p. 1344-1392.

Bailey, Martha J. “England's First Custody of Infants Act.” Queen's Law Journal, vol. 20, no. 2, Spring 1995, p. 391-438. HeinOnline.

Chase, Karen and Michael Levenson. The Spectacle of Intimacy: A Public Life for the Victorian Family. Princeton UP, 2000.

Norton, Caroline. A Plain Letter to the Lord Chancellor on the Infant Custody Bill. James Ridgway, 1839. Google Books.

Shanley, Mary Lyndon. Feminism, Marriage, and the Law in Victorian England, 1850-1895. Princeton UP, 1989.