A variation of this description was originally published at The Rossetti Archive.

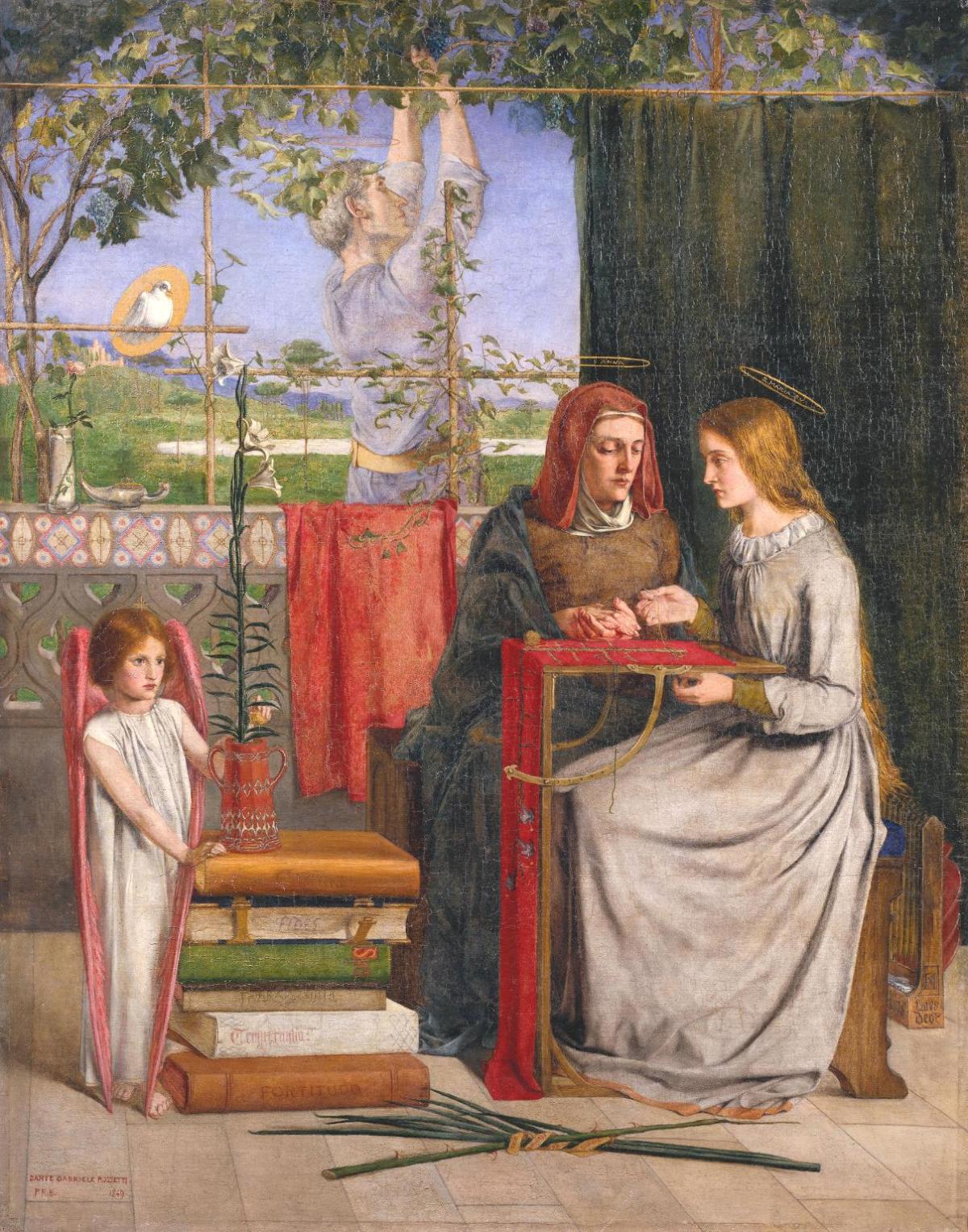

Dante Gabriel Rossetti's own description of the work, given in a 14 November 1848 letter to Charles Lyell, is primary: “It belongs to the religious class which has always appeared to me the most adapted and the most worthy to interest the members of a Christian community. The subject is the education of the Blessed Virgin, one which has been treated at various times by Murillo and other painters,—but, as I cannot but think, in a very inadequate manner, since they have invariably represented her as reading from a book under the superintendence of her Mother, St. Anne, an occupation obviously incompatible with these times, and which could only pass muster if treated in a purely symbolical manner. In order, therefore, to attempt something more probable and at the same time less commonplace, I have represented the future Mother of Our Lord as occupied in embroidering a lily,—always under the direction of St. Anne; the flower she is copying being held by two little angels. At a large window (or rather aperture) in the background, her father, St. Joachim, is seen pruning a vine. There are various symbolic accessories which it is needless to describe” (Fredeman 1848.12).

Scholarly Commentary

Introduction

The Girlhood of Mary Virgin was Dante Gabriel Rossetti's first major oil painting. Exhibited in 1849 at the Free Exhibition in London, it carried the initials “PRB” (for “Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood”). The initials announced (in coded form) the arrival of a new movement in British art.

Like his Pre-Raphaelite brothers William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, Rossetti had intended to submit the picture to the Royal Academy's spring Exhibition in early April, but at the last minute he changed his mind and showed it at the (juryless) Free Exhibition, which opened in March before the Royal Academy show. Hunt was put out by the event and suspected Rossetti of wanting to steal a march on their work, but the truth is probably otherwise. Rossetti was quite nervous about the reception of his picture and may well have feared that the Academy wouldn't have accepted his painting. Besides, Ford Madox Brown was showing his new work (King Lear) at the Free Exhibition and may have influenced Rossetti's decision.

Attached to the picture was a gold-faced sheet of paper containing two sonnets on the painting. (This gold sheet is no longer with the painting.) The first sonnet is a verbal translation of the iconographical details; the second is a literalization of its Catholic symbology. Painting and sonnets together define the special kind of composite art that Rossetti practiced—an art epitomized in those works that comprise a “double work of art,” a work with both poetical and pictorial components. Typically with such works, Rossetti would execute a painting and then write one or more poems to comment on the painting or interpret it. The Girlhood of Mary Virgin is just this kind of work. The Blessed Damozel, on the other hand, first appeared as a poetical work.

Although it shares many characteristics of the highly detailed, even naturalistic style of Hunt and Millais, the picture is anything but an exercise in Pre-Raphaelite “realism.” It is far too literal in its handling of its subject and its accessories, as the constellation of the young angel, the watered lily, and the books most dramatically show. It is also far less meticulous in its rendering of small details than either Hunt or Millais were in their work. The spirit driving this picture is the spirit of pastiche, which here becomes a vehicle for the presence of what Rossetti liked to call “Mystery.” As Brown saw, the painting is a kind of magical exercise designed to call back the spirit that informed the pictorial work of primitive Christian art: as if a devoted act of careful imitation might be able to recover the spirit of a lost world. The presence of the books is especially revealing, for while they might be thought anachronistic in relation to the legendary subject, they are precisely historical as figural forms drawn out of a medieval stylistic imagination. This is a romantic and even a Faustian painting; its desire is directed toward the realization of an ecstatic ethos, an impersonal absorption in the spiritual forces that stand within the subject of the painting. The painting is the work of an artist who wants to be caught up, in exactly the way that the young Mary is being caught up, by mysterious and impersonal divine agencies. To Rossetti however, if such agencies operate in the world, they are most fully realized in an artistic expression devoted to their revelation.

Production History

Begun in the summer of 1848, Dante Gabriel Rossetti worked hard at the picture right up to its exhibition the following March. He began it while living with Holman Hunt at their Cleveland Street lodgings, and both Hunt and Brown supervised much of the work. Rossetti “made several studies in chalk for the picture, besides the design for the composition” (Fredeman 1848.12). He had finished the background by late August 1848.

Virginia Surtees says that Rossetti planned to make the picture the central panel of a triptych, with the side panels “depicting the Virgin planting a lily and a rose, and the Virgin in the House of St. John” (Surtees 11). (See his early pictures Mary Nazarene and Mary in the House of St. John.) But this planned triptych was to have had a new and altogether different central panel—one depicting Zachariah and Elizabeth joining the Passover of the Holy Family (see The Passover in the Holy Family: Gathering Bitter Herbs and Rossetti 13).

Reception

The painting was well received, for the most part, as were the other new Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood paintings exhibited by William Holman Hunt (Rienzi) and John Everett Millais (Isabella) at the Royal Academy Exhibition. Dante Gabriel Rossetti's painting was bought for 80 guineas by the Dowager Marchioness of Bath, who was a family acquaintance. Thus, the Pre-Raphaelite movement's initial appearance in the art world was by no means unsuccessful (Ghose 21-24). However, a year later when their work was exhibited at the 1850 Royal Academy and Portland Gallery Exhibitions, the reception would be very different.

John Orchard wrote a pair of bad sonnets on Dante Gabriel Rossetti's picture that both CR and William Michael Rossetti comment upon (see Family Letters of Christina Rossetti 4-5); one began “Musing, not seldom to my eye of mind”,” the other “The guileless modesty of soul full sure.”

Iconographic

The picture treats a subject drawn from the legendary history of the life of the Madonna. In good (early) Pre-Raphaelite style, Dante Gabriel Rossetti handles the work by treating the entire apparatus in a realistic, or historicist, manner. That is to say, the painting attempts to give a faithful (historical) representation at two levels simultaneously: at the level of the original narrative materials, from the primitive history of Christianity, and at the level of the symbology, which Rossetti defines in medieval terms. For all its elaborate set of symbolic details, therefore, the picture is anything but symbolical. Indeed, its entire approach is literalist—a fact emphasized by the original frame of the picture, which was designed to give it an antique, “medieval” appearance.

Rossetti’s two sonnets for the painting explain most of the work's Christian symbology. However, the sonnets do not point out that the trellis on which St. Joachim is working puts a cross at a central position in the picture, or that the vine alludes to the True Vine (i.e., Jesus), or that the red cloth draped at the center signals the robe of Christ's Passion. Indeed, Mary is represented as embroidering a garment that alludes to the same robe. The rose and the lily are both the Madonna's flowers, and the lamp signifies piety. The painting's colors are carefully chosen, as one sees most particularly in the case of the stack of books, which are color-coded to the virtues they represent. Virginia Surtees points out that the trellis-cross is twined with ivy “which the artist here uses for the first time as a symbol of ‘clinging memory’” (Surtees 10). Waugh notes that the seven cypresses represent “the seven sorrowful mysteries” (Waugh 25).

Linguistic forms populate the canvas (and the integral frame). Rossetti often incorporated such verbal elements in his pictures—a device he borrowed from medieval styles—in order to increase the conceptual and abstract character of his work. Here the names of the virtues appear on the book spines (Fortitudo, Temperentia, Prudentia, Spes, Fides, and Caritas); "the gilt haloes are inscribed S. Ioachimus, S. Anna, S. Maria S.V.;" a scroll binding the palms and briars bears the legend “Tot dolores tot gaudia;” and the portable organ near the hassock is carved with the initial M and has the inscription “O sis, Laus Deo.”

The painting inaugurated a whole series of related pictorial treatments of the Madonna over the next few years, in various media. Ecce Ancilla Domini! is the most closely related and was the next to be begun.

Pictorial

Treatments of the Madonna, whether in a legendary or a symbolical mode, are of course numerous, but Dante Gabriel Rossetti was particularly interested in medieval representations. He mentions Murillo but he might as well have cited any number of others. Alicia Craig Faxon notes the possible influence of a woodcut Christ and Mary Before a Grape Arbor, plate 35 in the 1465 Canticum Canticorum which Rossetti could have seen at the British Museum (Faxon 53).

But the most important influences on this work, and related earlier pieces, were Ford Madox Brown and William Holman Hunt, both of whom tutored Rossetti in painting technique. The influence of the Nazarenes, in particular of Overbeck, is secondary, via Brown's interest in their work. Hunt's insistence on the need to paint from “Nature,” which became a key point of the Pre-Raphaelite program, has clearly affected Rossetti's work here. Hunt's point embraced not only using “real” persons and objects as models for pictorial images, but also working with materials and techniques that would be “truthful” to the ideal of Nature. This meant using pure colors and being careful of technical accuracy, particularly in the treatment of details and in the drawing.

But even here Dante Gabriel Rossetti's distinctive way of proceeding with a picture is apparent, and very different from Millais or Hunt. Brown was right when he compared this work to early Christian art, for the simplicity of the picture is not at all naturalistic, as is the work of Millais and especially Hunt; it is decidedly hieratic and abstract.

The contemporary work that the picture most recalls is Brown's Wycliffe Reading his Translation of the Bible to John of Gaunt. One notices the similarity in painting technique, especially the pale coloring. The child-angel with the books is an echo of Brown's Our Ladye of Saturday Night.

Literary

Besides the two sonnets directly connected to the painting, the picture forms part of a whole series of related pictorial and poetical works that Dante Gabriel Rossetti had been making since 1847, and that he continued to be preoccupied with through the 1850s. These include his projected series of Songs of the Art Catholic as well as his Dantescan works (like The Blessed Damozel) that are concerned with Beatricean figures.

Rossetti may well have used Mrs. Anna Jameson's popular Legends of the Madonna (1848) as a reference work for the details in his painting.

Physical Description

Medium: Oil on canvas.

Technique: William Bell Scott described Dante Gabriel Rossetti's work on the painting in the following terms: “He was painting in oils with water-colour brushes, as thinly as in water-colour, on canvas which he had primed with white till the surface was as smooth as cardboard, and every tint remained transparent” ( Scott 250).

Dimensions: 83.2 x 63.5 cm.

Frame: According to Alastair Grieve, “On the original frame Rossetti had inscribed his sonnet explaining the symbolism [Sonnet I], while a second sonnet [i.e., Sonnet II] . . . was printed in the catalogue of the Free Exhibition. Both sonnets are inscribed at the bottom of the present frame” (Grieve 65). Surtees, however, says that “The two sonnets were printed on a slip of gold-covered paper and fixed to the frame of the picture. (They are now on the back.)” (Surtees 11). That slip of paper, however, does not seem to be preserved anywhere in the Tate Gallery. The picture was reframed in 1864 when Dante Gabriel Rossetti was repainting parts of it. He changed “what had been a frame with curved top corners to a rectangular design of the type he had evolved with Brown earlier that decade. The picture was therefore originally more archaic in appearance” (Rossetti 64). Rossetti then had the two sonnets inscribed next to each other on the frame below the painting.

Signature: Dante Gabriel Rossetti P. R. B. 1849.

Note: This is the first picture to declare itself a “Pre-Raphaelite” work by carrying the initials of the movement as part of its signature.

Production Description

Production Date: 1849.

Exhibition History: Free Exhibition, Hyde Park Corner, 1849; RA, 1883; Nottingham Art Gallery, 1892; New Gallery, 1897; Bradford Exhibition of the Fine Arts, 1904; Manchester, 1911; Tate, 1923; Tate, 1948; Royal Academy, 1934; Birmingham, 1947; Tate, 1984.

Copy: Daguerreotype (photographer unknown) reproduced in W. Holman Hunt's Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood vol. 1, 365 (facing page).

Patron: Dowager Marchioness of Bath.

Date Commissioned: July 1849.

Original Cost: £80.

Model: Frances Polidori Rossetti.

Note: Mrs. Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti's mother, sat for St. Anne.

Model: Christina Rossetti.

Note: Christina Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti's sister, sat for the Virgin.

Model: “Old Williams.”

Note: “Old Williams, employed by the Rossetti family, sat for St. Joachim” (Surtees, Pictures and Drawings 10).

Model: “Gabriel made a study, from a girl whom Collinson recommended to him, for the head of the angel” (Rossetti 1). This was done in August 1849, when Dante Gabriel Rossetti was repainting parts of the picture. The original angel's face is said to have been modelled on Thomas Woolner's half-sister (Surtees, Pictures and Drawings 10).

Repainting: August 1849.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti repainted “the dress of the Virgin and the angel's face” before sending the picture to the Dowager Marchioness of Bath, who had purchased it (Rossetti 64).

Repainting: 1864.

The painting was sent to Dante Gabriel Rossetti in late 1864 for repainting by its owner at that time, Lady Louisa Fielding. According to Grieve, the picture was reframed at this time, and Rossetti “altered the angel's wings from white to deep pink and the Virgin's sleeves from yellow to brown” (Rossetti 64).

Provenance

Current Location: Tate Gallery.

Catalog Number: 4872.

Purchase Price: Bequest.

Note: Bequest of Lady Jekyll (1937).

Archival History: The painting was given by the Marchioness of Bath to her daughter Lady Louisa Fielding, and William Graham purchased it in 1885, from whom it passed to his daughter Lady Jekyll.

Works Cited

Faxon, Alicia Craig. Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Abbeville Press, 1989.

Fredeman, William E. The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. D. S. Brewer, 2002.

Ghose, S. N. Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Contemporary Criticism (1849–1882). Dijon: Darantiere, 1929.

Grieve, Alastair I. The Art of Dante Gabriel Rossetti: The Pre–Raphaelite Period 1848–1850. Real World Publications, 1973.

Harrison Anthony. The Letters of Christina Rossetti. vol 4. University of Virginia Press, 1997-2000.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. The Pre–Raphaelites. Tate Gallery, 1984.

Scott, William Bell. Autobiographical Notes. Ed. W. Minot. Vol 2. Harper Publishing, 1892.

Surtees, Virginia. The Paintings and Drawings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882): A Catalogue Raisonne. vol 1. Clarendon, 1971.

Waugh, Evelyn. Rossetti: His Life and Works. Duckworth, 1928.

How to Cite this Web Page (MLA format)

McGann, Jerome. “Dante Gabriel Rossetti, The Girlhood of Mary Virgin (1849).” Rossetti Archive Galleries. The COVE: The Central Online Victorian Educator, covecollective.org. [Here, add your last date of access to The COVE].