In part two of On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums, Barbara Black argues that the nature of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám’s popularity as a gift book is directly related to Orientalism. The way the Western public consumed the Rubáiyát was as an exotic piece of art. By approaching something as exotic, it is inherently othered and simultaneously conquered (Black 63). On pages 60-61, she states: “Susceptible to a minimizing that is consistent with the popular miniature packaging of the Rubáiyát, this poem’s value becomes inseparable from its pretty, crafted, possessable diminutiveness.”

This diminutiveness is the symptom of Orientalism, and is exaggerated by decorations like locks, jewels, gilding and illustrations depicting stereotypical Persian people. The very appearance that makes a book a gift book—the very qualities that make it treasure—make it something to be possessed. In British history, possession and museums played an important role in establishing colonial power. Thus, to collect a piece of literary culture, Black argues, one establishes dominance over that culture. It is doubly complicated by FitzGerald’s role in the Rubáiyát’s explosion in popularity.

When approaching this discussion, however, complicating factors quickly appear: is owning a plain copy of the Rubáiyát different than owning a very decorative edition when it comes to “possession” of a culture? Do the intentions of the owner affect the dynamic of ownership? With the Little Luxart Library edition, there’s the additional question of whether or not the works the Rubáiyát is compiled with makes a difference in this discussion.

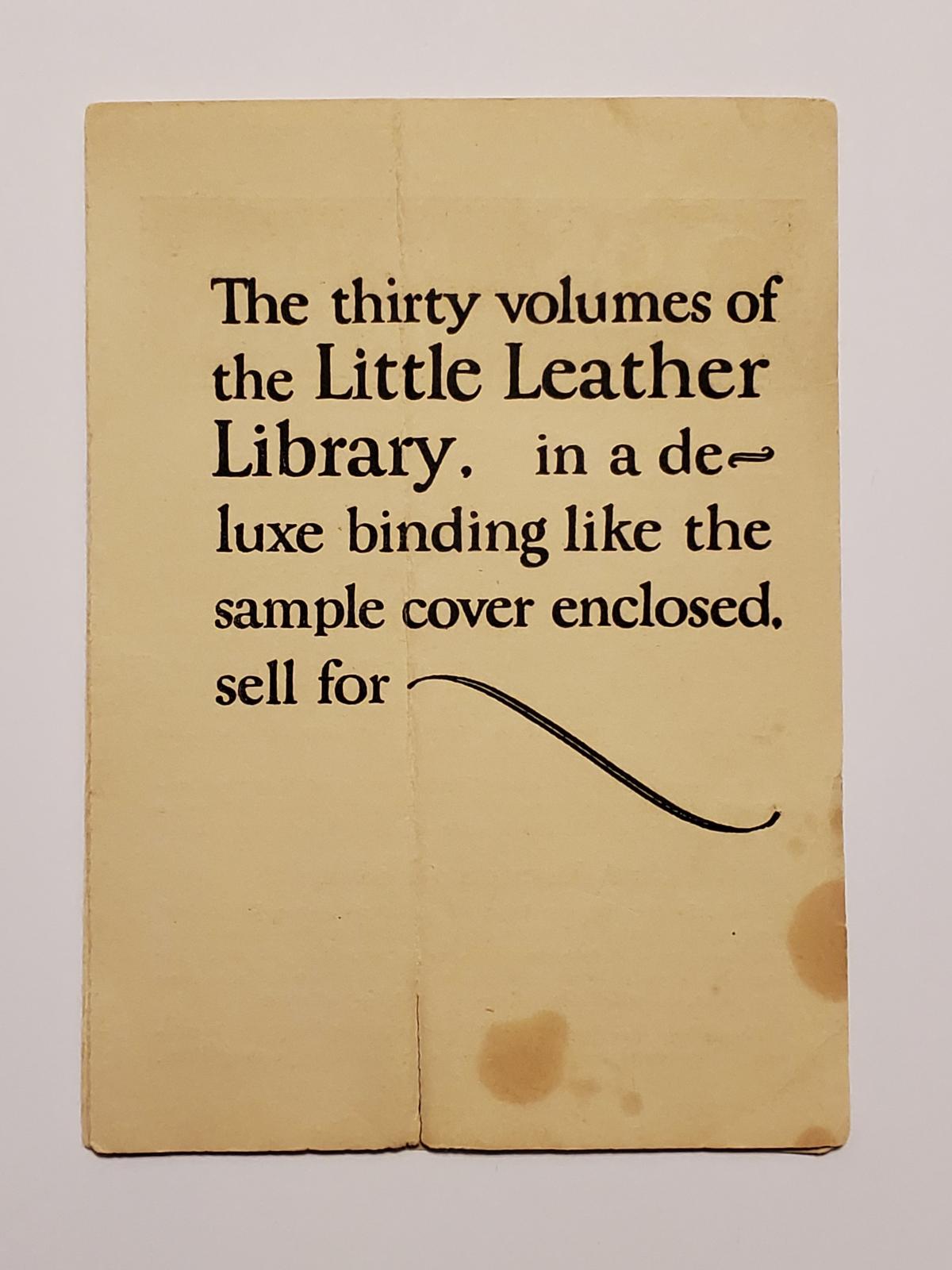

In the advertisements published for the Little Luxart Library, “masterpiece,” and “best of the world’s literature” (see second image) are used to describe the collection—and, by extension, the Rubáiyát. Published and sold alongside Kipling, Wilde, Shakespeare and Tennyson, the Rubáiyát is listed first (see fifth image). This is a place of honor; the list isn’t in alphabetical order, it’s likely by popularity.

Yet these thirty books are meant to be possessed; they would look lovely as a set sitting on a bookshelf. They are meant to be possessed, meant to be looked at. But they’re also meant to be read! Unlike some of the larger, more obviously decorative books described in the ENG 470 Group, the Little Luxart Library edition of the Rubáiyát is small enough to be easily carried. Any of these thirty little books, then, would be ideal for travel. Their lack of exterior decoration and the heavier paper also lend themselves well to real use. The highest praise a book can be given is to be read repeatedly.

Despite the qualities that make this Rubáiyát so good for traveling, despite its seat of honor amongst literary masterpieces (see images), this function of the Rubáiyát as a piece of a collection instead of a whole serves Orientalist purposes. “To envision the Rubáiyát in the home, as a drawing-room collectible, shows it at its most powerful (Black 63).” In what Black calls a “museum culture” on page 60, to be small, to be possessed like treasure is to be diminished and to be colonized.

Additionally, the author credit for the Rubáiyát is given to FitzGerald in the Little Luxart Library set. While this isn’t unusual, the continued emphasis placed on FitzGerald removes the elements of Islamic culture and makes it impossible to dicuss the Rubáiyát in terms of cultural appreciation; in addition to “prettifying” many lines of the poem, FitzGerald “Orientalized” the poem with the intention of appealing to British readers (Black 62-63).

By making the original authorship of the poem part of the title, too, we see the author diminished. The inclusion of Khayyám’s name in the title suggests a sense of fictionality; it makes him a narrator of FitzGerald’s words instead of a poet in his own right.

While a small red book by itself isn’t responsible for the spread of Orientalism, it very much can be a vessel for Orientalism. So our little red book must be understood for the role it plays in both complicating the relationship between translator and poet, and for the role it plays in objectifying a culture.

Works Cited

Black, Barbara J. On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums. University Press of Virginia, 2000. Accessed 22 April 2023.

“Little Leather Library Collectors.” Little Leather Library Collectors, https://littleleatherlibrary.com/brochures.html. Accessed 23 April 2023.