Barbara Black, in her book On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums, argues that the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám has been objectified through its popularity as a gift book. The poem's value has become inseparable from its physical presence as a small, pretty, and crafted object. Black suggests that this objectification has resulted in the Rubáiyát being entrenched in the categorically Oriental, and has been appropriated by FitzGerald himself, audiences, and publishers in the decades following the initial translation. She writes, “This poem’s value becomes inseparable from its pretty, crafted, possessable diminutiveness. Khayyám’s verse remains entrenched in the categorically Oriental, in the land of seers and Eastern serenity” (61). In other words, the poem has been reduced to a decorative object, divorced from its original cultural context.

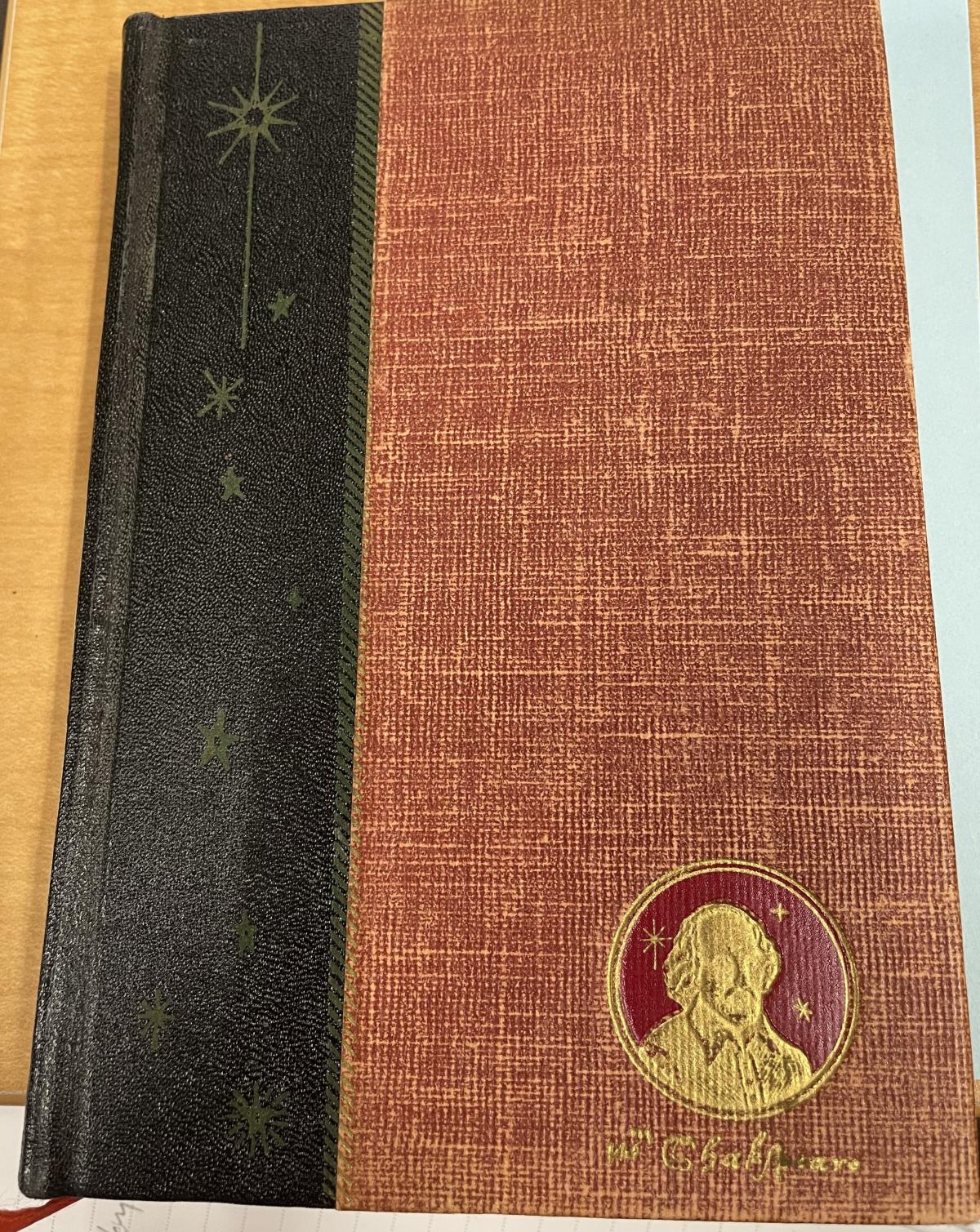

The 1951 Shakespeare House Sullivan Edition of The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, illustrated by Edmund J. Sullivan, exemplifies Black's argument in some ways, but it also displays evidence of other ways of thinking about cultural translation. The book's cover, with its elaborate flyleaf texture, ornate gold letterings on the spine, and the gold edging of the pages, presents the poem as a precious and beautiful object, which could be seen as a reflection of the objectification Black describes. Having Shakespeare House as the publisher of this edition can evoke quality, targeting a Western audience. (See Figure 1) However, the book's preface, written by the translator, Edward FitzGerald, suggests a more respectful approach to the cultural translation of the Rubáiyát. FitzGerald notes that his translation is "more than anything else Oriental in character," and he acknowledges the limitations of his translation, stating that he has "made no attempt to be faithful to the original."

Evidence from the edition supports both Black's argument and the idea of respectful cultural translation. The illustrations by Sullivan, while beautiful, could be seen as objectifying the poem, perhaps even considered to be an exaggeration of the East. Sullivan's style is highly ornate, and his depiction of Eastern culture is stylized and exoticized. The illustrations depict, what readers can assume to be, Khayyám in various states of contemplation, surrounded by images of nature and the cosmos. Some of the illustrations depict Western biblical allusions which juxtaposed with the remaining illustrations create a dissonance that brings out the Oriental or Eastern characteristics of the other images. (See Figure 2) While the illustrations could be seen as contributing to the objectification of the poetry, especially since most of the illustrations show oversexualized/naked women and drunk-bearded men (See Figures 3 & 4), they also serve to enhance readers’ appreciation for the beauty of Khayyám’s verses, as the style is meant to capture the eyes of the collectors. Most of Sullivan’s illustrations invite the reader to consider the philosophical themes of the text, rather than simply admiring the artwork. The illustrations are intricate and detailed, providing readers with a visual representation of the themes and ideas expressed in the poetry, as well as showing a level of nuance and detail that suggests a respectful curiosity toward Eastern aesthetics. Sullivan’s illustrations are not merely decorative but serve to enrich readers’ understanding of the text.

However, the book's typography is simple and unassuming, with a clean, modern font that is easy to read. There is nothing in the typography that further exemplifies the Oriental, as it is not written in a font that can be viewed as “Eastern”. The combination of Eastern and Western elements highlights the intersection between two different cultures and creates a unique visual appeal. The juxtaposition between the Western-style font and Eastern illustrations raises questions about cultural translation and appropriation. On one hand, the use of a Western-style font for the English translation of Khayyam's poetry can be seen as an attempt to make the text accessible to Western readers. However, the use of Eastern-style illustrations highlights the fact that the book's content and themes are inherently Eastern in nature. While the use of a Western-style font could be seen as an attempt to make the text accessible to Western readers, the Eastern-style illustrations raise questions about cultural translation and appropriation. (See Figure 5)

As a whole, the 1951 Shakespeare House Sullivan Edition of The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám exemplifies some aspects of Black's argument about the objectification of the poem. However, the book's preface, typography, and endpapers suggest a more respectful approach to cultural translation. These elements suggest that the Sullivan edition of the Rubáiyát is an exception to Black’s thesis of objectification. Rather than reducing the work to a decorative object, the publishers of this edition valued education, respectful curiosity, and beauty. The cultural differences between East and West are acknowledged and celebrated, rather than papered over or ignored. The illustrations reinforce the themes of the text, inviting the reader to engage with the philosophical and mystical themes of the work. Finally, the high quality of the materials and production suggest that the publishers valued the beauty and craftsmanship of the book, while still valuing the content of the text. Ultimately, the edition offers a nuanced perspective on the relationship between translation, beauty, and cultural appropriation.

Works Cited:

Black, Barbara. On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums. University of Virginia Press, 2000.

FitzGerald, Edward. The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: Translated from the Persian. Illustrated by Edmund J. Sullivan, Shakespeare House, 1951.