In her chapter, Fugitive Articulation, Barbara Black argues that Edward Fitzgerald’s translation of Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám and the gift book culture that it spawned is an example of Orientalism. The text’s initial allure, a translation of a Persian poem about lavishing in the pleasures of life and indulging in excess, is in Black’s argument, heightened not only by Fitzgerald's translation choices but also by how the book was packaged and published. The gift book culture that the Rubáiyát spawned, Black argues, shows how what makes the text value is the idea of owning something that is alluring, like a jewel. This is reflected in lavish illustrations and fonts used to create gift book editions of the Rubáiyát.

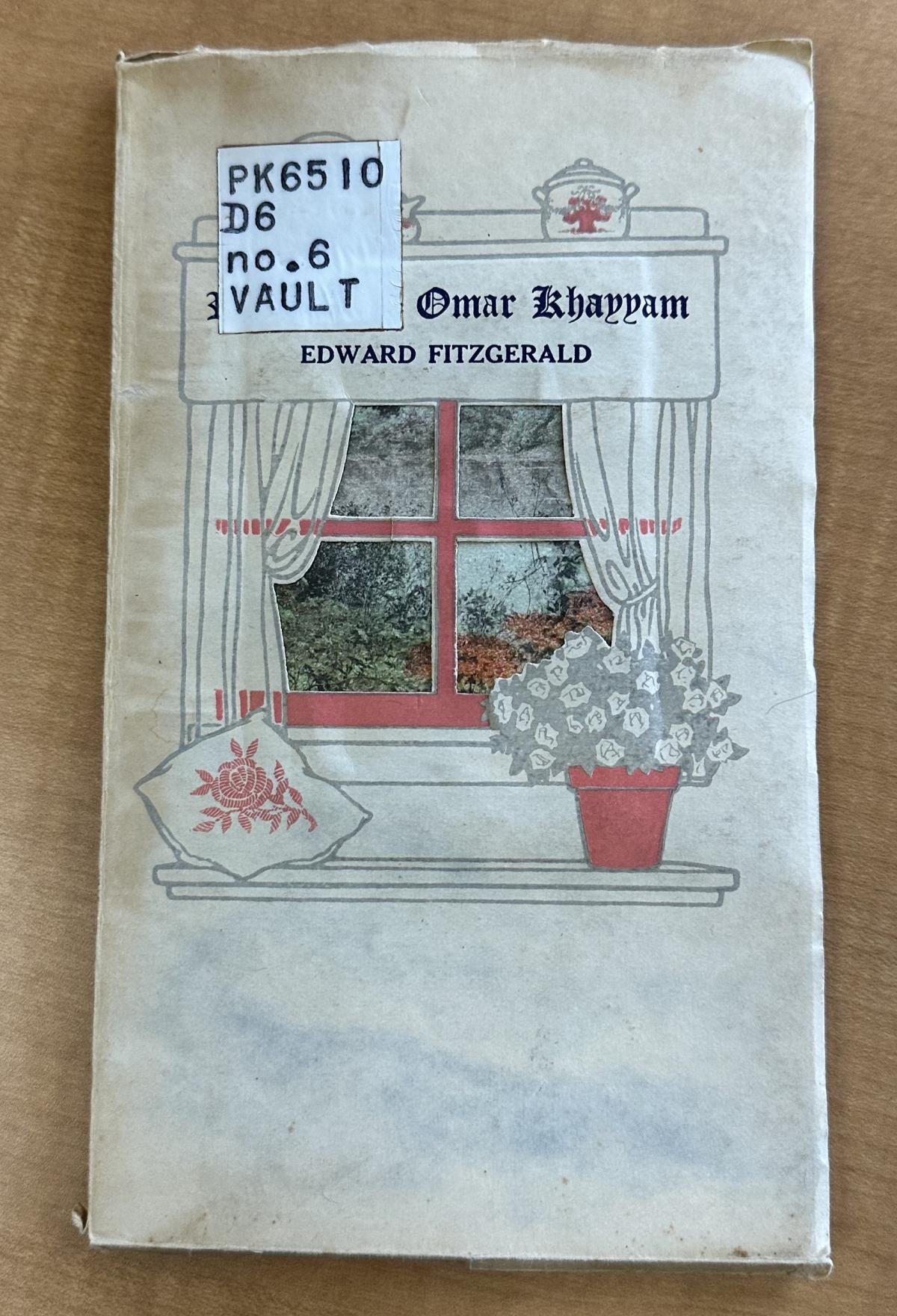

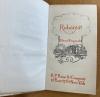

The edition of Fitzgerald’s Rubáiyát published by R.F. Fenno & Company sometime between 1900 and 1920 falls into a strange place in the conversation around gift book editions of the Rubáiyát and Orientalism. Black says when referring to the style and presentation of the gift books, “[The Rubáiyát] value becomes inseparable from its pretty, crafted, possessable diminutiveness. Khayyam’s verse remains entrenched in the categorically Oriental, in the land of seers and Eastern serenity” (61). However, this edition by R.F. Fenno curiously does not drape itself in the aesthetic that one would recognize as characteristically “Oriental”. Instead, the cover (see image 1) features a window looking out into an abstract environment, with cushions and vases decorating the window ledge. Rather than invoking the East, it invokes an almost British sensibility. The interior graphics as well keep this theme, with plates, books, and candles, all presented in a standard Western style (see images 2 & 3). The only graphic element that signals that this is a work from a non-Western perspective is the front matter page. It features a custom-made typography of the “Rubáiyát” in a font that is “Farsi-esque” (image 2). This is the singular visual component that hints at the origins of the work. Black’s argument regarding the nature of the gift book and the Rubáiyát does not seem to apply here as the visual markers that would make the piece possessable or like a jewel do not exist.

The actual text of the book, which includes bibliographic information about Fitzgerald, Omar Khayyám, and the several prefaces for the different editions, is printed with no other visual decor of any sort. The decorative elements of the book clash with the actual content of the text in such a way that it is almost dissonant. Based on the publisher’s, R.F. Fenno & Company, records of publication, and the distinct and custom typography of the title, this does not appear to be the first time R. F. Fenno & Company published a gift-book version of the Rubáiyát. The actual text of the book appears to have been printed sometime in the 1880s, but the frontmatter and cover appear to have been printed in the 1900 and 1920. It seems that the publisher through together the plates of the Rubáiyát and whatever dingbat they had on hand and created this mishap of an edition. This places it in a curious position regarding its role in Black’s conversation about the Rubáiyát and Orientalism.

The parts of Black’s argument that she makes about Fitzgerald’s translation naturally still apply, but in terms of the gift book, this edition seems to refute Black. While the visual components of this edition may serve as almost an erasure of the non-Western origins of the text, it does not sell itself on being possessable as a rare artifact the way Black describes. Rather, this gift book edition feels quaint with cottage imagery. It could be argued that this edition, rather than playing into Orientalism, engages in some sort of cultural appropriation with its visual elements. While the intentions behind the decorative elements are unknown, it is possible to imagine a publisher playing down a text's origins to try and market it to a Western audience. Rather than selling itself as a rare, but superficial beauty, to be collected, this edition minimizes the Persian origin.