Barbara Black’s On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums speaks at length about the influence of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam as gift books, and their appearance extravagant, exotic, and worth as much to own as to read. Black argues that this has roots in Orientalism, citing the Victorian obsession with misrepresentation of ‘The East’ for Imperial values as “the poem’s problematic status in a museum culture”(60). For Black, the gilding and pocket-sizing of the Rubaiyat demonstrate its objectification in many ways. It is valued as a pretty physical object to own, rather than just to read: “This poem’s value becomes inseparable from its pretty, crafted, possessable diminutiveness(61). Khayyám’s words themselves have also been altered, she argues, to fit FitzGerald’s Victorian sensibilities and fascination with Persian studies. Bitingly, Black refers to this as “in minstrel-show fashion, first dressing the Persian in English guise and then demanding a Persian “impersonation”(64).

The problem with applying this line of thinking to In A Persian Garden, however, is that the song cycle is not really a gift book. Its broad pages are far from conveniently pocket sized, its internal pages feature no illustrations to speak of, and it certainly has not been leaved in gold. The lyrics are as readable as any sample of FitzGerald’s translation, to an average American audience, but the music that comes with them is not something as universal. Some hundred and three years after this edition was published, we can say with fair certainty that it was not intended as a pretty object, but as something to be performed. That does not mean that Black’s argument is invalid in this case, necessarily, but rather that In A Persian Garden exists as an effect of the effect Black is noticing. A song performance, in this case, can be read as a gift from performer to audience, and the flourish of its composition as it is embellishments.

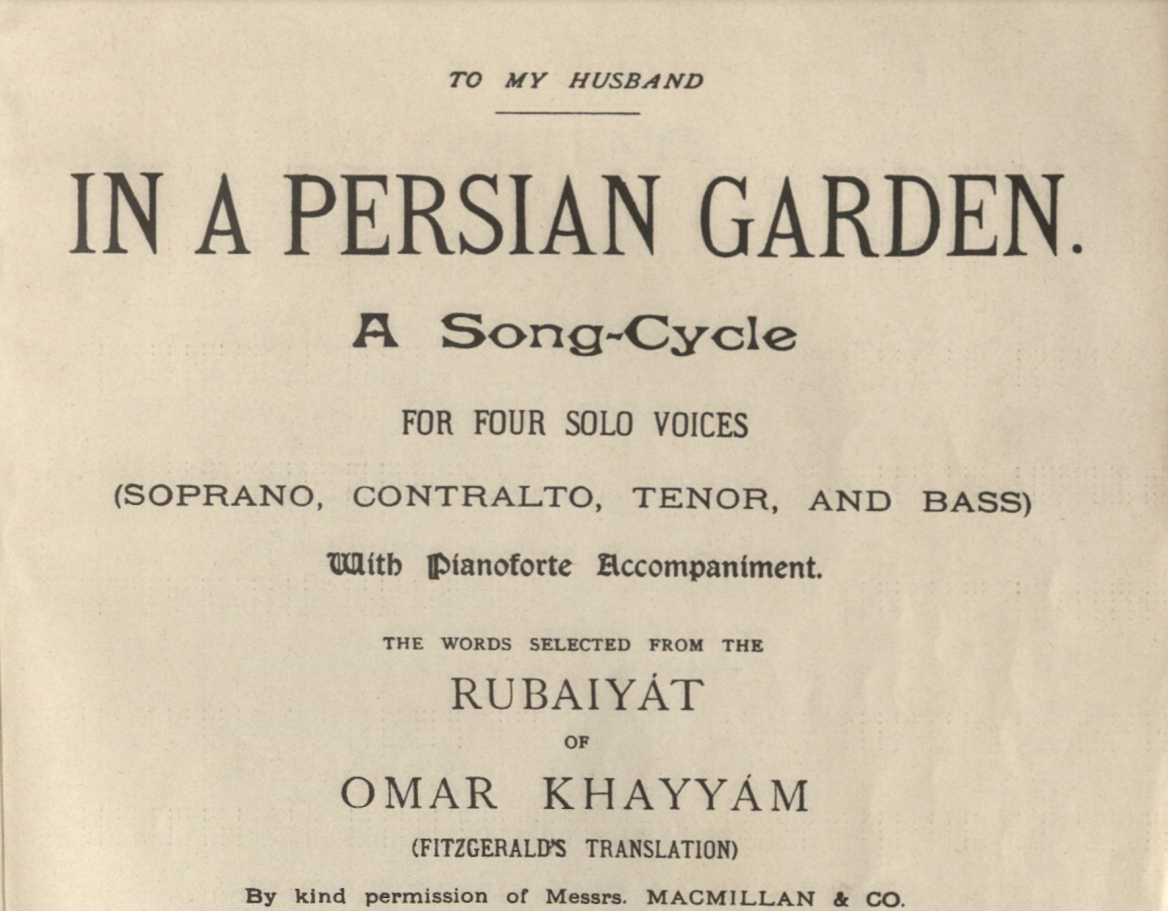

The copyright page of In A Persian Garden is the first clue to this: at the top, In A Persian Garden is dedicated “To My Husband”(see exhibit 1) This selection from the Rubaiyat exists as a continuation of its gift status, intentionally on the behalf of composer Liza Lehmann or not. Also on this page, obviously, is the title. Lehmann intentionally elected not to call this song-cycle Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, but something simpler and more related to an aesthetic. While it is true that the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam features a Persian garden prominently within its numerous quatrains (in the fourth edition, which Lehmann references, there are more than a hundred), it is not the focus entirely of the poem, or even Fitzgerald’s focus. Calling forth the image of a garden allows Lehmann to call on the aesthetics that Black argues formed the English and American popularity of Fitzgerald’s translation. It could be argued this is also a greater step away from the original contribution and intention of the quatrains of Omar Khayyam, redirecting from a famous astrologer to a more widely recognizable image.

From within the first page, there are the lyrics without music, to be reviewed on their own, or shared with an audience. In this edition, these lyrics are replicated inside the programme of a specific production in Madison, Wisconsin 1905. Lehmann has selected from the entire fourth edition by FitzGerald and transformed it into thirty-three parts for solo or quartet performance. We can see that the verses chosen are laden in imagery and luxury, and of course, gardens! (See Exhibit 2) We see, also, the re-introduction of Persian culture to an American audience. “True Dawn” is referred to as “a well-known phenomenon in the East, ” demonstrating the exoticism expected when this song is performed, “Iram” is defined as a garden but not King Shaddad.

These details support the claims of Black's thesis, in a roundabout way. In A Persian Garden's follows in the Orientalim applied to gift books of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam.