It can be difficult to understand the long and storied history of The Rubáiyat of Omar Khayyàm. Barbara Black offers a lens to understand the publication history through. A selection of Barbara Black’s work, On Exhibit, covers the publishing history of Fitgerald’s translation of the Rubáiyát. This includes its extensive history as a gift book. Black describes how the gift book decorations contributed to making the Rubáiyát a “compelling curiosity” to the Western world (Black, 60). Black points out that the language used to describe the Rubáiyát inherently makes it seem exotic. She also argues that “the poem’s value becomes inseparable from its pretty, crafted, possessable diminutiveness" (Black 61). Black is arguing that the actual text of the Rubáiyát is now intertwined with its gift book editions. Black also touches on Fitzgerald’s translation, writing “In certain ways, FitzGerald was determined to give an oriental flavor to his Rubáiyát, evident in his inclusion of an erudite footnote early in the text, in his use of Persian names in Stanza 10…” (Black 63). Black’s points in On Exhibit show how Orientalism and exoticism have impacted the history of the Rubáiyát in the Western world.

This gallery examines this edition of The Rubáiyat of Omar Khayyàm through the lens of Black’s claims. Three pieces of evidence from this edition will demonstrate Black’s claims surrounding the publication of the Rubáiyát. This edition is intended for use much more than it is intended for aesthetic, the way many gift books in this collection are. The edition contains both the score and a program from when the piece was performed. The score itself largely refutes Black’s argument because it is intended for use and does not fall into the gift book category that does display Black’s claims. The only parts of the score that could be considered to display Black’s arguments are the cover of the score, the use of Fitzgerald’s translation in the score, and the concert program.

The first piece of evidence is that the score itself is largely only for use. The cover of the score contains artwork by Edward B. Edwards, a white man known for his graphic arts for magazine covers and score covers. Edwards was known for his Celtic, Byzantine, Gothic, Renaissance, and Egyptian style artwork. The artwork on the cover frames the title and information of the score. The bottom half of the artwork is yellow and blue pillars, while the top half of the artwork contains a flower design with yellow and blue. The artwork on the cover could be considered vaguely Persian, in regard to the flower pattern on the top half of the cover. (See Figure 1) There are no illustrations in the score outside of the front cover.

The second piece of evidence is the score also fundamentally displays a kind of appropriated and Westernized idea of Persian culture in the use of Fitzgerald’s translation. The design and composition of the score does not particularly contribute to the appropriation of Persian culture, but its source material of Fitzgerald’s translation does. The selected stanzas featured in the lyrics of the score are not particularly Persian. I think it could have been entirely possible to compose a score that selectively picked the stanzas that sound the most Non-Western, but this is not the case with Lehmann’s score. The score does not contain Stanza 10, which Black singles out to be an example of Fitzgerald giving the poem an “Oriental flavor” (Black 63). Interestingly, both the lyrics at the beginning of the score and the sheet music itself contain the footnotes featured in Fitzgerald’s translation. These footnotes are something that Black points specifically to in her argument. This can be seen in Figure 2, with the footnote reading “The ‘False Dawn’ Subhi Kazib, a transient light on the horizon about an hour before the Subhi sádik, or ‘True Dawn,’ a well-known Phenomenon in the East” (Lehmann 4). These footnotes in the translation are some of what Black argues gives the Rubáiyát its Oriental flavor (Black 63). While I think the footnotes can be relevant in the lyric portion of the score, it is much less relevant in the sheet music portion.

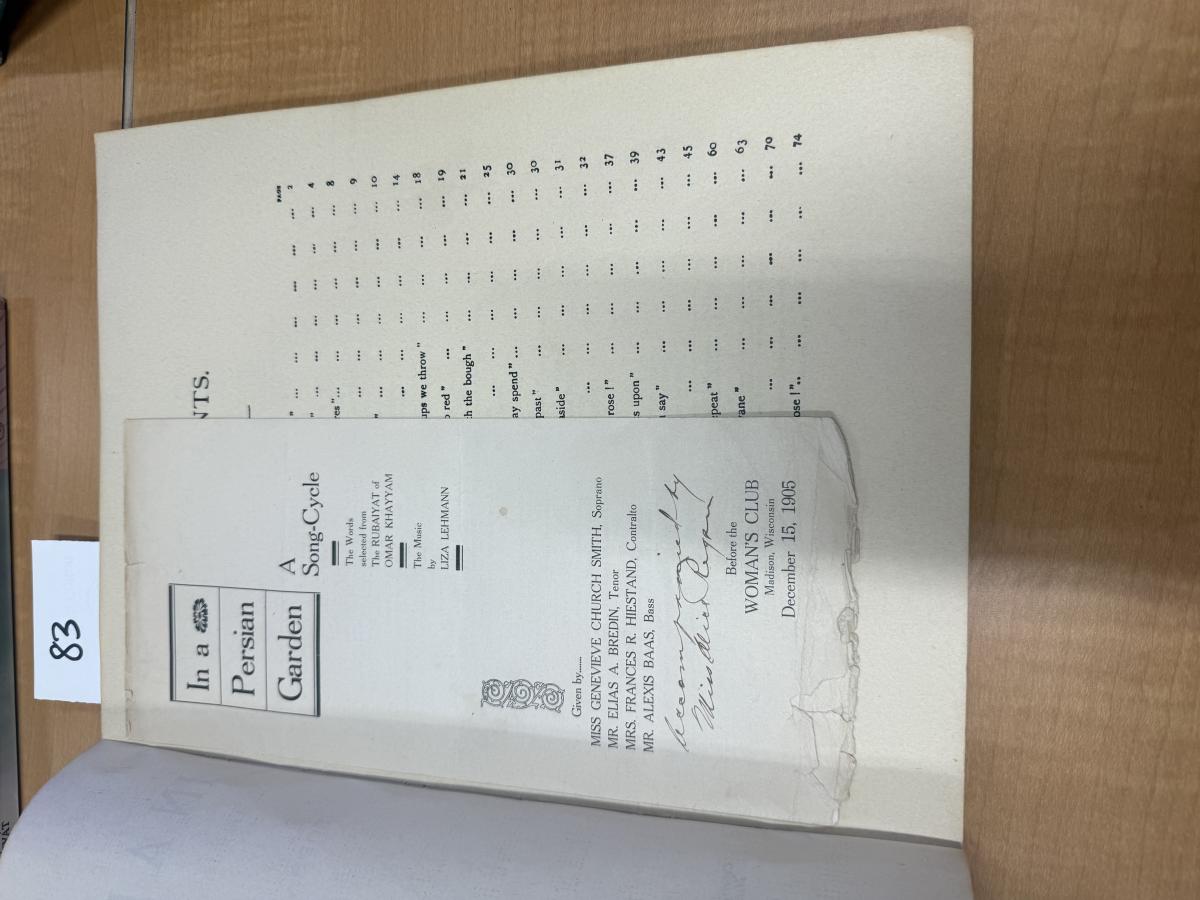

The third and final piece of evidence in this edition that is relevant to Black’s argument is the program that accompanies the score. The program contains the lyrics to the piece. The cover of the program (See Figure 3) has the information of the score that is also on the cover of the score/sheet music. At the bottom of the cover, there is a list of the singers from the performance. The program is from a performance in Madison, Wisconsin in 1905. The cover contains two small pieces of art, one a flower design by the title and another small nature inspired doodle above the name of the performers. These pieces of art seem to correlate more to the garden theme than any kind of Persian theme. The program is relevant to Black’s claims because of the audience for which it was performed. And although the Madison Woman’s Club did try to implement “diverse cultural programs,” this did not start until around 15 years later (Woman’s Building). It can be reasonably assumed that the audience for this performance was largely White. This fits into Black’s descriptions of the Rubáiyát in the Western world, and how it was often Westernized.

Lehmann, Liza. In a Persian Garden: A Song Cycle for Four Solo Voices (Soprano, Contralto, Tenor, and Bass). G. Schirmer, 1920, New York.

Black, Barbara J. On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums. United Kingdom, University Press of Virginia, 2000.

Edwards, Edward B. (1873-1948) – Welcome to Schoonover Studios -115 Years of American Illustration. https://schoonoverstudios.com/edwards-edward-b-1873-1948/.

Landmarks and Landmark Sites Nomination Form. Woman’s Building. City of Madison Landmarks Commission, 2004.