In On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums, Barbara Black explores the idea of appropriation that she believes has occurred through the growing popularity of Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. Black argues that “This poem’s value becomes inseparable from its pretty, crafted, possessable diminutiveness. Khayyám’s verse remains entrenched in the categorically Oriental, in the land of seers and Eastern serenity” (Black 61). In summary, because FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám gained extreme popularity as a gift book (something that can be collected, owned, and valued for superficial beauty), the poem itself has been appropriated. Ronald Balfour’s illustrated edition of Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám supports Black’s argument of appropriation by making the exotic more familiar through familiar references, dramatically Orientalist illustrations, and two competing illustrative styles.

Near the beginning of Ronald Balfour’s illustrated edition of Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, there is a stanza that uses a familiar Western reference to familiarize the exotic. It reads “Now the New Year reviving old / Desires, / Where the WHITE HAND OF MOSES / on the Bough / Puts out, and Jesus from the Ground / suspires” (FitzGerald, IV). There are no page numbers in this edition so I will be marking the page by the stanza title. On this page of the book, “the WHITE HAND OF MOSES” is capitalized and looks to be in almost a different font, see figure 1. This reference, borrowed from the Bible (Exodus 4:6), is possibly an attempt to make the poem more relatable and familiar to Western cultures. In the addition of this line, and its emphasis, not as a factor Orientalism, but as a sign of whitewashing. "Whitewashing" is an idea that mainly focuses on cinema, and the idea of casting white actors in roles that were intended for people of color. This applies to stanza IV because the capitalization and formatting emphasizes the familiar part of an unfamiliar culture. This stanzas supports Black’s idea that in its popularity and translation, the Rubáiyát gift books have become a way to appropriate Persian culture through the familiarization of the exotic.

In addition, the illustrations in this edition support Black’s idea of appropriation. On one of the pages of Ronald Balfour’s illustrated edition of Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, there is an illustration of a orientally dressed man and two women, one who is fully naked besides a pair of heels, and another who is clothed in draping cloth and has her breasts exposed, see figure 2. In this illustration, one of the women is holding a container that is emitting mystical smoke, while the other is pulling back a curtain, revealing the scene. The smoke is interesting to me, as it gives the stereotypical idea of mysticalness and incense that is often aligned with Middle Eastern cultures. The pulling back of the curtain gives the air of a production, or performance that is being put on by the subjects. It is also interesting to note that the naked woman pulling back the curtain has red lips, which is the only color to be found on the page. I interpret this choice to represent a Western view on Persian culture and how it is displayed for Western entertainment. The dramatic incense also supports the idea of appropriation as it is used to create a scenic environment for the pure source of Western readers entertainment. These images and their details support Black’s argument by accentuating the exoticness,

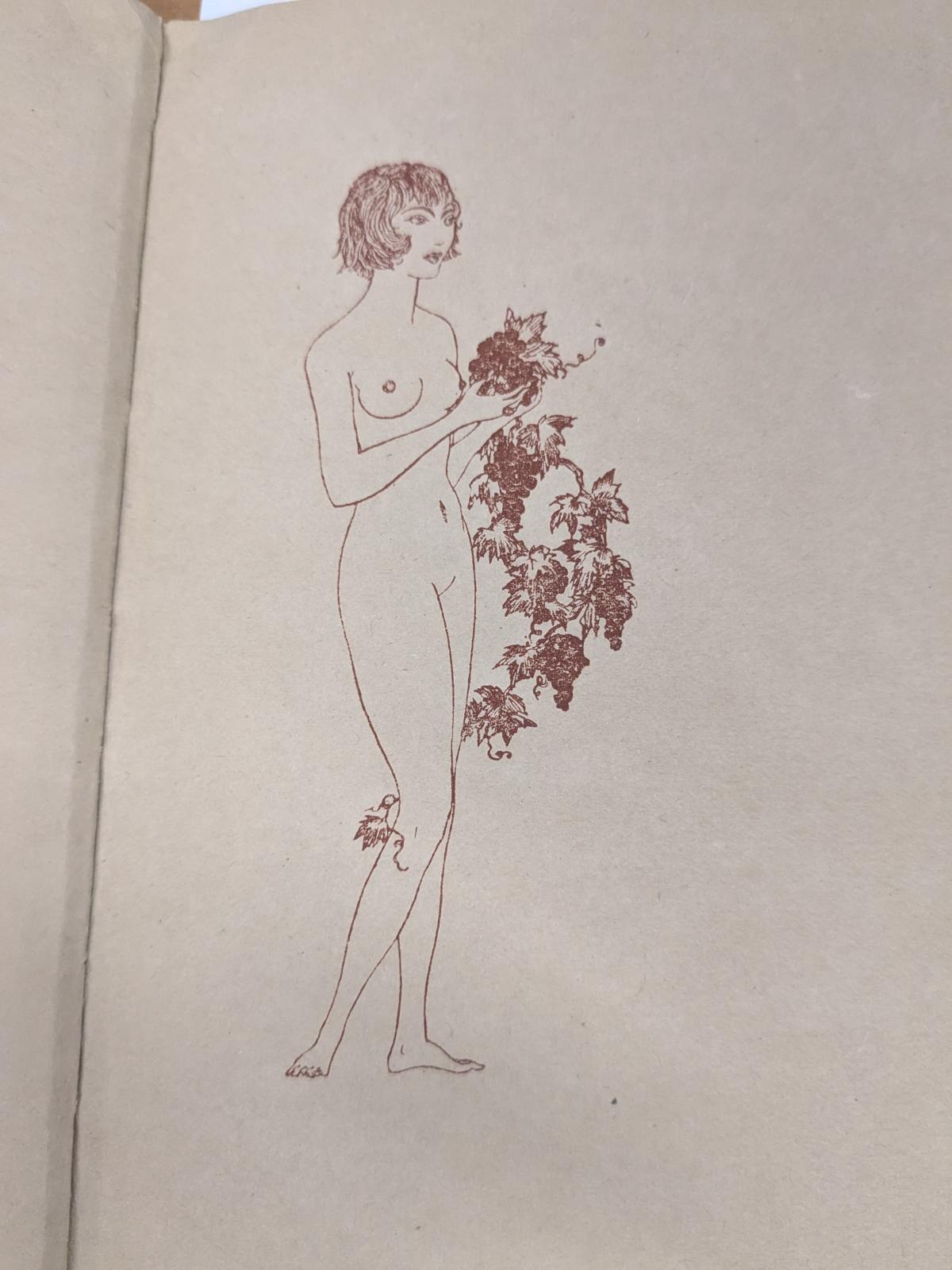

In this edition of Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, there are also multiple styles of illustrations that support Black’s argument of the appropriation of Persian culture through the attempt to make figures familiar. Ronald Balfour (the illustrator) employs two distinct styles. One style, as shown in figure 2, appears Orientalist and exaggerates the foreignness of the poem through dramatic faces, colors, clothing, and atmosphere. The other style is simple line work that focuses on naked women completing various tasks, see figure 3. Because the women are unclothed in this second style, and there are no background details, it is harder to connect the illustrations to a distinct Persian style. In addition, the faces are drawn in a very Western style and have almost a Hollywood feel with thin eyebrows, thick lips, and dark eyeliner. I have yet to decide if the Westernization of these women that are supposedly Persian displays or refutes Black’s argument about Rubáiyát gift books being orientalist. On one hand, it could be argued that because Balfour has drawn these naked figures with Western makeup, he is choosing to sexualize Western women instead of Persian women. On the other, and most likely, hand, changing the illustraition’s features to match those considered desirable in Western culture shows an extreme appropriation of Persian appearance and distinct culture. I believe that this is shown because it implies that Western beauty standards are more desirable than Persian beauty, thus lowering and reducing it. These two styles and the fact that they are separated supports Black’s arguments of the appropriation of Persian culture through the attempt to make figures familiar.

Overall, Ronald Balfour’s illustrated edition of Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám supports Black’s argument of appropriation by making the exotic more familiar through familiar references, dramatically Orientalist illustrations, and two competing illustrative styles.