Barbara Black argues in her book On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums that FitzGerald’s translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám and its subsequent popularity as a gift book and collector’s item are appropriations of the original text. She claims that the poem’s “talismanic value” (Black 60) comes from a combination of exoticization and colonization. On the exoticization side, FitzGerald’s translation of the Rubáiyát creates an image of a “land of seers and Eastern serenity” (Black 61) in which wine and women run aplenty. Black states that the translation colonizes the poem by making it relatable to its English audience, turning it into a “‘criticism of life’ not in some far-off country … but here and now” (Black 61). The Persian import becomes a highly-valued, collectible British export under the guise that “Omar sang to a half-barbarous province; FitzGerald to the world” (Black 61).

Black also claims that FitzGerald’s translation of the Rubáiyát is an Orientalization of the Oriental. By translating it to English and modifying the context to be more readily understood by English audiences, Fitz makes a poem that is “exotic without being foreign” (Black 64), allowing the English audience to fantasize about a life of free love and drink that was inaccessible yet tangible – it essentially “dress[ed] the Englishman in Persian costume” (Black 63) in a form of “Oriental drag” (Black 64). Alternatively, because the poem is in origin Persian, its translation becomes a form of minstrelsy, “Dressing the Persian in English guise and then demanding a Persian ‘impersonation’” (Black 64). Collecting prints of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám becomes a conquest, a way to hold power over the culture it caricatures.

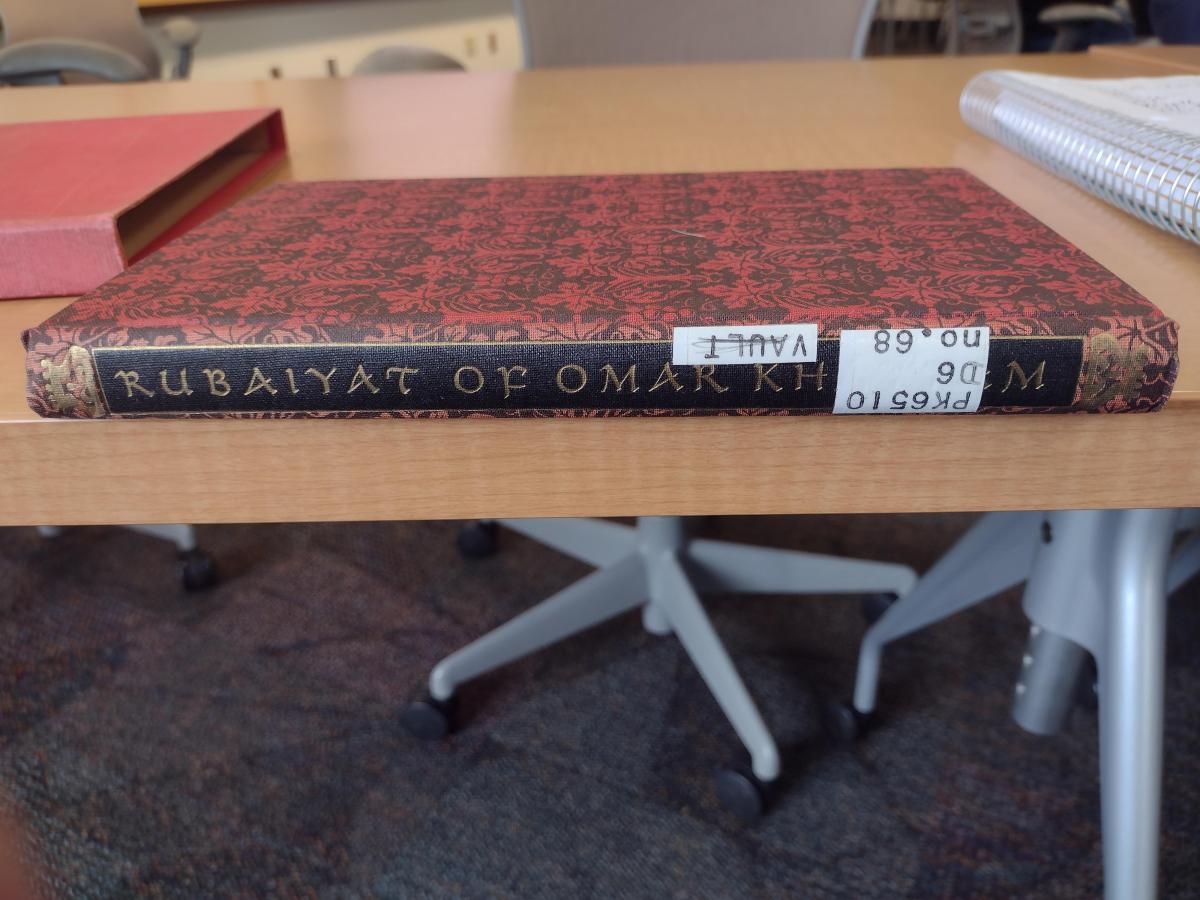

Although the phenomenon Black explores certainly exists on a large scale, whether any individual publication of the Rubáiyát exoticizes or colonizes the original text isn’t so black and white. For example, Black describes how many Rubáiyát gift books have “elaborately designed gilt covers” (Black 60) and “ornamental title pages” (Black 60). The 1947 Random House publication of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám presented here, however, is minimally decorated. It has a plain red cardboard slip case with no title or other indication of what book it is meant to contain. The cover of the book itself is a muted canvas, with a low-contrast grapevine filigree pattern on the front and back. Much like the slip case, neither the front or back of the book have its name, author, or other indication of what it contains. Only the spine has the title written in a muted gold paint (see image 1). The subdued nature of the book’s outside goes against Black’s description of an elaborate gold-leaf cover encrusted with stones and a miniature lock. However, there is an argument to be made that the vaguely Oriental-inspired typeface of the title on the spine, especially with the gold paint and the little bit of filigree decoration, may be meant to look good on a shelf, where only the spine of the book would be visible.

One of Black’s major critiques of the Rubáiyát as a gift book is that it is a form of “Oriental drag” (Black 64), in which the book mimics an “Oriental” style through its decorations and illustrations. The 1947 Random House publication avoids imitation by opting for the genuine. The artist for this publication, Mahmoud Sayah, is a classically trained Persian artist who got his degree in art from the University of Tehran. Although all of the illustrations in the book are in a Persian style, it isn’t an imitation but rather a promotion of Persian art due to the nationality and training of the artist. The “The Artist” page at the end of the book goes so far as to promote Sayah’s up-and-coming book about “a stranger’s impressions of this country” (Rubáiyát 149) – his experience living in America as a foreigner.

Though the promotion of a Persian artist gives this publication some benefit of the doubt as to whether it is Orientalist or not, the content of the illustrations themselves are in a grey area. The characters they depict are dressed in traditional garb and don’t fall into the Orientalist trap of drawing scantily clad women. However, the illustrations don’t correlate with the verses they are placed next to, and instead depict mostly one of two things: a man in physical contact with at least one woman near to a bottle of wine (see image 2), or a man surrounded by clay pots (see image 3). This does seem to push the narrative of a faraway land of women and wine, made exotic by the non-Western style of art.

The one aspect of the 1947 publication that leaves room for little benefit of the doubt is the preface, written by poet Louis Untermeyer (see image 4). The preface sings FitzGerald’s praises in a way that is very reminiscent of Black’s quotation, “Omar sang to a half-barbarous province; FitzGerald to the world” (Black 61). Untermeyer calls FitzGerald the “dabbler in the exotic who restored Omar to life” (Rubáiyát viii). He asks, “How much of the magic of the Rubáiyát is due to Omar and how much is due to FitzGerald?” (Rubáiyát xiv) and comes to the conclusion that “the Englishman took a haphazard collection of isolated bits and made [a] mosaic” (Rubáiyát xiv-xv). Although Untermeyer’s intentions may have been positive, his preface comes across as diminishing Khayyám’s contribution to his own poem and claiming FitzGerald as the primary cause of the Rubáiyát’s beauty.

Black, Barbara J. On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums. University of Virginia Press, 2000.

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. Random House, INC., 1947.