Barbara Black makes an argument that the continued collection, translation, gifting, and redesign of The Rubáiyát reflects Orientalist tendencies. One of the biggest ways this happens is with the idea of ownership and power imbalance. In this situation, the power is given entirely to the West, those who are distributing and setting the stage for this collection. The west was completely in control of this book and the translations that it chose to distribute to its people. The west wanted to hold power over the interpretation(s) of the information in The Rubáiyát. They make the narrative their own, and by doing this, they control the story, and they control how it is used. Black says, “The alien tongue has become the domestic word; the Persian imports has yielded one of Britain’s greatest exports to the world.” (Black, 61). The Rubáiyát specifically became a symbol of status, a collector’s item, and it began to erase the art. People did not always buy the Rubáiyát to read it, to enjoy it, or to respect it. People bought The Rubáiyát to impress people they care about, to give a beautiful gift, to pass down wealth. By owning and distributing The Rubáiyát people, or countries, are able to gain a very specific sort of status over it, and over the culture it represents. They are able to distort it and manipulate it to make themselves look better, and to give themselves wealth.

The debate of Orientalist or not is not as simple as it may seem. There are a lot of factors like intention that can skew what was thought to be a black or white decision. At the same time, it can be argued that intention does not matter if the action is Orientalist. I believe that this edition of The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam is not participating in the Orientalist trends that many of its brother and sisters are. I also don’t believe that this specific edition is contributing directly to a power imbalance. In this case, it seems like intention outweighs action. There are a few ways that this edition goes against the points made my Black in “On Exhibit”. The decoration, lack of personalization, and the quality of the book, lead me to believe that this book was given with the intent to be respected, to be used, and to be appreciated for its content.

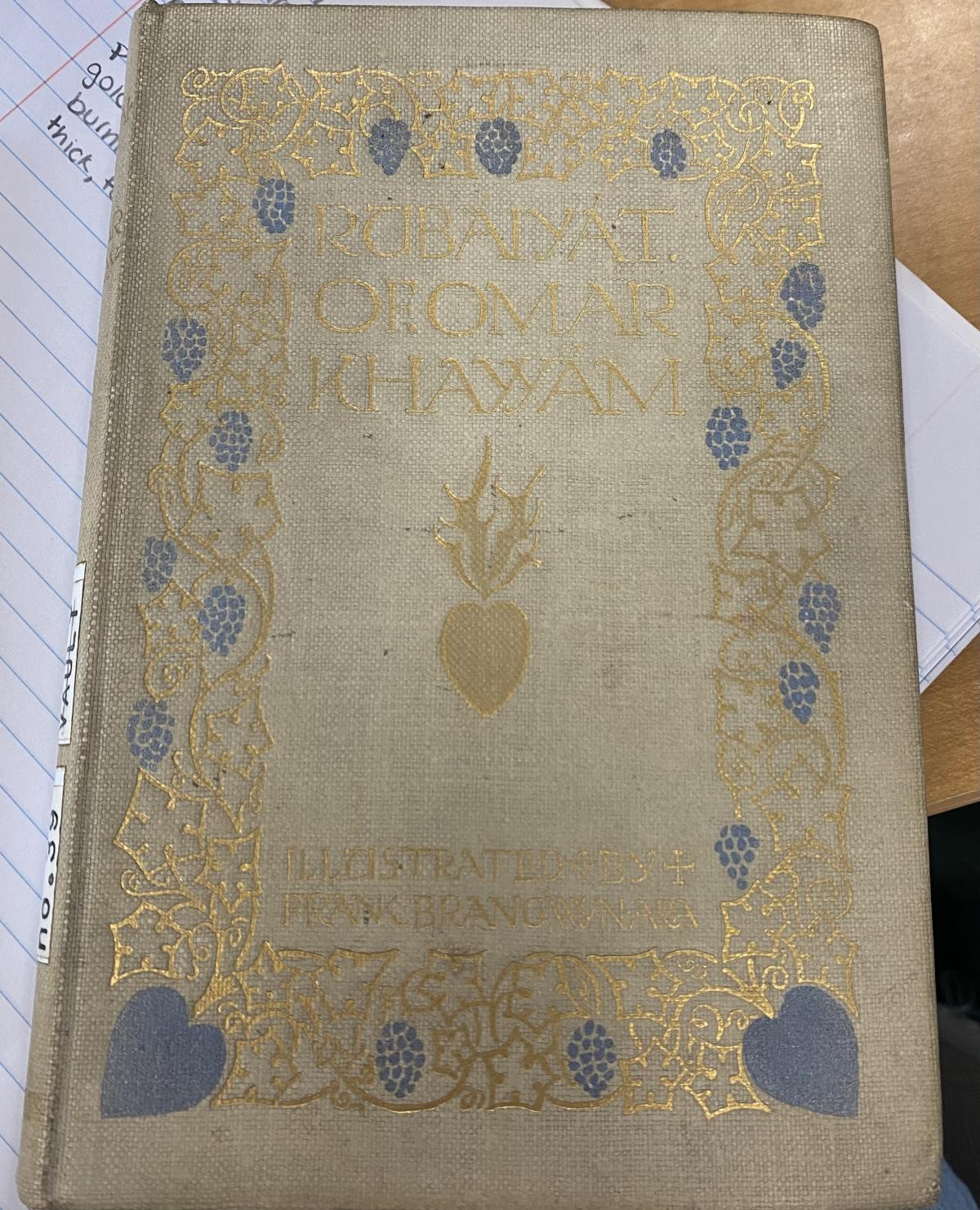

First let’s look at the decoration of this edition. In a lot of cases with the Rubáiyát, they were decorated with gems and engravings and illustrations. They were made to be flashy, to be a spectacle, and to be looked at. These were a few of the ways that they were connected to Orientalism. They were supposed to be a symbol of wealth, showing off the decorated covers and pages. The more decorated, the more expensive it was, and the higher your status became. In this edition of the Rubáiyát, there is some engraving on the cover, gold leaves with purple accents. However, it does not look expensive, it does not look glamourous compared to some of the other editions. The design is very basic, simple, it does not require an audience. The gold shapes actually fade on the tan cover, making them even less prominent (See figure 1.). On the inside of the pages, there is the same border of leaves, grapes, and hearts. While the color has become more contrasting, it is very clear that the words are the center of attention on these pages. The border is basic, and it is repeated on every page, so it is not commanding a lot of attention. There are only two other examples of decoration in this edition, and it is the inside of the covers. There is a cityscape stamped on the page (See figure 2.), on a purple background. It is a calm scene, there is not a lot to pick out or to display. The decoration in this book do not claim ownership over a culture or group. They are neutral, simple, timeless. Both the decorations and the illustrations leave so much space for the poem itself.

On the vein of decoration, the illustrations also help build the story of this book and its intentions. There are five illustrations in this edition, each a small rectangle cut out and glued to its own page. Each page also has its own protection page, a thin sheet of paper to keep the ink from the next page from rubbing onto the photo. Something interesting is that it is never said what paintings of Brangwyn’s the clips are from. The only information we get with the pictures is a quote from the Rubáiyát that connects to that image. There was not any greed from the artist, Brangwyn was not trying to sell his paintings or sell himself. His work just fit so well into this version of the Rubáiyát, and he wanted to contribute to that. This goes against the idea of trying to gain control or power over someone. This edition seems to want to give the power back to the words. This is where it gets a bit more complicated because, this edition is a translation. Fitzgerald is praised with the creation of this edition, and the words that get that power are his and not the original writer. This is where we start to bleed over into Black’s idea that these works were an act of Orientalism, and where action sometimes outweighs intention.

Apart from decoration, something that stood out when looking at this edition was the quality of the book. It is not falling apart like some books from this time but, there are obvious signs of wear and tear. The pages have stains on them, and the edges of the book are torn and falling apart. The first thought may be that this book wasn’t the best taken care of but, it also means that it was used, it was loved. The Rubáiyát was made to be read, it was made to be enjoyed and to be thought about. This book was loved, and it was thought about. With many gift books that are given as a token or given as a symbol, they don’t get used. The Rubáiyát was printed countless times, with different editions and different decorations. Some of those editions were never opened. Some people owned this collection and never read a single line because, it was given to them with that intention. These copies fit exactly the mold that Black made for Orientalism. This edition however, I like to think, was enjoyed with a cup of coffee or tea nearby. The dark spots on the pages (See figures 3 and 4) are from drips off the mug, they are dirt from being read under the bough of a tree.