In Barbara Black’s On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums, Black outlines the ways in which Omar Khayyám’s Rubáiyát has been appropriated by Western audiences, beginning with Edward FitzGerald’s translation of the poem. Once FitzGerald’s translation started becoming popular, Black describes the creation of Omar Khayyám Clubs in England and America, where “members attended Persian dinners and displayed their collected Eastern exotica as well as their bejeweled, miniature copies of the Rubáiyát” (Black 60). In this way, the poem “remains entrenched in the categorically Oriental, in the land of seers and Eastern serenity” as it was objectified and overly “Orientalized” in its translation as well (61,63). For instance, Black notes that FitzGerald often incorrectly embellishes his translation of Khayyám’s poem. Even the way Western scholars at the time referred to Khayyám seems disrespectful — with John Hay, for example, calling him Omar, instead of his last name (61).

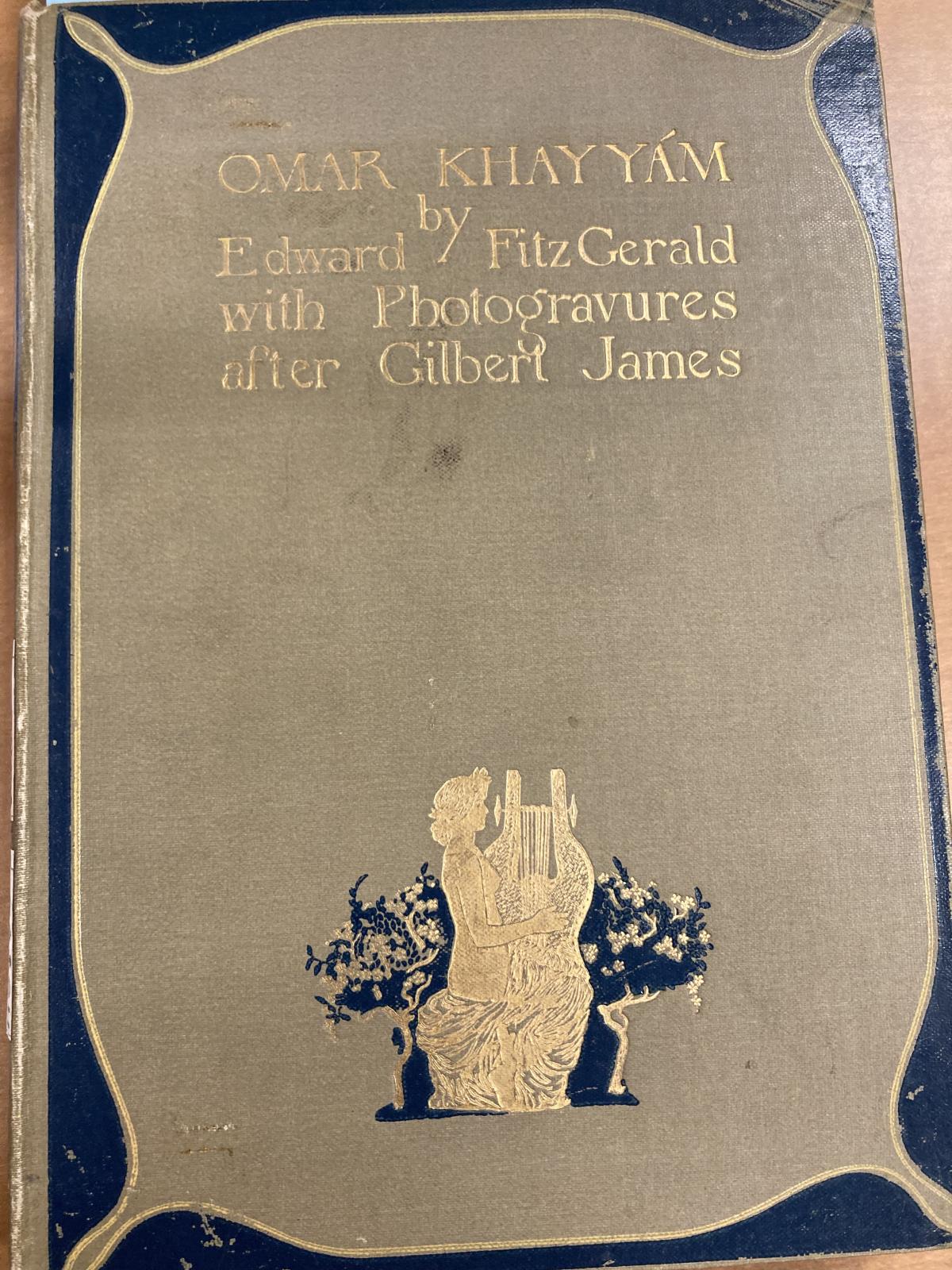

The 1905 edition of Edward FitzGerald’s translation of Omar Khayyám’s Rubáiyát confirms much of Black’s argument regarding the Orientalist gift books, with the inscription being the only aspect that truly suggests a minimizing and objectifying of the gift book — most of this edition seems generally appreciative of the poem. This edition contains gift book elements that emphasize superficial beauty and generic references to Persian culture, or what the West perceives it to be, at least. For instance, in Figure 1, the Orientalist aesthetic is clear, if subtle. The title and the curving, royal-looking border are both gilded as well, adding to a very beautiful cover. This aesthetic does not necessarily appropriate Persian culture or suggest Western superiority. If anything, this gilding seems to be part of an effort to appreciate the themes in the Rubáiyát, to emphasize the beauty of the poetry and nature. The illustration of a young woman playing the lyre, surrounded by flowers and greenery also does not seem overly exoticizing of culture, but rather another appreciation of the concepts running through the poem. She could represent someone enjoying music while in nature. This could potentially be an Islamic-influenced idea, referring to the use of devotional music in Sufism.

The personal inscription on the inside of the 1905 edition of FitzGerald’s translation, seen in Figure 2, is reminiscent of the rhetoric circulated in Omar Khayyám Clubs in England and America during the 1900s. This inscription, unlike the cover aesthetic, certainly suggests a power dynamic through the way the inscriber writes about Khayyám, and objectifies the Rubáiyát as a gift book. The writer is W. E. de B. Whiteaker, who is addressing and gifting the book to a Reverend E. H. Holden as a Christmas present in 1905. Like John Hay, Whiteaker also refers to Khayyám by his first name, beginning his note with “Salaam to Omar!” At the end of the note, Whiteaker repeats this, finishing with Salaam again. This is a very Islamic-influenced motif in the inscription, though not necessarily a sign of oppression or superiority on Whiteaker’s part, just a reference to Khayyám’s religious background that influenced the poem as a whole. However, addressing Khayyám by his first name seems disrespectful and even condescending, as during this time period, referring to someone’s first name would only be done if they were in a lesser position in society – a younger sibling perhaps, or a person of lower socioeconomic status. Calling him Omar maintains a strange Orientalist power dynamic, where Western audiences like Whiteaker and Holden enjoy and appreciate Khayyám’s poem but still refer to him in a demeaning tone. This inscription is one of the few aspects of this edition that definitively supports Black’s claim that the Rubáiyát gift books were often minimized and objectified by Western perception to maintain a power dynamic.

Gilbert James’ photogravures are displayed frequently throughout the book, often symbolizing specific quatrains from Khayyám’s Rubáiyát. One photogravure in particular illustrates a few Islamic, Persian, or vaguely Eastern-influenced motifs in its drawing style, and demonstrates how the gift book does not necessarily only seek to minimize the culture into something superficial and collectible. The photogravure features a man with a beard and turban, wearing a long skirt with the Star of David embroidered on it, with long black wings extended from either shoulder – like a dark angel. He has his arm around a woman who is wearing a long skirt, bracelets along her arm, a necklace around her neck, and a feathered headpiece on her head. She’s sipping from a cup filled with a dark liquid, eyes closed. Behind them is a vast landscape, mountains, and a bare tree. The scene seems to be representative of quatrain XLII, which states:

And lately, by the Tavern Door agape,

Came stealing through the Dusk an Angel Shape,

Bearing a vessel on his Shoulder; and

He bid me taste of it; and 'twas—the Grape!

This part of the poem describes an “angel shape” offering wine to someone, which is clearly shown in this photogravure. The image is certainly influenced by Persian culture, with the turban, bracelets, and Stars of David giving a very “Eastern” aesthetic. Like the rest of the photogravures, this does not seem to reduce the culture or demean it, but appears to be a sincere effort to capture the essence of the Rubáiyát.

Works Cited

Black, Barbara J. On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums. United Kingdom, University Press of Virginia, 2000.

FitzGerald, Edward, translator. Omar Khayyam by Edward FitzGerald with Photogravures after Gilbert James. London, United Kingdom, George Routledge and Sons, 1905.