In On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums, Barbara Black argues Omar Khayyám’s Rubáiyát has been Orientalized and appropriated in Fitzgerald’s translation and its distribution as a gift book. There’s a couple ways people have done this that Black argues. One of the main ways is through this idea of Orientalization. Orientalism is a Western invention that imagines the East as exotic, sensual, feminine, submissive and so on. In other words, it fetishizes Eastern cultures and depicts them as something for the West to conquer. When talking about the importance placed on owning the text over actually reading it, Black states, “The thrill involved in possession is consistent with the rhetoric of conquest that characterizes this text’s existence in the West” (61 Black). This connects to the decorations that make some editions gift books, the collectivist museum culture Fitzgerald’s translation possesses, and the way the East is depicted in the illustrations and the verse. Another way Khayyám’s Rubáiyát has been appropriated is, “by de-emphasizing its otherness and focusing instead on the familiarity” (61 Black). In other words, some critics have instead westernized the text, and stripped it of any cultural context or background. Which is where my edition seems to lie.

Though Black’s argument does hold a lot of truth for many editions and translations, when talking about my edition of Khayyám’s Rubáiyát, I do not think all gift books are Orientalist. However, I do agree with Black in that gift books, including my edition, do appropriate the original and its culture Khayyám was writing from. The three main reasons I am going to explore include: the lack of recognition for Khayyám’s original text, its comedic form, and the non-existent depiction of Persian culture.

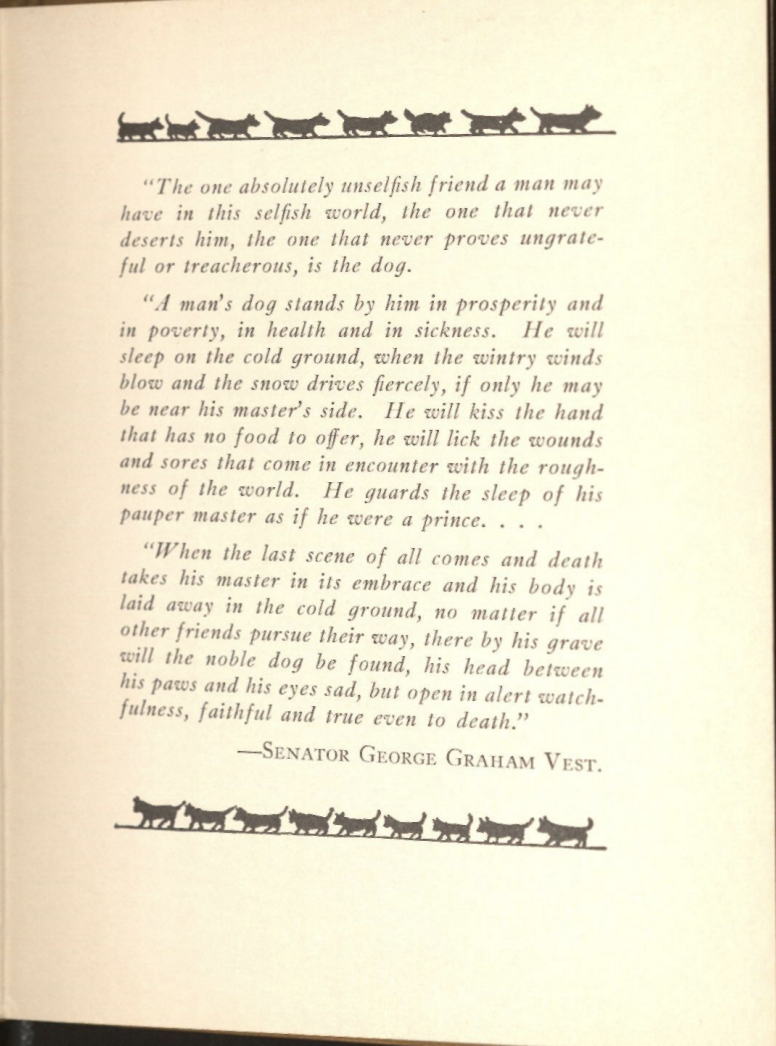

The first point of note is the information Collins decided to provide at the front of the text. On the cover, all the reader is given is the title, The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Terrier, and an illustration of the main character, the Scotch Terrier (a breed of dog now known as Scottish Terrier). The spine also only contains the title with no other information. When you open the book to the second title page, we get more information including the author’s name and the publisher. However, as one can notice, there is no translator name or credit given to Omar Khayyám. This lack of recognition is one way Collins strips the Rubáiyát from its originating culture. This is because it doesn’t give Khayyám credit and without this or having at least a translator’s name, the reader may never know the original was written in a different language. Another piece I’d like to note is the recognition Collins does choose to supply the reader with. The page before the first stanza is a quote from Senator George Graham Vest (see image 1). Vest was a Senator for 24 years in the U.S. and served on the Confederate Congress during the Civil War (Robert). Considering what we know about the Confederacy and the Civil War, I found this very surprising for the only recognition to be this Senator. Him being apart of the United States' government completely takes the text out of its Persian roots and Americanizes it as well. Though in the context of the book it makes sense, I was still surprised nonetheless. This however is not to say that it is Orientalist, instead it is appropriative due to the lack of Persian representation.

Another note to make is the way the illustrations depict the text and its subjects. One big point Black makes is the way gift books push the Orientalist narrative that the East is exotic, sensual, erotic, etc.. She describes, “Khayyám’s verse remains entrenched in the categorically Oriental, in the land of seers and Eastern serenity” (61 Black). This was also something we discussed in class: how the illustrations and dialogue depict Middle Eastern (specifically Persia here) people and culture as these ideals. Which is why I don’t think this edition is Orientalist, because none of the illustrations depict Persian culture. All of the humans in the illustrations have European or American fashion and clothing, which was my first clue because there are no people depicted from this culture. Therefore, there is no commentation on the culture at all (see images 2, 5-7). The interiors in every drawing seem to be from a European or American household as well. They have some key Victorian style details that suggest this like the crown molding, the feet and legs of the piano and bench (see image 3), and the ornate floral patterns.

My last main point is the format of the text itself. This edition is a parody and is comedic at its core. Though this aspect is possibly appropriative, it is not Orientalist because it’s not actively dismissing Khayyám’s original text. Parodies can be very satirical and thus critical of the subject, however I argue that this parody is not satirical in that manner. As Khayyám’s Rubáiyát discusses his deepest desires and philosophies of life, this edition discusses a dog’s personal desires and beliefs. His desires include things like food, meeting other dogs, receiving love from his owner, going on walks and all other wants one can think a dog might have. The humor is centered around how silly the dog is and thinking about what a dog’s deepest desires are (see image 4). If the humor directly made jabs at Khayyám, his philosophy, or Persian culture I would feel differently. However, the language is positive, uplifting and purely from the perspective of a dog who does not seem to have the capabilities of political or malicious thoughts.

Works Cited:

Black, Barbara J. On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums. University Press of Virginia, 2000.

Collins, Sewell. The Rubáiyát of a Scotch Terrier. Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1926.

Robert C. Byrd, The Senate, 1789-1989: Classic Speeches, 1830-1993. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1994.