Created by Mira Batti on Mon, 05/01/2023 - 12:21

Description:

In the description, we had talked about how Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám had become a popular gifting book after FitzGerald’s first translation in the 1800s. There are many factors which cause it to become popular, but the one we’ll go over is called ‘Orientalism’. It is when Eastern Asian culture is described, mainly in a Western lens. Barbara Black explains this issue in her work, On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums: “Khayyám’s Rubáiyát became thoroughly objectified” (1). As far as translations go, there’s only so many exactly-the-same definition words in-between languages, so variety will happen- there’s nothing wrong with that; however, FitzGerald had been known to have his own agenda as an Englishman, translating a medieval Persian script. FitzGerald’s edition took many liberties, in which Taher-Kermani describes in their work, Persian Presence in Victorian Poetry: “he [FitzGerald] was simply not fond of Islam” (3). With these clear biases going into the translation, we can only infer that his intentions were not pure, but to push his agenda of anti-Islam. Yes, Khayyám had expressed their own doubts about the religion, that was the entire point of the Rubáiyát; however, we can all agree that FitzGerald is man who lived in England and had absolutely no idea what living in Persia was like and what it meant, culturally and religiously. In this instance, FitzGerald took this deep-dive of Persian culture clashing with Islam ideals, and decided to use it for his own personal gain and anti-Islam agenda. But I would have to disagree, to an extent, that my edition is not objectifying Rubáiyát, as much as which Black and Taher-Kermani have said about FitzGerald and the original.

Barbara Black’s argument is that the Khayyám’s Rubáiyát has become thoroughly objectified through FitzGerald’s translation. From gifting the Rubáiyát on holidays to having over 93 different editions of the piece, Black remarks that the Rubáiyát is not what it was meant to be. It has been taken from the East to serve a colonist perspective in the West, and that, ladies and gentleman, a great example of Orientalism. Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám served as a question of Islam, not against it, but wondering what does it mean for death and life and religion to coexist; however, ever since FitzGerald came along, the English translation serves to push against Islam idolization- which was never the perspective the original took on. The once philosophical book has been turned into a piece of propaganda against Islam: an object. Black’s consensus about Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám is true and only proves how Westernized history has become for the greater public and how Eastern history is but a gift book for Christmas.

But you know when you translate an English word to German, then back again, then to French and then to English? Yeah, it loses all its English semblance. That’s what happened here with Rubáiyát of Ohow Dryyam. From the 1100s to 1800s to 1900s, from Persia to England to America? There is no correlation between my edition to the original: there is no place where my edition drags against Islam, or serves as propaganda against a nation that has nothing to do with America. Rubáiyát of Ohow Dryyam is a purely American parody- as it only questions the American government’s choices against alcohol. As I said in the description, Rubáiyát of Ohow Dryyam has not only proved to honor the original, but make it meaningful in another context- in which art thrives by. Art is creative, it is inspired and it is transformative- that’s why copyright laws exist: that if someone transforms a piece enough, it is original; therefore, I would say that’s what the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám wanted to provoke: they wanted people to think about the powers that hold us in place as a society and community. Rubáiyát of Ohow Dryyam does just that by talking about the troubles of cold turkeying sobriety just because the government said so, it questions why alcohol would need to be banned if it caused such pain to the country.

Rubáiyát of Ohow Dryyam does not hold FitzGerald’s inherent bias; it’s so far removed from him as an author. And I’d like to add, there is not one mention of FitzGerald from front to back, but there are credits to Khayyám on the cover. Rubáiyát of Ohow Dryyam is closer to the 1100s original than that of an Englishman’s. It pushes an agenda against the American government for banning alcoholism and putting their citizens through withdrawal and hardships- a clear distinction from FitzGerald bias to push propaganda that Islam is bad, while sitting in an English office. Just as the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam was made by a Persian, for Persia, the Rubaiyat of Ohow Dryyam was made by an American, for America.

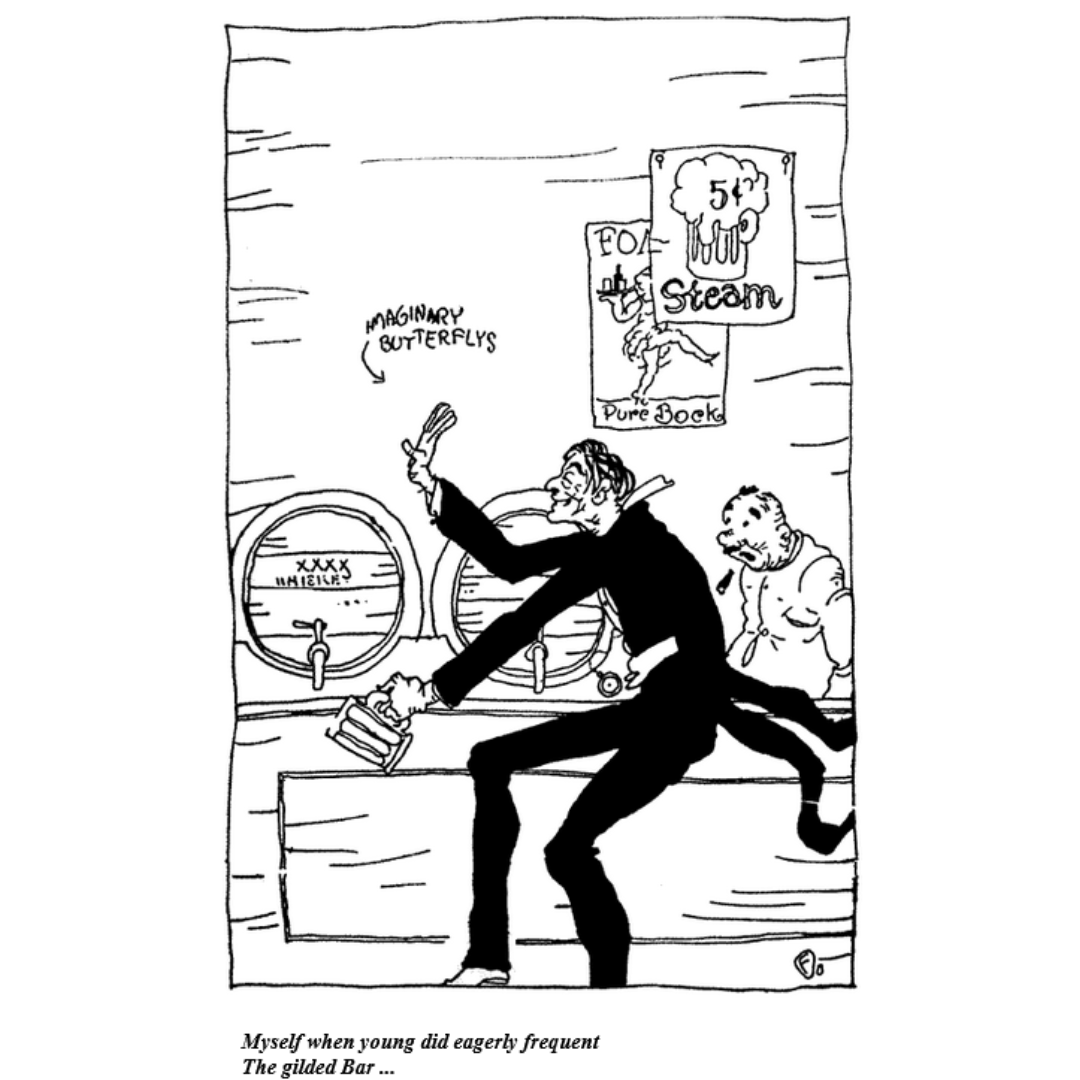

(See Figure 1, for an illustration of the speaker in the bars, where he frequented often- alcoholism)

The first reason why the Rubáiyát of Ohow Dryyam is not Orientalist: the completely American topic. FitzGerald speaks of Islam while as an Englishman himself, unable to fully grasp the culture, or religion, and instead, takes it upon himself to turn it into a biased account that fits his own will. FitzGerald’s edition is Orientalist, and it objectifies Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. He made it into a gift book to spread around- to make people not fully understand the contents of the philosophy since it’s just a gift book; he minimizes the struggles of Eastern culture, and dumbs-down Islam into an overbearing power- which none of it is true. However, Rubáiyát of Ohow Dryyam does not go over any of that: it never mentions Islam, or any depictions of Eastern culture. Orientalism is about taking aspects of Eastern culture and then painting for a Western perspective, but the only thing Rubáiyát of Ohow Dryyam took was it being a book. It took inspiration from the Rubáiyát, but no stanzas, or illustrations, attempt to depict Eastern culture. Therefore, I would say, it is not Orientalist.

The second reason: the author’s intent was not to belittle Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. Orientalism is based in oppression, meant to minimize Eastern culture into something that can be bought, and gifted. And yes, Rubáiyát of Ohow Dryyam inherently banks off of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám’s Western popularization- which was Orientalism at its finest, but I would argue that the parody is more attached to the original. It works by crediting the original over FitzGerald, so when people bought it, thinking of FitzGerld, the first name they see is the original author’s: Omar Khayyám. Rubáiyát of Ohow Dryyam is an edition in which transforms Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám into another art piece that serves as a question for America and its power. Just as religion was an issue present for Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám in Persian, and American, alcohol is its religion. Which is a cultural thing for America, and does not impede Eastern values and culture in a cherry-picking way.

(See Figure 2, for the cover page in which J.L. Duff apologizes to Omar)

Lastly, how do we really describe Orientalism? Because Rubáiyát of Ohow Dryyam only imitates the tone and structure/form of an Eastern piece, none of its aspects makes it inherently Eastern. If an author cannot even imitate structure and tone, in inspiration, then all art would be considered plagiarism and appropriated. And it is not considered that. As a world, as humans, we have seen art grow and weave through timelines, by the ability of artists to inspire and to be inspired. I do believe that Rubáiyát of Ohow Dryyam is art just like the original Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, whereas FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám is just propaganda against Islam, in the lens of the English.

(See Figure 3, for the first stanzas that show the inspiration of medieval English speech- which represents inspiration from the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám)

In conclusion, did the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám have illustrations? No, because, in its context, it didn’t need them. But Rubáiyát of Ohow Dryyam is a great example of using base material, and building upon it. J.L. Duft does not erase what the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám is as inspiration, but he does lend an Americanized lens onto it- as the story is based on American culture and issues. And the most important part: J.L. credits Khayyám, not FitzGerald.

Sources:

- Barbara Black (2000) On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums. https://www.google.com/books/edition/On_Exhibit/z19oXDrIrbEC?hl=en&gbpv=0

- J.L. Duff (1922) Rubaiyat of Ohow Dryyam. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/23338/pg23338-images.html

- Taher-Kermani (2020) Persian Presence in Victorian Poetry. https://books.google.com/books/about/Persian_Presence_in_Victorian_Poetry.html?id=06MxEAAAQBAJ&source=kp_book_description