In her book On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums, Barbara Black asserts that popular consumption of Edward FitzGerald's Rubáiyat of Omar Kháyyám, specifically within the context of its proliferation as a gift book, is inextricably tied to a materialistic "thrill involved in possession" reminiscent of colonialist mores (61). By "dressing the Persian in English guise and then demanding a Persian 'impersonation'," which Black finds evident in FitzGerald's footnotes indicating the use of Persian for "evocative effect rather than substantive meaning," the translation exposes itself as an Orientalist appropriation (63-4). Via physical elements such as "elaborately designed gilt covers and ornamental title pages," this objectification was furthered by publishers and reciprocated by collectors, who along with the critical establishment marveled at Fitzgerald's accomplishment in transposing the lyric of a 'barbarous' people onto a civilized context (60). The poem became relegated to a curiosity, a superficial stand-in for Persian culture, albeit one essential to the literary collector's conquest of the exotic. My particular edition displays the marks of the Orientalist dressing elaborated upon by Black in its physical denotations of ownership and a feebly self-conscious preface fixated on aesthetic appreciation over cross-cultural reckoning.

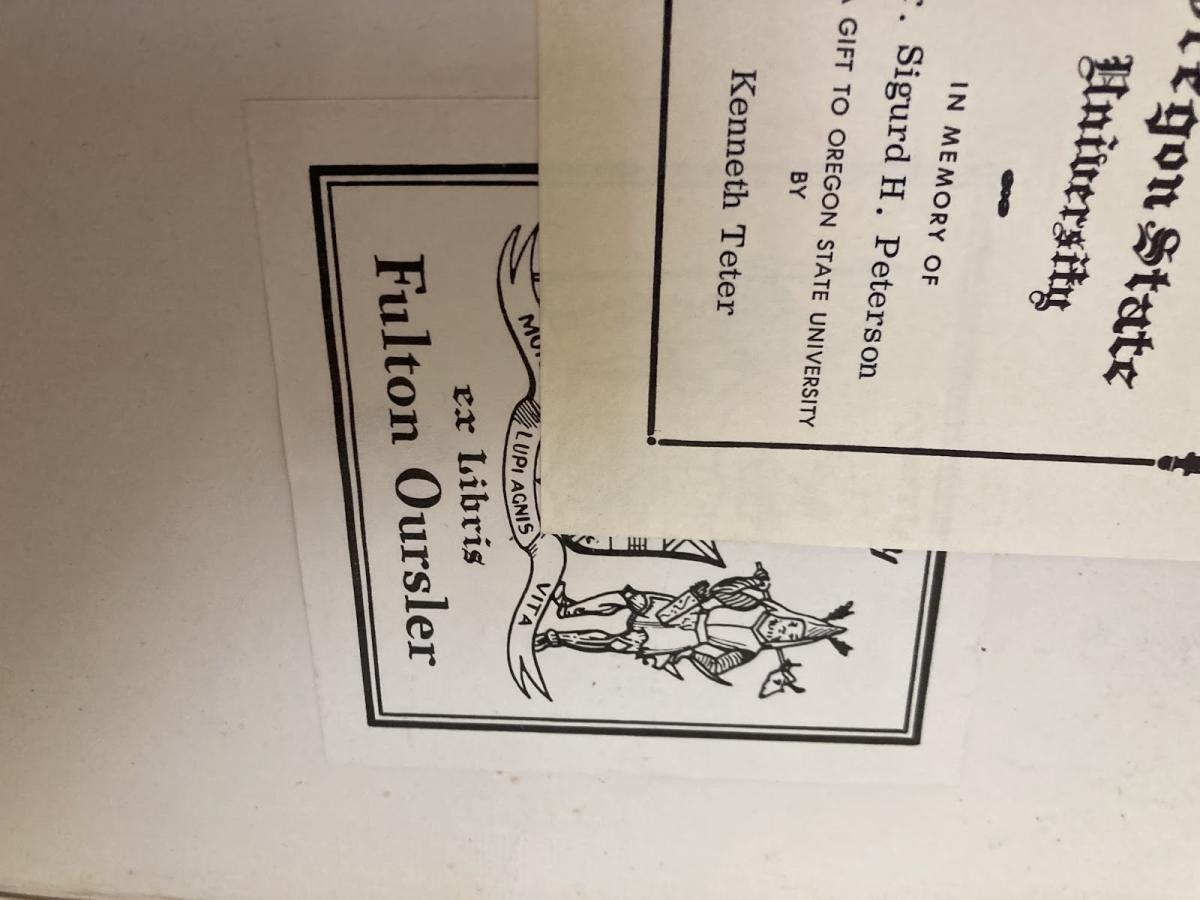

Said edition, gifted to Grace Perkins, bears several signifiers of a gift book, as described by Black. An internal inscription solidifies the volume as a Christmas gift, while the bookplate indicating its inclusion in a personal library suggests its placement in the home, member to a larger collection [See images 1 and 2]. Seeing as Perkins and the book's purported owner, Fulton Oursler, do not share a name, one must consider whether the edition was gifted out of Oursler's personal library into Perkins' possession, if the two engaged in an unmarried living arrangement within which a gift from Oursler simultaneously belonging to his collection would cohere, or if the book had passed hands into a third party's possession prior to being gifted. Unknowable as the specific context may be, the evident genealogy suggests that the edition’s original owner ensured its survival long enough to pass on to others, extending its lifespan in a way that jars with the poem’s nihilistic message (Black 62).

Perhaps, the publishing of and engagement with this text was intended on the grounds of education or appreciation of beauty. There is no further evidence of ownership that may provide a hint one way or another, barring a sketch scribbled onto page 121 [See image 3]. It depicts a human profile, with adornment possibly indicating it as a female's. Vaguely, the headdress/hairstyling resembles that of the unnamed woman, presumably personifying the lover of Kháyyám's poem, sprinkled throughout the edition's illustrations. The high level of detail in this doodle may indicate eager interest in Persian customs, knowledge of which are entirely simulated by the words and drawings of white men, centuries later. The drawing's inspiration could have arisen from interest in the superficial elements of the text, specifically artistic inserts which further an exotic, risque vision of the East consistent with Orientalism [See images 4 and 5].

A 31-page preface courtesy of Reynold Alleyne Nicholson, referred to as a lecturer in Persian at the University of Cambridge on the title page and later self-alluded to as a professor of Oriental studies, appears in lieu of FitzGerald's original introduction to Kháyyám. Nicholson's addition to the text begins on an educational bent, concerned with then-recent developments regarding authorship and acceptance of the generally unknowable life as led by Kháyyám and others of his time (Kháyyám 2) [See image 6]. Consistent with the embellishments which evince a "compelling curiosity," Nicholson ultimately expresses a wistful view of FitzGerald's transforming of "the scattered threads of the Persian original into one complete and imperishable masterpiece" (Black 60; Kháyyám 5). Nicholson's flattery appears to be in accordance with the power dynamic of Western superiority perpetated by his outmoded field of study. At the conclusion of his preface, the scholar indicates that he his notes are composed of words and lines which he has chosen to personally translate, out of the view that their meaning may be better elucidated with direct access to their original meaning unmediated by FitzGerald's concessions to rhyme and meter (Kháyyám 30) [See image 7]. If he truly valued Persian culture over the Western reinterpretation that he acknowledges the text to be, would Nicholson not have made the chief function of his text a rebuttal to its Orientalist skewing, rather than relegating these supplements to the fine print?

Trademark appeals to authenticity abound - gilded text, Persian-styled English font, bookending illustrations of natural beauty, and supplemental text provided by a professor of Oriental studies - within the Oursler-Perkins copy despite its relatively large size in contrast to the gifted version's traditionally miniature, 'collapsed' form (Black 61). The edition's supplemental text, penned by a self-professed expert on Orientalism, grants more concession to the commodification of the translation than is often the case, yet ultimately reveals itself as intent to romanticize the "understanding of that remote past;" an invented Persian culture neutered for the English public (Black 63).

Black, Barbara J. On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums. University Press of Virginia, 2000.

Khayyam, Omar. Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. Trans. Edward FitzGerald, R & R Publishing, date unknown.