In her book On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums, Barbara Black explores how the act of collecting shaped how the British saw and valued the world, especially places outside of Europe. One work she focuses on is Edward FitzGerald’s translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, Persian poetry that became extremely popular in the 19th century, which over time was published in many fancy editions and often illustrated and sold as gift books. Black argues that these versions, while beautiful, turned Khayyám’s poetry into an object, something to own and display rather than something to engage with deeply. “This poem’s value becomes inseparable from its pretty, crafted, possessable diminutiveness,” she writes (61). In other words, the Rubáiyát became more about its packaging than its cultural or poetic origins.

Looking at the 1951 edition published by Shakespeare House with illustrations by Edmund J. Sullivan, we can see how this trend continued into the 20th century, though slightly differently in this specific edition. On the one hand, the book still presents Khayyám’s poetry through a Western lens; on the other hand, it does so in a way that sometimes seems more thoughtful, or at least more serious, than earlier, flashier editions. This balance can be seen through three key pieces of evidence: the cover design, the translation itself, and the illustrations inside.

First and most uniquely, the cover gives us a lot to think about (see figure 1). Instead of being decorated with elaborate floral patterns, Persian calligraphy, or "exotic" imagery (as many other gift editions were), this edition has a plain cloth-bound cover with a maroon/reddish and black buckram spine and a simple gold star design. There is also a cameo of Shakespeare on the front, placing the book within a Western literary tradition, almost as if it’s saying, “this belongs here with the other English greats.” The cover makes the edition feel like a classic volume of poetry or philosophy, not something foreign or unfamiliar. At first glance, this might seem respectful, as it avoids stereotypes or “cheap” Orientalist decoration, but at the same time, it removes all signs of the book’s Persian origins. The design neutralizes Khayyám’s voice, fitting it into an English bookshelf as if it were always meant to be there. This matches Black’s idea that books such as this allow readers to possess the East in a comfortable, familiar form. The Persian poem becomes less Persian and more English in both appearance and meaning.

Second, the use of FitzGerald’s first translation (see figure 2) is one of the clearest examples of cultural reshaping. FitzGerald’s translation has been widely criticized for the liberties he took with Khayyám’s Persian text. He edited, rearranged, and altered meanings, emphasizing themes he found personally meaningful. For instance, he interpreted wine almost entirely in a hedonistic way while ignoring its deeper spiritual meaning (often a metaphor for divine love), and highlighted a kind of hopeful existentialism that resonated with Victorian readers. So, even though FitzGerald’s version is undeniably poetic and has a distinctive voice, it also reflects a Western tendency to reinterpret foreign texts to suit its own tastes and questions. The changes made the poem more accessible to English readers, but they also demonstrate how Persian culture needed to be adapted or modified for Western audiences to appreciate it. One could argue that it is not entirely bad because it gave visibility to Khayyám’s work (a reach), but this supports Barbara Black’s argument that gift book editions transform Eastern works into decorative objects instead of respecting their intellectual value.

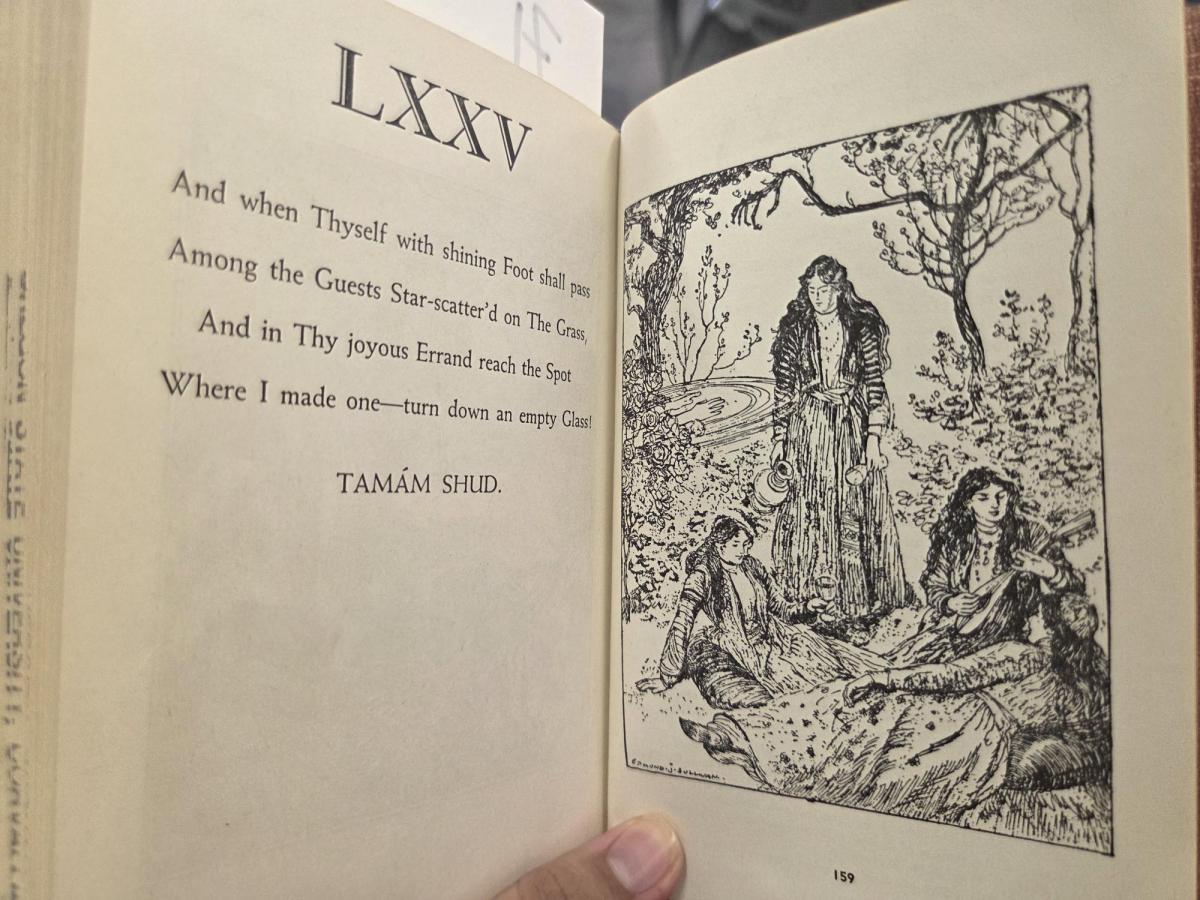

Another aspect of the edition that is worth analyzing in relation to Orientalism is the set of illustrations by Edmund J. Sullivan. Even though on the surface they may appear culturally accurate, due to the correct clothing or appearance of the people depicted, they still reinforce Orientalist ideas. One illustration that really comes to mind is the one that accompanies quatrain XLII (see figure 3). In this image, the central figure is portrayed as an alchemist or scholar, standing partially nude in scholar-like robes, with a distinctly Western-style academic cap. He is surrounded by imagery such as astrological symbols, leopards, mystical words like “Abracadabra,” and alchemical instruments. All of this reinforces Western stereotypes about Eastern knowledge as mysterious, magical, and exotic. Interestingly, the man in Western scholar’s robes appears to be teaching the other, more Eastern-looking men about this mystical alchemy. As Orientalism often works, the East is made exotic enough to fascinate but familiar enough not to challenge Western superiority.

Even with all of this in mind, the 1951 edition does not solely reduce Persian culture. There are some ways in which it shows respect, or at least curiosity, even if they are minimal. For one, Khayyám’s name is not erased; the book clearly credits him, keeping his voice (filtered, perhaps not his words, but FitzGerald’s) present and available to readers. Sullivan’s illustrations, while stylized, attempt to match the emotional and philosophical tone of the poems. And the restrained cover could be interpreted as an attempt to treat the book with dignity rather than turning it into a gaudy fantasy object. These choices suggest that the book might have been meant not just to decorate a shelf but to be read, thought about, and passed along for others to read.

In the end, this 1951 edition of the Rubáiyát shows how complicated cultural translation can be. It reflects many of the Orientalist patterns Barbara Black describes: shaping the East into something that fits Western desires, and valuing it mostly when it can be collected or reimagined. But it also shows signs of deeper engagement and even admiration. The question, then, is not whether the book is purely Orientalist or not, but how much space it leaves for Khayyám’s voice to speak for itself, even from inside a Western frame.

Sources:

Black, Barbara J. On Exhibit : Victorians and Their Museums. Charlottesville, University Press Of Virginia, 2000.

Omar Khayyám. Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. New York. Shakespear House, 1951