Ezra Pound was one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century– mainly due to his part in establishing the norms of the Imagist poetry movement; a cohort stemming from the Modernist style in the early 1900’s. Pound, being a front-runner of this particular literary movement, took it upon himself to create a “List of Don'ts” which writers could follow in order to more closely adhere to what Pound saw as being the tenets of Imagist writing. This somewhat egotistical and controlling move is in direct opposition to the free-flowing nature of Imagist writing, as well as the seemingly impulsive lifestyle Pound lived. The ever-changing and tempestuous nature of Pound’s life is reflected in the images selected for this gallery; one which follows Pound’s life chronologically, and is representative of the people and movements which he inspired, and vice versa.

Beginning with a visual representation of Pound’s early Imagist work, viewers will be able to discern the type(s) of work which the writer engaged with, and how it can be applied to multiple mediums and perceptions. Following this is an example of works by a writer by the name of Filippo Marinetti, a major proponent and trailblazer within the Futurist school of writing. Marinetti’s “Futurist Manifesto” was certainly an inspiration for Pound’s work following the same framework, and even holds ironic parallels through the Italian cultural beliefs and practices which Pound would engage with later in his life (perhaps, as some may consider, to an excessive or dangerous extent). Figure 3 demonstrates the interpersonal nature of Pound’s bohemian lifestyle in England, France, and Italy in the first third of the 20th century. Pound built very strong professional and personal relationships with many prominent American and British writers of the time, including but not limited to: James Joyce, T.S. Eliot, and Ernest Hemingway. His generous contributions to the careers of other writers enabled many of his contemporaries to publish their works with more ease than they otherwise would have enjoyed, and to see their works distributed to a much wider audience to boot (Academy of American Poets). The final image, representative of Pound’s mature life, demonstrates how his political and sociocultural leanings affected his personal and professional life.

If nothing else, Ezra Pound lived a unique life which saw him interact with some of the most influential authors of the modern era, and to hold an impact on the American writing style for the remainder of the 20th Century. By viewing the images in this gallery, readers will gain an understanding of how Pound’s life changed year by year, and how he came to be one of the most prominent figures in the modern literary canon.

Works Cited:

About Ezra Pound. Academy of American Poets, 2016.

Fig. 1 Peters, Julian. “In a Station of the Metro.” 2017. Julian Peters Comics https://julianpeterscomics.com/2017/04/04/in-a-station-of-the-metro-by-ezra-pound-1913/

Julian Peters is an artist based out of Montreal who specializes his graphic art by producing comic-based paintings. He has also produced several collections of paintings with the intention of “bringing classical poems to light” through his work. The first figure in the collection is an example of Peter’s work in transforming Imagist poetry into visual art, a painting which harkens to Ezra Pound’s 1913 work by the same name. Pound’s poem is a prime example of the imagist style: a poem which is intended to create a picture of a specific moment or scene in the mind of the reader. This brief work does just that, describing the sharp contrast of the faces in the train station against their dark and cold surroundings, making them appear as “Petals on a wet, black bough.” (Pound, 1913). Peters’ painting emulates the simplicity of Pound’s work, while also holding parallels through use of color, muted tone, and contrast. The amount of white space in Peters’ work, for example, provides viewers with a sense of the “cold” environment which Pound wanted to depict. Certainly, the bold use of black for all of the clothing and hair on the figures present provides sharp contrast; and is measured against the cherry-blossom pink utilized for the faces of the “apparitions” as Pound would refer to them. Peter’s art, in its simplicity and elegance, is as close an approximation to a visual form of what Pound’s brand of Imagist poetry was meant to demonstrate.

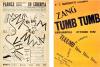

Fig. 2. Marinetti, Filippo. Left: “Après la Marne, Joffre visita le front en auto.” 1915. Right: “Zang Tumb Tumb.” 1914. Widewalls. https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/futurist-manifesto.

Pound’s use of formalized, strict, policy-esque writing in his manifesto was certainly influenced by pieces like Marx’ Communist Manifesto. Something else to consider in this same vein are the other works which might have influenced Pound in organizing statements to standardize the Imagist form of poetry. Filippo Marinetti, a poet in Italy at the turn of the 20th century, utilized Marx’ manifesto as inspiration for his own on the subject of Modernist poetry. The two images in figure 2 demonstrate Marinetti’s Futurist style: poetry with a great emphasis on sense and perception, onomatopoeia, movement, shape, and visual queues.

Similarly to Pound’s work, Marinetti’s manifesto shares the tenets of the Communist Manifesto: “... provocative discourse that calls for ideological, aesthetic and social upheaval.” (Anapur, 2016). Without works such as Marinetti’s demonstrating how art movements could utilize the power and influence of socio-political idealisms in efforts to push poetic stylings into the public view, writers like Pound might not have gained the traction and public recognition necessary to make them, and the modernist form, as integral as they were to literature in the 20th century.

Another parallel between the work of Marinetti and Pound is that both created works during war (Marinetti during WWI, and Pound during WWII). The photos included for Marinetti’s works demonstrate the visual descriptors he utilized to represent the sound of weaponry, and the diffusion of war across the entire continent of Europe between the early 1900’s and 1920. The title of his work “Zang Tumb Tumb” is actually a representation of the sound of gunfire and explosions, and demonstrates why his use of perception and the senses was so central to his Futurist style.

Fig. 3. Blake, Peter. “Ford Madox Ford, James Joyce, Ezra Pound, and John Quinn in Pound’s Paris Studio 1923.” Print, 1983. British Museum. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_2010-7089-8

This figure was included to show the interpersonal nature of writing, and how inspiration came to Pound from many different sources throughout the course of his life. At this point in his life, as a man in his mid 30’s, Pound was living a tumultuous life between England and France, and was suffering greatly professionally and personally. Luckily for him, he was surrounded by many other great writers and artists who sought his company in order to be inspired, and to share inspiration with him as well. Of these artists, namely James Joyce (pictured at Pound’s side in the attached photograph) and T.S. Eliot shared the bulk of the influence other creators had on Pound.

Eliot, Joyce, and Hemingway all looked upon Pound as being a mentor, and a figure to bounce ideas off of in terms of their writing careers. For example, Pound declared Eliot’s The Lovesong of J. Alfred Prufrock as “... the best poem I have yet had or seen from an American…”, upon reading just a draft of the poem when Eliot visited Pound in 1914. Similarly, in 1922 when Hemingway and his wife moved to Paris, they immediately struck up a friendship with Pound and his wife– leading to Hemingway asking Pound to edit some of his short works. Because of these friendships and partnerships, Pound was able to pull upon a variety of life events and relationships as inspiration for his works. He was also a master at networking in order to progress as a professional– regularly calling upon friends and acquaintances for favors to get his works published, or to meet with influential people/organizations in order to see his ideas placed into the public’s view. Without this ability, Pound would never have been able to meet with the members of the United States Congress, Benito Mussolini, and some of the most influential writers of the 20th century.

Fig. 4. “Pound Returns to Naples, Italy.” 1944. Flashbak.

Due to a life in Paris which was found to be unsuitable for Pound and his wife (as well as the fact that most of Pound’s personal and professional relationships were deteriorating at this point in his life), the Pounds moved to Italy in 1924. While in Italy, Ezra continued to demonstrate public support for antisemitic beliefs and practices, while also showing genuine interest in Mussolini’s fascist blend of leadership and policy. Pound met with Mussolini in January of 1933, and presented him with a draft of The Cantos, which was Pound’s epic poem rooted in Italian political, and social constructs. Pound utilized his verbal and written eloquence at this point in his life to demonstrate support for Mussolini and Italian fascism by creating propaganda for his cause. Pound wrote letters to American and British politicians in the 1930’s and 40’s expressing antisemitic views as well as admonishment for the political policies of Roosevelt during the WWII era. Pound also wrote transcripts for, and himself completed radio broadcasts in support of Mussolini’s ideals, and the German occupation of Italy. Pound did so through the “Ente Italiano per le Audizione Radiofoniche”, as well as a radio station sponsoring the Salo Republic: an unofficially recognized puppet-state of Northern Italy which was under German control during the occupation. The photo here is a simple snapshot of Pound showing a fascist salute upon arriving in Naples, Italy. I wanted to include this photograph as a representation for this chapter in Pound’s life, as well as a representation of the connections between his beliefs toward his art form, as well as his beliefs surrounding social and cultural issues during the time period. I suppose there is some irony between Pound’s creation of an Imagist “manifesto”, and his political leanings during the mid-20th century; the bottom line is that this time of Pound’s life was a tumultuous and intriguing period which certainly influenced how he and his works were publicly perceived.