George Du Maurier made his reputation as a "Sixties" illustrator. The term "Sixties" refers to an important school in the history of British book illustration that technically spans 1855–1875, but takes its name from the decade when much excellent work in the realistic school of illustration reigned supreme. During this period, many trained artists entered the lucrative field of book illustration. Sir John Everett Millais is considered the foremost "Sixties" illustrator, but Du Maurier along with others including William Holman Hunt, Frederick Walker, and Luke Fildes made their mark as "Sixties" artists.

Du Maurier began his artistic career as a painter, but he left painting altogether to become a book illustrator when, in 1860, he lost vision in his left eye; believing his compromised vision prohibited a career in easel painting and fearing total blindness, Du Maurier made a decision to become an illustrator. A fan of the caricaturists, Du Maurier was an inheritor of two illustrative traditions: realism and caricature. He illustrated novels by Elizabeth Gaskell, Thomas Hardy, and William Thackeray. He also was a staff cartoonist or Punch, the leading Victorian humor magazine. In the 1890s, Du Maurier published three author-illustrated novels for an adult readership marketed by a US publisher; they became enormously popular in England and America. In his books and cartoons, he is known for drawing statuesque women. His illustrations favor figures over backgrounds and close-ups over panoramas. He distinguishes himself as an illustrator For his range as an artist, his mastery of caricature and realism, and his ability to convey drama as well as humor. And his author-illustrated fiction became so popular that it sparked stage and film productions from the late nineteenth through the mid twentieth centuries. Du Maurier's best known character, Svengali, has a life today outside of his novel.

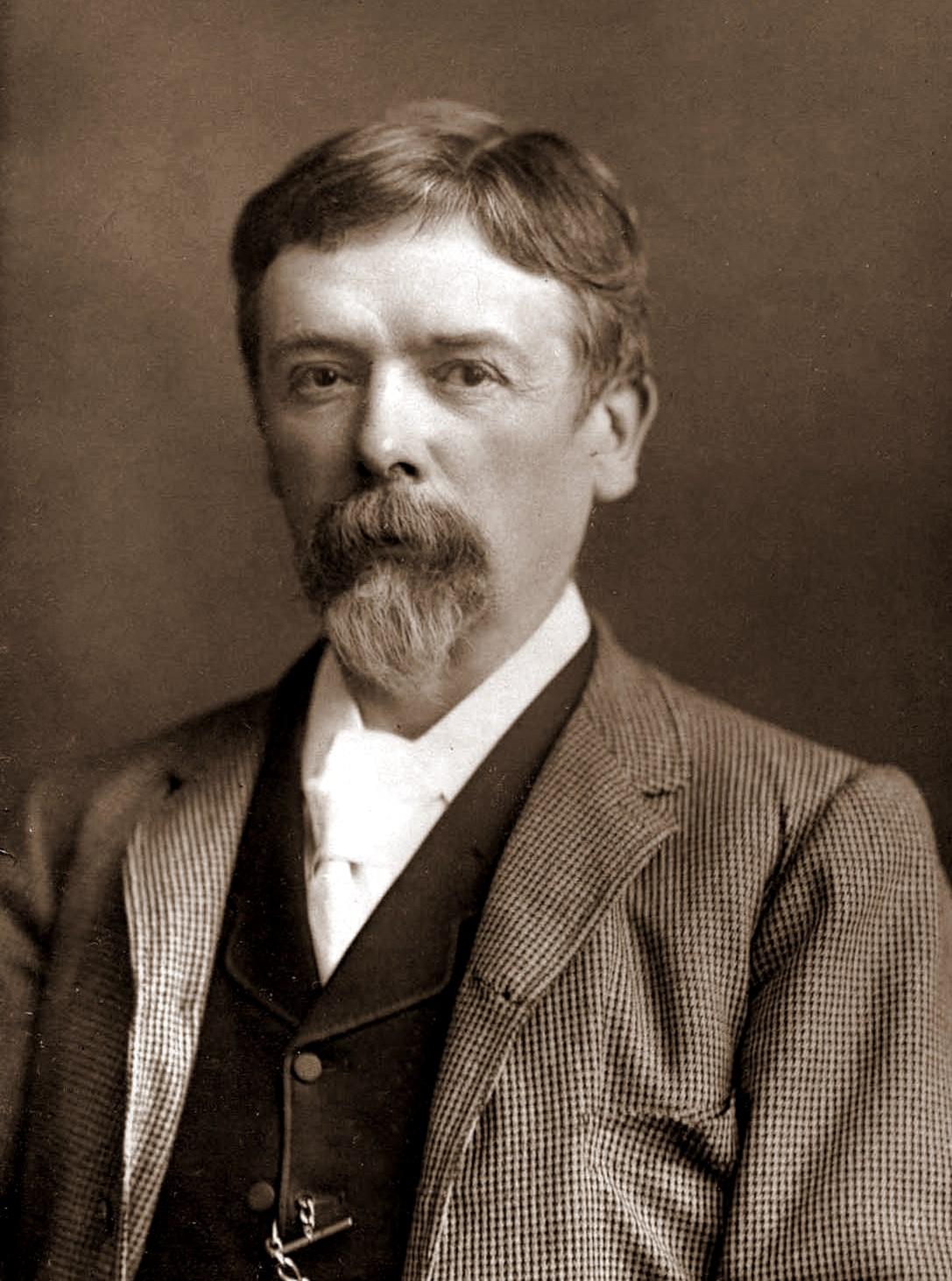

Pictorial Press, Photographic portrait of George Louis Palmella Busson du Maurier, ca. 1896, Wikipedia. This photograph by the Pictorial Press was taken shortly before Du Maurier's death. George Louis Palmella Busson du Maurier (1834-96) was born in Paris. The family settled permanently in England when George was seventeen. He distinguished himself as an artist, illustrator, cartoonist, and author. He is father of the British stage actor Sir Gerald Du Maurier and grandfather of the well-known novelist Daphne Du Maurier of Rebecca (1838) fame.

Three Novels Written and Illustrated by George Du Maurier, from the personal collection of Catherine J. Golden. In the 1890s, Du Maurier published three autobiographical author-illustrated novels that became Victorian blockbusters and entertain psychological phenomenon. Peter Ibbetson (1891) begins with a thinly veiled rendition of the author-illustrator's own Parisian boyhood. In England, the hero, Peter, finds himself imprisoned for a crime of rage against his cruel uncle but finds a way to be with his lover, Mary Towers, through telepathic dreaming, called "dreaming true." His best-known Trilby (1894) tells about three English painters in Paris who fall in love with a laundress turned model, Trilby, who is hypnotized by the menacing musical genius, Svengali. The Martian (1898), the least successful novel of the three, follows artist Barty Josselin who attempts to be an artist, loses his vision, and becomes suicidal. Visited in his dreams by his guardian spirit Martia, a female spirit from Mars, he writes successful novels through the process of "automatic writing"--Martia communicates his stories and writes through him, leading to his successful career as an author.

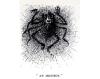

George Du Maurier, "An Incubus," for Trilby, 1894, scanned image by Philip Allingham, The Victorian Web. Trilby, written and illustrated by Du Maurier and published serially in Harper's, quickly became a bestseller and is credited for impacting the publishing of “sellers” (as publishers called bestsellers then). It tells about a menacing Jewish musical genius named Svengali, who hypnotizes Trilby O’Ferrall, a French-Irish laundress and an artist’s model, who, under Svengali’s control, becomes an opera virtuoso. Trilby boosted sales of Harper’s and sold close to 300,000 copies during the first year of its publication (Kelly, George Du Maurier 87). To Trilby, Du Maurier brings theatricality in illustration and a persistent racialized depiction of the Jew from the caricature tradition to his self-illustrated fiction. “An Incubus” is the most darkly comic of the Svengali illustrations. The title comes from a quote where Trilby sats Svengali is “a dread, powerful demon, who . . . oppressed and weighed on her like an incu bus” (136–37). In this small but powerful vignette, Du Maurier draws Svengali as part human, part insect, and part demon. He has spidery legs, “killer” eyes, a pronounced nose, and thick wild hair, here fashioned to suggest a Jew’s devil’s horns. Biographer Richard Kelly calls this a nightmare cartoon: Du Maurier is “working within the nineteenth-century visual tradition epitomized in the drawings of Cruikshank,” a leading caricaturist.

George Du Maurier, "'Et maintenant dors, ma mignonne!'" for Trilby, 1894, scanned image by Philip Allingham, The Victorian Web. Svengali’s hypnotic powers emerge to theatrical effect in this full-page engraving. Svengali here is mesmerizing tone-deaf Trilby, who--under Svengali's control--becomes a virtuoso who performs in all the great European cities, but wakes with no memory of her success as a singer. This illustration includes three figures—Marta, Svengali’s aunt, who looks after Trilby and here places the diva’s crown on her head; Trilby herself, dressed up as the opera diva called La Svengali; and Svengali, kneeling before Trilby, inducing a trance. Du Maurier grants Trilby a regal beauty and sensuality that entrances the three English painters as well as Svengali.

George Du Maurier, "Taking One Too Much at One's Word." From English Society. Sketched by George Du Maurier, 1897, scanned by George Landow, The Victorian Web. Du Maurier earned a reputation for his sketches of Victorian society that filled the pages of Punch and English Society. Many of his most famous plates that satirize the pretentions of the rising middle class, as is the case with "Taking One Too Much at One's Word." The dialogue that accompanies this image reads: Hostess: — “Won't you play us something, Mr. Spinks?”/ Spinks, a Musical Amateur who thinks a good deal of himself, in spite of his modesty: — “Oh, don't ask me – you are all such first-rate performers here – and you play such good music, too.”/ Hostess: — “Well, but we like a little variety, you know.” The key word in this dialogue is "variety," which means variety entertainment , common in the Victorian era, and could include magic shows, ventriloquism, juggling, and comedy sketches. Is this a dig at Spinks, suggesting that those who think they play better than they do transform an evening of music into a variety show? Here, too, as in the Trilby illustrations, Du Maurier draws statuesque women who command the Victorian drawing room.

Theatrical Release Poster, Peter Ibbetson, 1935, Directed by Henry Hathaway, Starring Gary Cooper and Ann Harding, Wikipedia. Both Peter Ibbetson and Trilby were adapted for the stage and made into films. The 1935 film version with Gary Cooper in the title role of Peter Ibbetson was well received. But Du Maurier’s Trilby created a consumer phenomenon called Trilby-mania. Galleries displayed prints from the book. Real and fictitious claims about the novel filled British and American newspapers. A narrow-brimmed hat worn in the London production of the play came to be known as a "trilby." The character of Trilby, akin to Sherlock Holmes, came to be thought of as a person, not a book character, and had a city in Pasco County, Florida named after her that still exists today. The name Svengali is still synonymous with a manipulator, even to those who have never read the novel.