Julia Margaret Cameron’s work moved away from conventional photography of the 1850s and 1860s. She believed that the photographs of the time were uninspired and undeserving of the status and prestige of distinguished art (Wolf). When Cameron decided to partake in photography as a career, she was committed to standing out from the ordinary photographs of the time. Cameron wanted to deviate from the “normal”, an action that would seem difficult for anyone, especially women, who wanted to challenge the customs of Victorian society in England. The mere fact that she was a talented woman photographer immediately put her under scrutiny. Her art, therefore, was under the constant risk of unrelenting criticism. Cameron’s defiant portraits, however, amassed great publicity in England and beyond. Her photographs were displayed in London and Paris. She was awarded several honors for her work, and her photos sold out as soon as they were made during the prime time of her career (Kennedy et al.). Some of her photographs were even purchased by Queen Victoria and the Crown Princess of Prussia (Wolf).

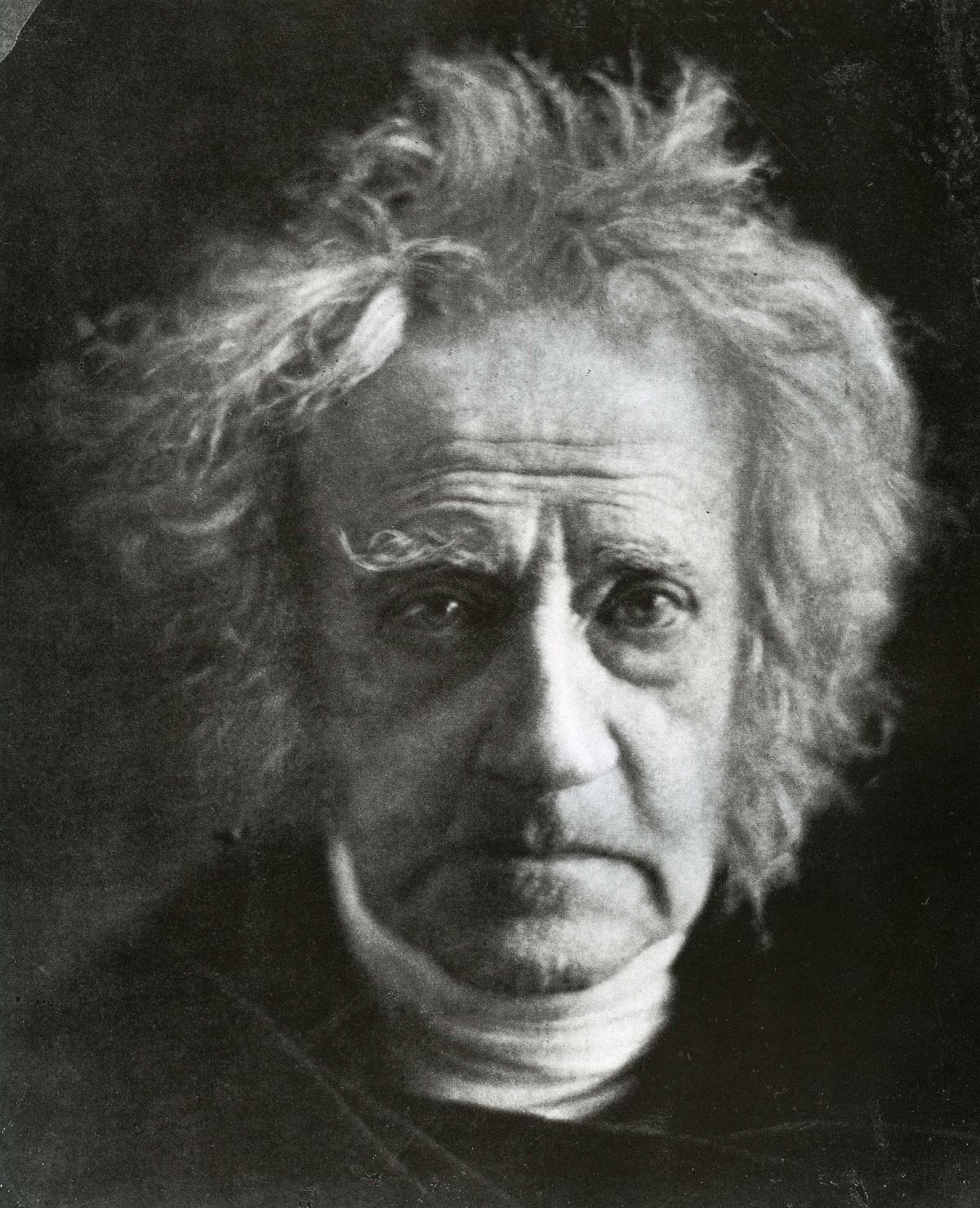

Cameron herself was humble regarding her fame and achievements. In a letter by Cameron from 1867, Cameron wrote to an unidentified recipient about her achievements and included praise of her work by several respected figures. “These praises I record not from vanity but because I am not popular - because only the artistic eye yet trusts itself boldly to praise my Photographs” (Cameron). Cameron was hoping to convince the recipient of coming into her studio and receiving a portrait of him/herself. Despite her humility, the praise that Cameron mentioned in her letter was an indicator of the public’s reception of her work. Sir John Herschel, a renowned astronaut and chemist, was regarded by Cameron as her mentor. “He thinks,” Cameron wrote about Sir Herschel, “my photographs surpass all that he has ever seen done or thought could be done in photography” (Cameron). Margaret also includes the poet Gabriel Rossetti and the painter George Watt’s praise about her portrait of a gentleman called Thomas Carlyle. It is apparent that those with an “artistic eye” were bewildered by the way Cameron put spirit into those she took the photographs of. Her art hauled people into her studio, hoping to be immortalized by Cameron’s simplistic, yet moving, photographs (Wolf).

Julia Margaret Cameron, Sir John Herschel, 350 x 277 mm, albumen print from a collodion glass plate negative, 1867. The Wilson Centre for Photography, London.

Despite her success, Julia Margaret Cameron did not make enough from her art to be able to financially support her stay in England. Cameron and her husband faced financial problems after their move into England and were forced to settle for life in Ceylon for a more economical life (Green-Lewis). Cameron’s move out of England does not take away from her achievements and popularity. She so passionate about her work that she did not accept random clients. She also regularly gave out expensive albums as gifts (Green-Lewis). It is also important to note that the Camerons were already facing financial difficulties when she decided to enter the field of photography (. These factors, combined with the expenses of her five children, made it increasingly difficult for the Camerons to maintain their upper-middle class style of life and contributed to the financial hardships that she and her husband faced (Green-Lewis). After her move to Ceylon, Cameron continued her photography career, taking pictures of the people of Kalutara, the village she lived in. Her work, however, never reached the heights that it reached in England.

Julia Margaret Cameron, Cingalese Girl, 1875. Albumen print, 35.1 x 18.7 cm, Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum, 86.XM. 636.

Even though Cameron’s work was met with positive response from notably well-known people, some photographers from the Photographic Society of London expressed belittlement and disdain towards her style. To the criticism, Cameron said “The Photographic Society of London in their Journal would have dispirited me very much had I not valued that criticism at its worth. It was unspairing and too manifestly unjust for me to attend to” (Wolf). Cameron was able to overcome the barrier of traditional roles in the Victorian era due to her unconventional, profound portraits the emphasized people’s natural facial structure with no emphasis on the background of the pictures or any props. Her photographs emphasized simplicity of composition against the cruelty of nature and no reference to a popular theme or style (Wolf).

References:

Green-Lewis, Jennifer. "From Life: The Story Of Julia Margaret Cameron And Victorian Photography (Review)". Biography, vol 27, no. 3, 2004, pp. 613-617. Project Muse, doi:10.1353/bio.2004.0065.

Kennedy, Nora W. et al. "A Hidden Photograph By Julia Margaret Cameron". Metropolitan Museum Journal, vol 53, 2018, pp. 162-171. University Of Chicago Press, doi:10.1086/701748.

Wolf, Sylvia. Julia Margaret Cameron's Women. Art Institute Of Chicago, 1998.