In Charles Dickens's The Cricket on the Hearth (1845), toys allow Blind Bertha to interface with her physical and social environment.

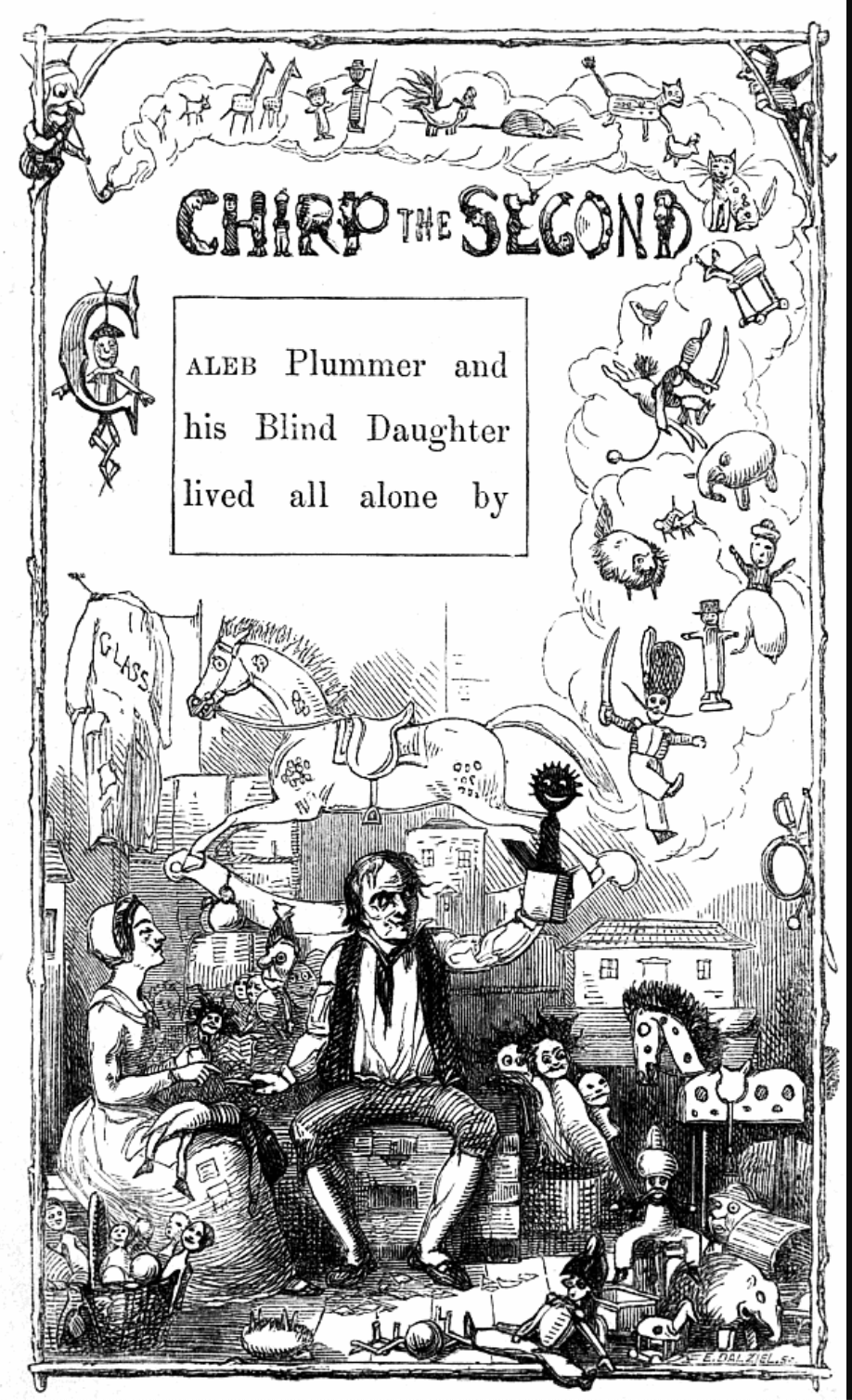

Caleb Plummer and his blind daughter Bertha build toys for toy merchant Gruff and Tackleton. Though their home is "a little cracked nutshell of a wooden house" (188), Bertha "never knew that ugly shapes of delf and earthenware were on the board; that sorrow and faint-heartedness were in the house" (189). Caleb, inspired by the Cricket Spirit of his home, turns Bertha's "great deprivation... into a blessing" by lying about their poverty. Despite Bertha's blindness, she works alongside her father, in a working room filled with houses, "finished and unfinished, for Dolls of all stations in life" (189-190).

With "suburban tenements of Dolls of moderate means; kitchens and single apartments for Dolls of the lower classes; capital town residences for Dolls of high estate," (190), Caleb and Bertha's dolls and toys represent the Two Nations of nineteenth-century England. Just as Caleb embellishes and improves Bertha's conception of her living conditions and social status, Caleb and Bertha, as "the makers of these Dolls had far improved on Nature" ( ), by dressing dolls of "the nobility and gentry" in satin, and building Doll-ladies of distinction with "wax limbs of perfect symmetry" (190). Caleb and Bertha's dolls in a lower social scale are "made of leather; and next of coarse linen stuff," (190), while dolls for "common people...had just so many matches out of tinder-boxes for their arms and legs, and there they were -- established in their sphere at once, beyond the possibility of getting out" (190). Dickens's detailed description of the differences in the Plummer dolls, as related to the social status each doll is meant to represent, illustrates the role of toys as a proxy for the social, political, and environmental conditions in the real world.

When Bertha asks her father to describe her beloved Tackleton's fiancé May, Caleb uses their dolls to help conjure Bertha's mental imagery, stating "[her shape --] there's not a Doll's in all the room equal to it!" (196). In this way, the dolls and toys function as tool for understanding and imagining the real world that Bertha is presumed to have limited access to, given her blindness.

Considered from the perspective of Disability Studies, Bertha's productivity as a doll-maker offers a counter to nineteenth-century notions of blindness as a marker of sloth, though her connection to toys links her to James Gall's assertion of a blind person's "state of continuous childhood" (Caeton 35).

Sources:

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol and Other Christmas Books. Edited by Robert Douglas-Fairhurts, Oxford University Press, 2006.

Dickens, Charles. The Cricket on the Hearth: A Fairy Tale of Home. Illustrated by Richard Doyle, Project Gutenberg, 1845.