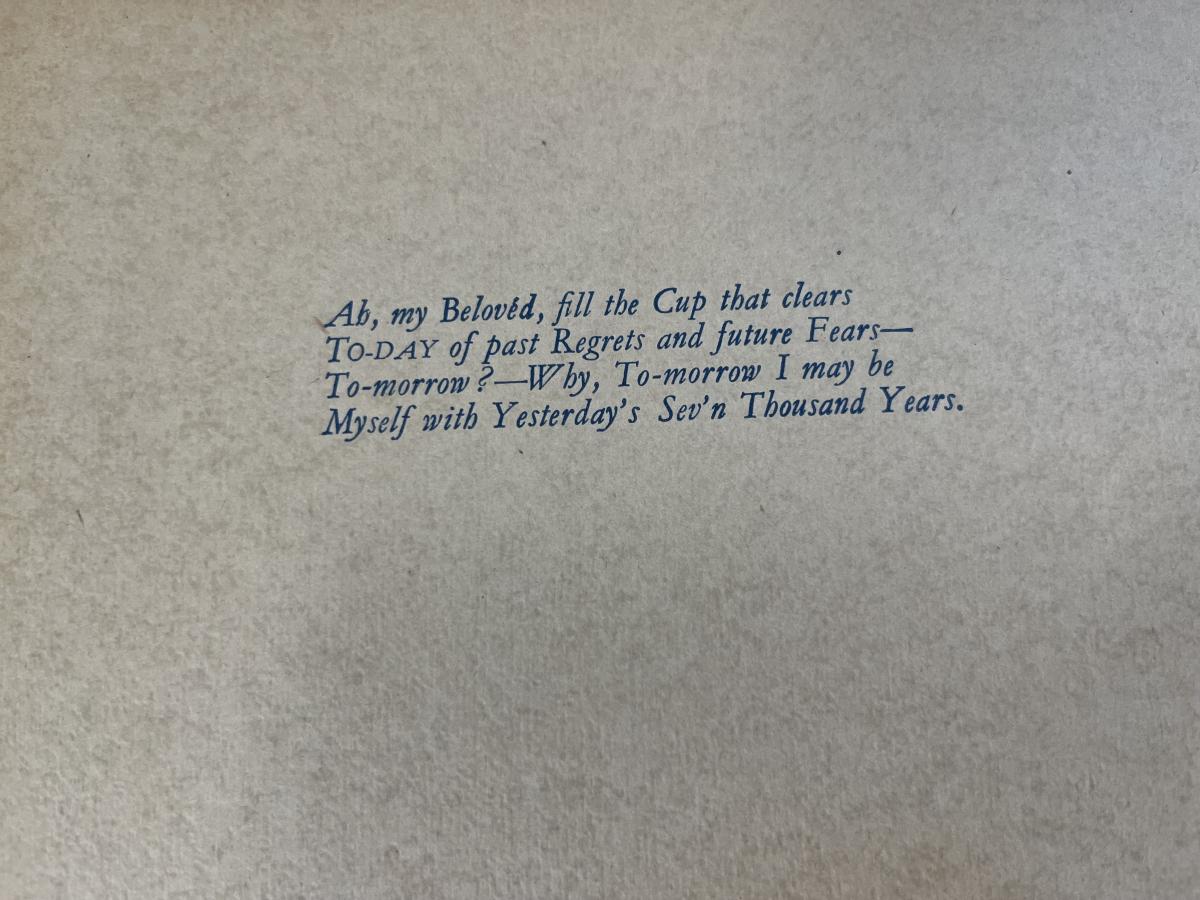

After quatrain XXIV there is a break in the format of the poem to include an illustration and bring back a previous quatrain, XX. The illustration and the quatrain at first glance appear to be the same, and the illustration is noticeably a literal depiction of the quatrain. But the illustration and the quatrain do not fully go together as they first appear; the illustration brings out the falseness that the quatrain/poem claims about how one should live their life in pleasure and the moment.

The center of the illustration is the man (assumed speaker of the poem), speaking with his Belovèd who has brought him a jar to fill his cup. She looks upon him with tenderness and his facial features show distress, that something is weighing down on his heart/mind. This is a literal depiction of the first two verses in quatrain XX, “Belovèd, fill the Cup that clears/TO-DAY of pasts Regrets and future Fears”. Here she comes with that drink, wine, to fill his cup to help ease his worries and fears. In the quatrain there is a break, with the horizontal line “—” where it gives the rhythm of a conversation, the Belovèd has spoken here, “—/To-morrow? —Why, To-morrow I may be/Myself with Yesterday’s Sev’n Thousand Years” (verses 2-4). In these verses the speaker shoves off the concerns or worries that tomorrow might bring, as if his Belovèd said something regarding the next day, because tomorrow he may just become something of the past, never going on further. Therefore, all in all, we should enjoy the present moment, and forget the future/past in the current pleasure. Even the illustration itself points to being focused in the present moment because only the current interaction between the speaker and Belovèd has detail in the illustration, everything beyond them does not have detail besides a basic outline, you cannot make out fully what is yonder. Appearing as a direct depiction of the quatrain at first glance but looking closer you begin to see how it largely differs from the quatrain. Not every piece of information is given in the poem, leading the artist, Robinson, to make certain choices when creating this illustration. He bases it on what would be the norm in society at the time. For instance, not once in the whole poem does it specify who the Belovèd is. The speaker could be referring to a friend, a sibling, or either a man or a woman. Even further, in Persian poetic tradition other than being another person, the Belovèd could be the self or God. But Robinson chooses to depict the Belovèd as a woman because it would be socially appropriate for the Belovèd to be a woman rather than a man. Not only that, but the speaker and other men in the other illustrations appear to look somewhat like they are from Persia, stereotypical attributes given in Western art, their skin tone is darker, and they appear in what looks similar to clothing that men would wear, and they have their facial hair grown out. But here we see a woman who looks just like a standardized Western white woman appearing as this Belovèd. This would not be a believable depiction of a realistic interaction.

Seeing how the picture tries to grasp the view of life that the poem conveys, yet fails to accurately depict it, sheds light on the falseness of this view of life. It is unattainable and selfish. For instance, the Belovèd is only seen as a helper to the speaker, giving him the drink and pleasure he so desires, she is not even given a full body and has little space in the illustration. Whereas the speaker is clothed in colors that represent high-ranking societal status in Persia (Joe), blue and red, and his whole body is seen, he is the center of attention in the illustration with the bright colors and flowers bordering him, calling the viewer to look at him. This way of life that the poem encourages is one of a selfish life to only focus on the pleasure of oneself and forget the past. One cannot create meaningful relationships, without a wall blocking them from being intimate, physically/emotionally/spiritually, with someone else.

References:

Khayyám, Omar. Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. Translated by Edward FitzGerald. Illustrated by Charles Robinson. Collin’ Clear Type Press, 1929.

Joe, Jimmy. “Ancient Persian Clothing: The Irresistible Fashion of Ancient Attire.” Timeless Myths, 11 Apr. 2022, www.timelessmyths.com/history/ancient-persian-clothing/.