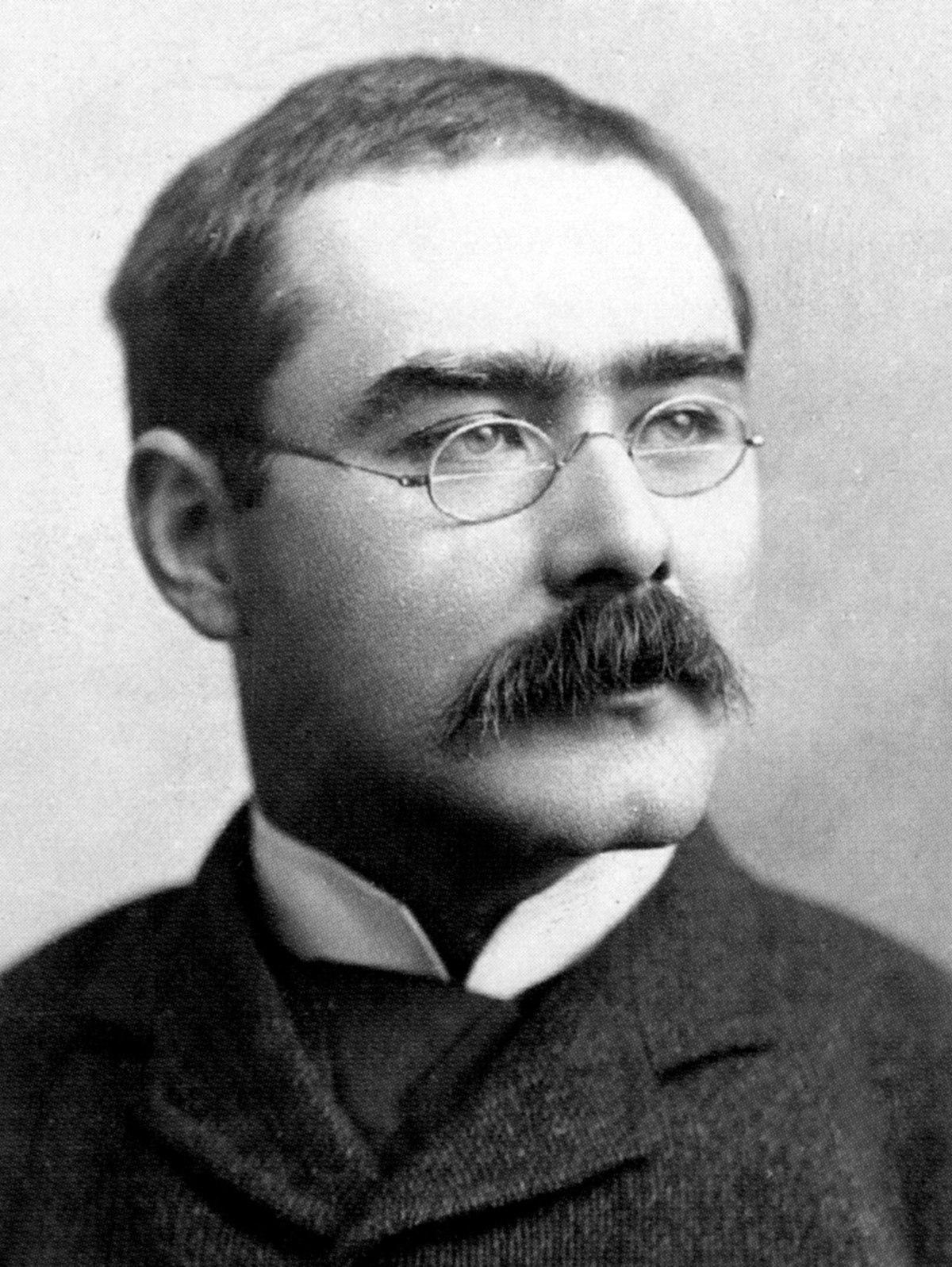

Rudyard Kipling, whose full name at birth was actually Joseph Rudyard Kipling, was born on December 30, 1865 in Bombay, India to Alice Macdonald Kipling and John Lockwood Kipling. When he was six years old, he and his sister were left in a foster home in England where he was bullied and abused. Years later, he faced bullying again while at college but he acquired a love for literature that became his creative outlet. After college, he returned to India where he worked as a journalist and editor, writing about India and Anglo-Indian society. He published his first work, a volume of poetry entitled Departmental Ditties, in 1886 and six volumes of short stories within the next few years. His work received critical acclaim, and he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1907.

Since Kipling was born in India, he faced cultural identity issues and bullying, which had a profound influence upon his work. Assuming animal forms at times, some of his characters are similarly torn between cultures and social communities or face various moral dilemmas and conflicts. For instance, Mowgli from The Jungle Book is raised by wolves in the jungle, but he is an outsider who is not like the others who truly belong in the wild. The jungle becomes a dangerous place for him, but he struggles to remain a part of the only home he knows. Overcome with his identity crisis and longing to belong, he leaves the jungle for the village. Mowgli begins adapting only to find that he does not quite fit within that environment either. He abandons the village and returns to the jungle. Kipling’s darker side in The Jungle Book yields to lighter work for younger audiences. His Just So Stories offers whimsical and imaginative tales for children that delight them with fanciful explanations as to how and why animals look and behave the way they do, all while imparting valuable lessons. Using humor and nonsense words, Kipling entertains and nourishes inquisitive young minds.

Portrait of Rudyard Kipling, 1895, republished in 1907, from Rudyard Kipling, written by John Palmer. This first plate shows a portrait of Rudyard Kipling taken on June 15, 1895 by Elliott and Fry (a Victorian photographic studio) when Kipling was nearly thirty years old. In addition to his writing prowess, he had a flair for art much like his father, John Lockwood Kipling, a successful artist who drew illustrations for The Jungle Book. Two of his uncles, Sir Edward Burne-Jones and Sir Edward Poynter, were esteemed Victorian painters. Kipling was the author-illustrator of the famous children’s classic, Just So Stories. As with some of the greatest children's literature, Just So Stories was inspired by a real child. In this case, Kipling's daughter Josephine (nicknamed Effie) served as his inspiration. He created silly stories so that she would learn important virtues such as honesty, integrity, decency, and humility. Though well-accomplished, Kipling himself was modest and turned down many prestigious awards, including opportunities at knighthood. He believed that people should work hard to achieve their goals, take responsibility for their actions and failures, and never live in the past. His work embodies the adversities from his past along with his ethical principles, resulting in dark and light themes within his writing.

W.H. Drake, "When the Moon Rose over the Plain the Villagers Saw Mowgli Trotting across, with Two Wolves at his Heels," 1895, from Rudyard Kipling's The Two Jungle Books, Wikimedia Commons, scanned by Nichole Deyo. This second plate depicts Mowgli, the main human character within Rudyard Kipling’s popular The Jungle Book. Mowgli struggles with an identity crisis as he does not fully belong in the jungle, nor does he fully belong in the village amongst humans. As he walks back to the jungle with the wolves, he accepts his hybrid state—part wolf, part man. Kipling’s background as an Anglo-Indian undoubtedly had a heavy impact upon shaping Mowgli’s character. His duality of cultures and displaced sense of belonging is easily recognized within the lamenting young Indian, boy who, through no fault of his own, can never truly fit in.

R.H. Disney, "The Jungle Book (Disney The Jungle Book) (Little Golden Book)," 2003, from AbeBooks. This third plate depicts the book cover for Disney’s version of The Jungle Book. With children as the intended audience, this version is a critical disconnect since the storyline undergoes a vast transformation. Mowgli’s identity crisis within Kipling’s version is extremely minimized. The cartoonish smiling bear reveals how Disney’s light-hearted makeover replaces Kipling’s darker storyline. There are stark contrasts between the two versions as Disney exercises its creative license to add additional playful characters and eliminate the sinister elements. With rich, verdant foliage and pretty flowers, Disney’s jungle is a pleasant place vis-à-vis the treacherous landscape Kipling writes about, where his Mowgli character must not only worry about the many dangers but also struggle to fit in. Eventually, he reluctantly leaves the wilderness to live amongst humans when he realizes that the jungle is not fit for human habitation. In contrast, Mowgli from Disney's version hesitates to leave the jungle but enthusiastically chooses to be with Shanti, a human girl who captures his heart.

Rudyard Kipling, “The Elephant's Child Having his Nose Pulled,” 1926, from his Just So Stories, The Victorian Web, scanned by George P. Landow. This fourth plate depicts the perils of insatiable curiosity which can not only harm cats, but young elephants as well! The cunning crocodile is submerged beneath the water with just its head and snout above the surface so that it can grab hold of the elephant child’s “nose.” As the elephant struggles to free himself, his nose stretches, transforming into an elongated trunk. Though sore and unsightly, the elephant’s new trunk proves useful, and he inspires other elephants to undergo facial reconstruction. This is why “all the Elephants you will ever see, besides all those that you won’t, have trunks precisely like the trunk of the ‘satiable Elephant’s Child.” Within a smaller image below the scene from the story, Kipling includes a display of animals in pairs walking into an ark. Kipling uses images of the biblical Noah’s Ark to honor his daughter Josephine since one of her favorite toys was her Noah’s Ark play set.

Rudyard Kipling, "The Whale Swallowing the Mariner," 1926, from his Just So Stories, The Victorian Web, scanned by George P. Landow. This fifth plate shows a ravenous whale swallowing a marooned mariner. Outsmarted by the sole remaining fish in the sea, the whale thinks he can eat a man but this clever mariner creates a ruckus from within, annoying the whale with hiccoughs. Using his wisdom and a jack-knife, the man cuts his raft into a grating, which he wedges into the whale’s throat before escaping. “By means of a grating I have stopped your ating,” he tells the whale, who can no longer eat anything but tiny fish. Kipling delightfully engages readers by interjecting witty advice within parentheticals to emphasize the “important” details, such as the mariner’s suspenders which are later used to tie pieces of the raft together to create the grating. His descriptive words evoke enchanting imagery, such as when he describes how the man finds himself "inside the Whale's warm, dark, inside cup-boards." Other rhyming and nonsense words such as “ating” flow in a lyrical manner.

Rudyard Kipling, "The Whale Looking for the little 'Stute Fish," 1926, from his Just So Stories, The Victorian Web, scanned by George P. Landow. This sixth plate depicts the frighted little ‘stute fish hiding from the angry whale he deceives in an attempt to save his life. Being the last fish in the ocean, the ‘stute fish named Pingle is responsible for the whale eating a man instead. The man outsmarts the whale and now the whale is hunting for the devious small fish hidden beneath the door-sills of the equator. Fortunately, the whale’s temper abates, and he and the little fish become good friends. Kipling’s brilliant imagination and flair for whimsy add greater depth to his illustration with the inclusion of two giants, Moar and Koar, who protect the equator. The doors (which must always be kept shut) thrill curious minds with wonder and marvel and beg the question: What if they were opened?

Rudyard Kipling, "The Dijinn in charge of All Deserts," 1926, from his Just So Stories, The Victorian Web, scanned by George P. Landow. This seventh plate shows an angry djinn confronting a wicked, lazy camel who refuses to do his share of work at the beginning of the world. Each time the other animals ask for his help, he lets out an arrogant "humph!" Frustrated by the camel's idleness, the magical djinn teaches him a lesson by burdening him with a “humph” (now called “hump”) on his back, which allows him to work for days without eating or drinking so that he can catch up on his work. The illustration is comprised of two images, one that focuses on the djinn with the camel and a smaller one underneath that provides a panoramic view of the dessert when it is “so-new-and-all.” Somewhere in that vast dessert, amidst the volcanoes, mountains, a lake, and even Noah’s Ark (because we know it’s one of Josephine’s favorite toys!), there is a vengeful djinn chastising a petulant camel.

Bibliography:

Disney, RH. "The Jungle Book (Disney The Jungle Book)." | AbeBooks, Golden/Disney, 1 Jan. 1970, www.abebooks.com/servlet/BookDetailsPL?bi=31822408382&searchurl=ds%3D20%26kn%3DJungle%2Bbook%2Bdisney%26sortby%3D17&cm_sp=snippet-_-srp1-_-image5.

Kipling, Rudyard. Just So Stories for Little Children. Illustrated by the Author. London: Macmillan, 1926.

The Victorian Web. < http://www.victorianweb.org/ >. Web. 08 April 2024.