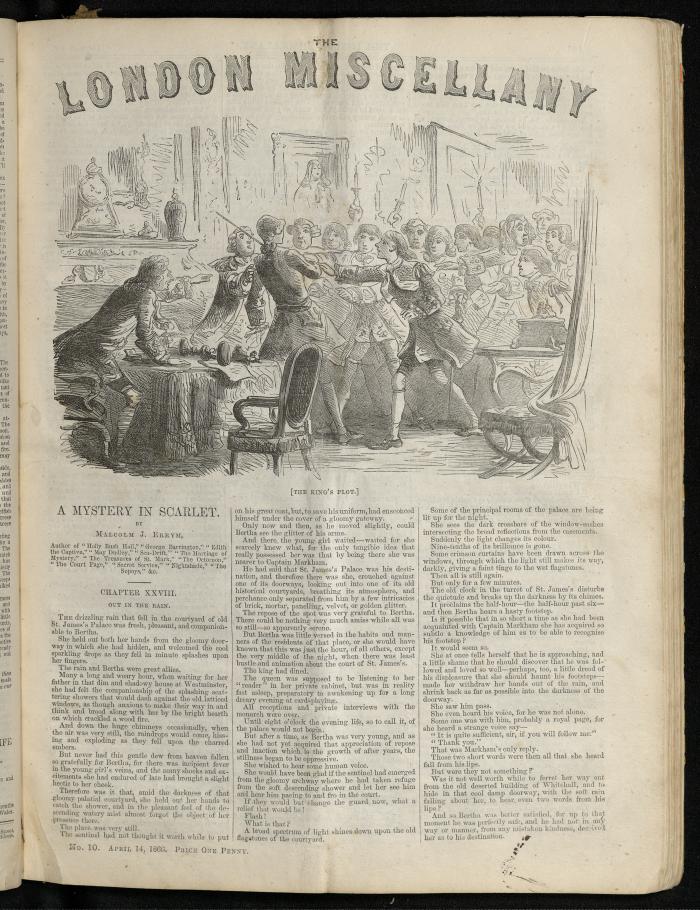

A MYSTERY IN SCARLET.

by

Malcolm J. Errym,

Author of "Holly Bush Hall," "George Barrington," "Edith the Captive," "May Dudley," “Sea-Drift," "The Marriage of Mystery," "The Treasures of St. Mark," "The Octoroon," "The Court Page," "Secret Service," "Nightshade," "The Sepoys," &c.

CHAPTER XXVIII.

OUT IN THE RAIN.

The drizzling rain that fell in the courtyard of old St. James's Palace was fresh, pleasant, and companionable to Bertha.

She held out both her hands from the gloomy door way in which she had hidden, and welcomed the cool sparkling drops as they fell in minute splashes upon her fingers.

The rain and Bertha were great allies.

Many a long and weary hour, when waiting for her father in that dim and shadowy house at Westminster, she had felt the companionship of the splashing scattering showers that would dash against the old latticed windows, as though anxious to make their way in and think and brood along with her by the bright hearth on which crackled a wood fire.

And down the huge chimneys occasionally, when the air was very still, the raindrops would come, hissing and exploding as they fell upon the charred embers.

But never had this gentle dew from heaven fallen so gratefully for Bertha, for there was incipient fever in the young girl's veins, and the many shocks and excitements she had endured of late had brought a slight hectic to her cheek.

Therefore was it that, amid the darkness of that gloomy palatial courtyard, she held out her hands to catch the shower, and in the pleasant feel of the descending watery mist almost forgot the object of her presence there.

The place was very still.

The sentinel had not thought it worth while to put on his great coat, but, to save his uniform, had ensconced himself under the cover of a gloomy gateway.

Only now and then, аs he moved slightly, could Bertha see the glitter of his arms.

And there the young girl waited —waited for she scarcely knew what, for the only tangible idea that really possessed her was that by being there she was nearer to Captain Markham.

He had said that St. James's Palace was his destination, and therefore there was she, crouched against one of its doorways, looking out into one of its old historical courtyards, breathing its atmosphere, and perchance only separated from him by a few intricacies of brick, mortar, panelling, velvet, or golden glitter.

The repose of the spot was very grateful to Bertha.

There could be nothing very much amiss while all was so still—so apparently serene.

But Bertha was little versed in the habits and manners of the residents of that place, or she would have known that this was just the hour, of all others, except the very middle of the night, when there was least bustle and animation about the court of St. James's.

The king had dined.

The queen was supposed to be listening to her "reader" in her private cabinet, but was in reality fast asleep, preparatory to awakening up for a long dreary evening at card-playing.

All receptions and private interviews with the monarch were over.

Until eight o'clock the evening life, so to call it, of the palace would not begin.

But after a time, as Bertha was very young, and as she had not yet acquired that appreciation of repose and inaction which is the growth of after years, the stillness began to be oppressive.

She wished to hear some human voice.

She would have been glad if the sentinel had emerged from the gloomy archway where he had taken refuge from the soft descending shower and let her see him and hear him pacing to and fro in the court.

If they would but change the guard now, what а relief that would be!

Flash!

What is that?

A broad spectrum of light shines down upon the old flag-stones of the courtyard.

Some of the principal rooms of the palace are being lit up for the night.

She sees the dark crossbars of the window-sashes intersecting the broad reflections from the casements.

Suddenly the light changes its colour.

Nine-tenths of its brilliance is gone.

Some crimson curtains have been drawn across the windows, through which the light still makes its way, darkly, giving a faint tinge to the wet flagstones.

Then all is still again.

But only for a few minutes.

The old clock in the turret of St. James's disturbs the quietude and breaks up the darkness by its chimes.

It proclaims the half-hour—the half-hour past six—and then Bertha hears a hasty footstep.

Is it possible that in so short a time as she had been acquainted with Captain Markham she has acquired so subtle a knowledge of him as to be able to recognise his footstep?

It would seem so.

She at once tells herself that he is approaching, and a little shame that he should discover that he was followed and loved so well—perhaps, too, a little dread of his displeasure that she should haunt his footsteps—made her withdraw her hands out of the rain, and shrink back as far as possible into the darkness of the doorway.

She saw him pass.

She even heard his voice, for he was not alone.

Some one was with him, probably a royal page, for she heard a strange voice say—

"It is quite sufficient, sir, if you will follow me."

"Thank you."

That was Markham's only reply.

Those two short words were then all that she heard fall from his lips.

But were they not something?

Was it not well worth while to ferret her way out from the old deserted building of Whitehall, and tо hide in that cool damp doorway, with the soft rain falling about her, to hear, even two words from his lips?

And so Bertha was better satisfied, for up to that moment he was perfectly safe, and he had not in any way or manner, from any mistaken kindness, deceived her as to his destination.

p. 146

The footsteps died away, and Bertha again held out her hands to catch the passing shower as she whispered to herself—

"He саmе this way, and this way he will return, and on his return his errand here will be over, and he will not be angry with me that I step out from this recess and tell him I have waited for him."

Yes, Bertha, be at peace, be happy, serene, and hopeful for a time, and we will follow those footsteps, the last faint echo of which no longer reaches your ears.

Captain Markham had reached St. James's a little before the time appointed for his interview with the king.

He did not think it either wise or prudent to seem to be excessively eager in seeking that interview, and so he had lingered for a while about the old purlieus of the palace before he made his presence known at any of its numerous entrances.

The experiences of the young officer concerning the intricacies of St. James's were not great. But there was a well-known door which everybody had seemed to recognise from time immemorial as conducting to what was technically called the "back stairs."

It was the entrance through which persons came who were properly accredited to have entirely private and what may be called domestic interviews with the king.

At five minutes before the half-hour Captain Markham presented himself at this entrance.

It was a perfectly smooth dingy-looking door, without knocker or other means of appealing to it. No doubt the thoroughly initiated had some peculiar way of tapping on its panels so as to procure attention.

Captain Markham, however, without such special knowledge, merely held his sword a few inches from its hilt and rapped sharply.

The door was opened instantly.

There was the rattle of arms as a couple of yeomen of the guard rose hastily from a wooden bench on which they had been sitting and resumed their halberts.

"I am directed to ask for Mr. Page of the Back Stairs," said Markham.

This formal address of the officials of the palace was then common. It may be so now, but fashions change. The page of the back stairs was called "Mr. Page," the words "Back Stairs" defining his special post, in that same way that another would be called "Mr. Page of the Presence."

"Mr. Page Back Stairs!" cried one of the yeomen.

"Mr. Page Back Stairs!" echoed a voice from some one whom Captain Markham could not see.

With a cloak thrown over him to shield him from the night rain, the royal page made his appearance rather abruptly and hastily through a baize-covered door.

"Who calls?"

"I would crave a word with you, sir."

The page looked scrutinisingly at Captain Markham, who, slipping from his finger the ring which the king had given him his his passport to the royal presence, held it up with an inquiring look before the eyes of the page.

"That is sufficient, sir."

"I am—"

"It is of no consequence, sir. His Majesty's private visitors have no names, or if they have they concern only his Majesty and themselves. Will you be so good as to follow me?"

"Certainly."

Captain Markham was very much surprised, however, to find that instead of being led at once into the interior of the palace he was conducted out again into the courtyard.

The cloak which the page wore might perhaps hare led him to the supposition that such would be the case, but he made no remark upon the singularity of the occurrence, and merely followed his conductor in silence.

It was then—that is to say, in a few seconds—that Captain Markham and the page passed the hiding-place of Bertha, and the royal attendant, being of somewhat a loquacious turn, made the remark the brief reply to which fell so pleasantly and happily upon the young girl's ears.

In rather a gloomy corner of the Colour Court there are two well-worn stone steps, conducting to one of the oldest looking doors of St. James's Palace.

In the smoothest, oiliest, and easiest possible way the royal page inserted a key into the lock of this door and opened it.

It conducted at once into a rather spacious octagonal, the remarkable feature of which was that the walls were thickly adorned with deer's antlers and weapons of the chase.

A square lantern hung by a long chain from the ceiling, and the rays of light that it cast about it were of the dimmest possible.

"If you keep close to me, sir," said the page, "it will be well, for there are several small staircases here about, and they are but badly protected."

The page as he spoke took from a corner of the hall a white wand some six or eight feet in length, to the top of which was tied a piece of wax taper.

Lighting the wax by the hall lantern, which the length of the wand enabled him to do, the page preceded Captain Markham, who was thus able to see his way tolerably well in the twilight sort of radiance cast about it by the small light carried by the page.

That the young officer was being conducted in some very private and secret way to the presence of the king there could be no doubt, but what was the motive for so much secrecy and troublesome arrangement he could not surmise.

Perhaps for a mere passing moment or so the word "assassination" may have suggested itself to Captain Markham, but he discarded the idea almost as readily as it presented itself, and scarcely permitted his hand to wander to the hilt of his sword.

Up and down several short flights of stairs, abruptly across a long gallery, entering at one door and making exit at another immediately opposite, Captain Markham followed the page.

And then they entered a spacious and richly adorned apartment, which evidently belonged to the more modernly habitable portion of the palace, and which, by the still smouldering remains of fire upon the hearth, seemed to have been recently occupied.

There was no pause, however, in this apartment.

Right through it, and out of it again by an opposite door, and so on through two others, went the royal page, until Captain Markham began to think that he was brought by this circuitous route on purpose to bewilder him.

Then the page came to an abrupt standstill.

He spoke in a low voice.

"I will announce you, sir, to his Majesty."

"You will say, then, that Captain—"

"Hush! sir, hush! There is no need if you entrust me with that ring."

"Certainly."

"His Majesty will not forget to whom he gave it."

"Take it, sir. I will wait your pleasure."

The next movement of the page was a very peculiar one, and Captain Markham looked with a wondering kind of interest and curiosity at his proceedings.

The room in which they were was of but moderate dimensions, and rather crammed with very costly furniture, very little of the woodwork of which could be seen, from the heavy coverings of dark crimson velvet.

Mr. Page of the Back Stairs placed the long wand with the wax taper at its end against a chair, so that it stood tolerably upright, and then, approaching a long narrow looking-glass that was set in the wall, commencing just above a narrow gold skirting and reaching about halfway up to the ceiling, he tapped sharply on the glass surface with the ring Markham had given him.

Then he turned round and made a gesture for Markham to be silent.

All was very still, and the silence of old Whitehall was scarcely more apparent to Captain Markham during his brief residence in it with Bertha than was St. James's at that time, although the home of the monarch and the court.

The page waited about two minutes, and then he rapped again upon the glass with the ring.

There was a dull heavy sound immediately on the other side.

It might be that some one had flung something against the wall, and yet it had something of the sound as if some heavy obstacle had been removed from the back of the mirror.

The page then stooped, and, pressing heavily upon a particular portion of the gilt skirting, the mirror flashed open, flinging out a bright light from behind it, and discovering the interior of a small apartment plainly furnished and evidently over-heated, for there was quite a rush of warm air from it into the outer room, and in which, at a table that was drawn curiously across one corner, sat the king.

A lamp was on the table immediately before the monarch, and there was a shade attached to it exactly in the shape of a green fan.

This shade was, however, so placed that it only availed the eyes of the king, while the full glare of the lamp was flung in the opposite direction—that is to say, in the face of any one who might be sitting or standing on the other side of the table.

CHAPTER XXIX.

ROYAL SECRETS.

The page knelt before the king, and held up the ring for his observation, just sufficiently high that it was possible to see it past the fan-shaped shade of the lamp.

"Ugh!"

Mr. Page of the Back Stairs seemed fully to comprehend that he had now received the royal authority to introduce the visitor to the king's cabinet.

He slowly retreated step by stер backward, and then whispered to Captain Markham—

"His Majesty will receive you."

The page then added in a lower whisper still—

"Your sword, if you please."

"My sword?"

"Yes. His Majesty never receives armed visitors."

"Nevertheless—"

"My dear sir, it is contrary to all etiquette."

"I am not an armed visitor. I am an officer of his Majesty's guard, and my sword is a portion of my uniform."

"But, really, my dear sir—"

"What? what? What's that?" cried the king. "What's that? Who's that?"

"I have the honour," said Captain Markham, as he stepped across the narrow threshold of the royal cabinet, and bowed profoundly, "I have the honour to present myself to your Majesty, in obedience to your Majesty's commands."

Markham had not parted with his sword, and Mr. Page of the Back Stairs was compelled to close the mirrored door without further insisting upon the point of etiquette.

The king glanced at Markham over the top of the fan-shaped shade, which, being of thin green silk, cast an awfully cadaverous hue upon the royal countenance.

"Our trusty and well-beloved Captain Weed Markham, of our royal guard, we are delighted to see you. Ugh!"

Markham bowed again.

"Well?" added the king. "We listen."

"I am here," said Markham, "according to your Majesty's orders, because I believe your Majesty has certain questions to put to me, which it will be my duty to answer, after which I have a request to make, which I shall trust to your Majesty's justice and judgment to grant."

"Hash! Oh! yes. Our justice and judgment may always be relied upon. Why are we here—here in this high position—here an anointed king—but for our justice and judgment? Ugh!"

Markham bowed again.

"We esteem, we admire, we love you, Captain Markham, and when we think what might have been the state of this realm but for you we tremble for England, for Europe. Captain Weed Markham, our well-beloved, we present you with—with—"

The king looked round the room, as though debating in his own mind whether Markham was to be presented with the window curtains, the chandelier, or a large couch that filled up one side of it.

"We present you with this snuff-box."

His Majesty dived into one of the waistcoat pockets and produced the same diamond-encrusted snuff-box he had previously presented to General Bellair.

It was a wonderful box, that. It did duty on many occasions, but, like the celebrated boomerang of the Australian aborigines, fling it where you would, it always came back to its owner.

The number of persons who had a vested interest in that snuff-box was immense.

"Yes, Captain Weed Markham, we present to you this snuff-box, as a testimony of our royal regard."

"I thank your Majesty."

"Yes, it is yours—yours, Captain Weed Markham—yours so soon as we can get another—and, in the meantime, whenever we take a pinch from it, we shall remember you and the little dramatic episode in which you really played so clever a part. Ugh!"

"Dramatic episode, your Majesty?"

"Yes. Ugh! ugh! ugh! He! he! he! Did you really think, Captain Markham, that we were in any danger beneath the roof of our old palace at Whitehall?"

"No, your Majesty."

"No? Eh? No? Why? why?"

"No, your Majesty, because I think that one loyal sword, wielded by one loyal arm, is equal to a host of traitors."

"But, our well-beloved Captain Weed Markham, there were no traitors."

"No traitors, your Majesty?"

"None whatever. It was a pretty little drama—a farce, man, a farce—a something to disturb the dull monotony of сourt existence. Ugh! We arranged it all with our beloved Frederick—our beloved Frederick, bless him! Our beloved— Ugh!"

The king took up a heavy glass tumbler which was on the table before him, and flung it right at the wall, where it was shivered to fragments.

"Bless him! Bless him! We feel as if we could break everything in our fatherly joy at having such a son Ugh! ugh!"

"Am I to understand your Majesty, then, that the service I thought I rendered you resolved itself into my being the innocent, dupe of a court jest?"

"Exactly. Nevertheless, we present you with this snuff-box, for we like innocent dupes who draw a single sword against fourteen traitors, with at their head the blackest fiend that— Ugh! ugh! ugh! Bless him! Bless him! But I'm afraid he won't live long. He is delicate. Bless him! he is delicate, and some thing I am sure will disagree with him some day. Ugh! ugh! ugh!"

"I am somewhat mortified, your Majesty, to hear from your royal lips that the service I thought I rendered you was, after all, only in intention, and not in fact. So now, your Majesty, I have a boon to ask—a fayour from a subject to a king—a fayour that subjects seldom ask, but which kings will find no difficulty in according."

"Well?"

"It is, your Majesty, that from this time forth the name of Weed Markham may be blotted from your

p. 147

memory. It is, your Majesty, that I may be forgotten.

"Are we to be ungrateful?"

"No, your Majesty. I ask the gratitude of oblivion."

"Kings never forget."

"But, your Majesty, the case is special. I am but the king's officer; I have no thought nor wish but to do my duty in the sphere to which fortune has called me; I have no mind nor liking for court intrigues, for cabals, or for factions. Bid me go in peace, your Majesty, and let there be an end."

The king shrank further back behind the lamp shade, and the green colour seemed to deepen on his face, for the lamp was waning, and the light it gave each passing minute was less than the preceding.

"Captain Weed Markham," he said, "before we forget you there is something that you must remember for us. You were called upon for a special service in our royal residence at Kew; you performed that special service like a loyal soldier; but there was a something—a something that happened—a communication that was made—and we call upon you, Captain Markham, as our subject—our special subject, because our officer—we call upon you to say what happened after you passed out of a certain window of our palace at few along with, or immediately on the footsteps of, a certain personage in scarlet."

Captain Markham was silent for a few seconds. the king glared at him out of his green-looking eyes.

"Speak!" he yelled. "What happened?"

"I am not here," replied Markham in low tones, "but with the intention of candidly imparting all to your Majesty that has over reached my ears. But—"

"But what? What, man? What?"

"Shall I feel that I have your Majesty's royal assurance that then my request shall be granted, and that for all further time I may be considered as one no longer associated with this state secret, which will never pass my lips and may rest in your Majesty's own breast?"

"Assuredly—assuredly—and rich reward—rich reward—"

"No, your Majesty, no."

"Rank and wealth. Why—why—why, Captain Weed Markham, we began well. Have we not already presented you with our royal snuff-box? Speak! man, speak! What happened? Tell us all."

"Oh! your Majesty, retract some of your words. I seek not for honours and distinctions upon such a basis."

"Well, well, be it as you will, be it as you will. If you court obscurity you shall have it; but you will still be the king's friend, the king's friend. Not a bad title that! the king's friend! Now go on. We listen."

"At your Majesty's express orders, a sergeant's guard—I speak as regards the number of men—a sergeant's guard, under my command, fired a volley through a certain curtain at Kew."

"We heard it. Pass on."

"The curtain fell, and there appeared a wounded man—"

"In scarlet."

"Yes, your Majesty, in scarlet. Sick, faint, and dizzy with his wounds, he reeled to a window, passing through it. Sword in hand, I followed him."

"And killed him?"

"No, your Majesty. The bullets of your guard had already done their deadly work. I caught him in my arms in the garden, and there, beneath the moonlight, in less than three minutes' time he breathed his last."

"But—but during those three minutes he spoke—he spoke to you?"

"He did."

"He told you something?"

"He did."

"He whispered to you his secret—the secret of his life—the—the—the secret of his death?"

"He did."

"Well, well, well?"

"He said, your Majesty, that—that—"

"Well, well, well?"

"Your Majesty may call it treason."

"Tash! man, tash! Nothing can be treason that the king commands. Out with it! What was it? Speak! man, speak! Are you blind, deaf, dumb?"

"No, your Majesty. This man, who called himself 'A Mystery in Scarlet,' whispered to me with his dying breath that your Majesty's father was Elector of Hanover."

"Rare news!" shrieked the king as he clapped his bony hands together. "Rare news that! Well, well?"

"He further stated that the elector, your father, was married to Sophia, daughter of the Duke of Zell."

"Our gracious mother. Ugh! ugh! ugh! Our gracious mother. Well?"

"But that previously to that he was married to one Bertha, a younger daughter of the Count Coningsmark—"

The king sprang to his feet.

"And that by that marriage he had a son."

"Tash!"

"I do but repeat, your Majesty, what was related to me in gasping whispers by the dying man."

The King sank back into his chair again.

"Go on, go on."

"He further stated that this Bertha—the real Electress of Hanover, by her marriage with your royal father—was kept in secret at the Schloss at Aubergern, and that when the Count Coningsmark protested too much one day he was—"

"Well, well?"

"Murdered."

"Ugh! People should not protest too much. Go on, our beloved Captain Weed Markham, go on."

"He further stated that upon your royal father's marriage with Sophia, daughter of the Duke of Zell, with whom he received a portion of one million sterling, Bertha of Coningsmark was still alive."

"Ha! ha! ha! He! he! he! Ugh! ugh! ugh! Rare news! Rare news! Why, then—we—we—we are illegitimate, and our dear Frederick is worse than that. Don't kneel to us, man—don't bow to us. Who are we? Nothing, nothing. Ugh! ugh! Worse than nothing. Go on."

"He further stated, your Majesty, that the son of Bertha of Coningsmark still lived."

"Lived?"

"Yes; although then expiring, with twenty mortal murders on his head, with the bullets of what should have been his own royal guard plunged hot and scathing in his breast, he told me that he was the man—the legitimate royalty of England."

"Go on. Well?"

"And then he breathed his last."

The king clutched the table until it shook again.

"And what—what, Captain Weed Markham, did you do with the body?"

"I left it there, your Majesty."

"You left it there?"

"As Heaven is the judge of men and kings, of innocence and guilt, I here aver and swear I left it there."

"Ugh! Have you told us all?"

"Not quite. He said that state papers confirmatory of his story—so sad, so mournful, and so blood-stained in its end—were to be found in a certain cabinet in a chamber of old Whitehall Palace which in the time of Charles the First went by the name of Rupert's Room."

"Is that all?"

Markham was silent.

"Is that all, trait—we mean our well-beloved Captain Weed Markham?"

"No, your Majesty. There was a young girl whom your Majesty saw with me at Whitehall."

"His daughter!" yelled the king. "I knew it. Tash! bash! curse! His daughter! Will they never be extinct? Son's daughters—daughters' sons' breeds? Smash her!"

"Your Majesty?"

"Our dear Captain Weed Markham—ugh! ugh! ugh! —we are old, our blood is thin, and we lack the fire of youth. But you—ugh! ugh! ugh! —you—eh? —you love this little girl? Ugh! ugh!"

"In a sense, yes, your Majesty, but in another sense, no. I love her, that she is fair, and young, and gentle, and ingenuous—a thing of tenderness, simplicity, and truth. I love her as I love a star, a cloud, a flower. My life is hers, to stand between her and all harm, for to me she has been a legacy from the dead, who on that awful night looked into my eyes and would not call me murderer, because I had but clone a terrible duty. I do love her as a reflex here on earth of one of Heaven's angels. I do love her, and while Providence shall grant me life and strength I will protect and love her still."

CHAPTER XXX.

A COURT-MARTIAL.

The king seemed to shrink back into a smaller and yet smaller compass as Captain Markham spoke, until there was little of him left except the dim shadow of that shabby piece of old royalty.

The silence was prolonged and almost painful to Markham, who broke it by saying—

"I have now told your Majesty all. The truth or the falsehood of these statements I have nothing to do with, nor do I feel myself called upon in any shape or way to verify them. Along with the secret of that poor Mystery in Scarlet I by no means adopted his obligations."

The king coughed.

"And if it be true that uneasy lies the head that wears a crown, I need not covet one, through crime, intrigue, and bloodshed, for that young girl who is thrown by accident upon my protection and my bounty."

"Yes," murmured the king, and as he spoke he seemed to forget that he was not alone.

"Yes, uneasy lies the head that wears a crown. My head has been always uneasy, and always will be. There are the Jacobites, there are the Irish, there is Frederick. Oh! yes, it is very true, uneasy lies the head that wears a crown. She need not covet it; but, as I have it, I mean to keep it. And what a precious tale this would be for all my enemies! And I have many. What a precious discovery that, in a little white-faced girl, soft, tender, and delicate as the first shoot, of a spring flower, they might hail the Queen of England, while I—ugh! What would become of me? Illegitimate! Not even the Electorate of Hanover to fall back upon! They call me a Hanoverian rat. I have heard the rabble in the streets yell it after my coach. Ugh! There would not be a rat-hole even in Hanover for me to creep into. There is but one pleasure, one delight. Frederick! Ugh! ugh! What would become of Frederick? I am almost inclined—it's worth thinking of—I am old, and how grand it would look in history if I were to take her by the hand and play the high rôle, the noble dignified part, and proclaim her! Ugh! ugh! ugh! What would become of Frederick? Ugh! ugh! ugh! No, I can't do that—I can't walk that way—I am knee-deep in her father's blood, and it thickens about me and clogs my footsteps. No, no, no, no."

"Your Majesty."

The king uttered a yell.

He awakened from his terrible reverie to find that he was not alone.

"Your Majesty, I feared—"

"You feared? Wretch! what did you fear?"

"I feared your Majesty was not well."

"Not well? How dare you say we are not well? Do you compass the demise of the crown, sir? It is treason! treason!"

"Your Majesty?"

"Treason! we say, treason! Wretch! Is this the meaning of the sword by your side, contrary to every etiquette of our court, and every other court? Are we to be murdered in our own private cabinet?"

"Your Majesty strangely misjudges me."

"Wherefore that sword, then, sir? Wherefore that sword?"

"It belongs to your Majesty. I wear it as your officer; but if your Majesty desires it I surrender it, and here on my knee I tender it to you."

Captain Markham drew his sword, but the moment the blade was well clear of the scabbard the king with one blow of his hand dashed the lamp from the table with a loud crash, and yelled out at the top of his voice—

"Treason! treason! treason! Help! Treason! Treason!"

Captain Markham did not attempt to re-sheathe his sword, and if he had amid the darkness he could not have accomplished it, but he stood like one bewildered, wondering what this sudden rage of the king could mean.

"Lights! Lights!" still yelled the king.

"Lights! Are we deserted? Treason! Treason!"

There was a rush of feet.

A violent dashing open of two doors.

A blaze of light.

And then Captain Weed Markham found himself violently seized by a tumultuous throng of pages, yeomen of the guard, grooms of the household, gentlemen in waiting, and other officials of the palace.

His drawn sword was wrenched from his grasp—indeed, he did not seek to retain it, nor, beyond the natural impulse to shake off the too rude hands that laid hold of him, did Markham make the slightest resistance.

He looked about him from face to face, and seemed more like a man in a dream than in his waking senses. the incidents of the last five minutes had taken him so completely by surprise that he had not time to understand them.

"That is well," roared and spluttered the king in well-affected passion. "That is well, yeomen and gentlemen all. We owe you our life, which this arch-traitor would have taken, here, in our own private cabinet."

"Your Majesty!" exclaimed Markham. "Your Majesty knows the falsehood of this charge."

"Traitor! Do you give your king the lie?"

"Your Majesty, I—"

"Silence, wretch! Who—who of all of you, gentlemen, saw his drawn sword in his hand?"

"All! all!" cried a chorus of voices

"But I drew it," exclaimed Markham, "to present it to the king, and at his own request."

"Oh! arch-traitor! Oh! hideous subterfuge! But we demean ourselves. We step from the height of our royal dignity to parley with an assassin. Oh! ingratitude! ingratitude! There is the thing, yeomen and gentlemen all. the villain tried to take us at unawares, as we were presenting him with our royal snuff-box."

"This is infamous, sir! And were you ten times a king, instead of being the—the—"

"Choke him! Kill him!"

"I will not utter the word, say what you will, king as you are in fact, although most unkingly in mind. I am in the toils, I have entered the wolf's den, and am already torn and bleeding. You and I, king as you are, may never meet again; but in the majesty of right, and in that eternal fitness of things which is the heritage of Heaven to man, there will come for you a day of retribution."

"To the Tower! To the Tower!" shrieked the king.

"I commit him to the Tower."

"Your Majesty — my gracious lord — my worthy master—viceregent of—of everything on earth—"

Norris, who had come in with the throng, plumped down upon his knees with a fearful thud just before the king.

p. 148

"What now?"

"Oh! my royal master I we'll have a day of fasting and humiliation—I mean a thanksgiving —for your royal preservation, and I, even I, my gracious master, the meanest of your subjects, the mere worm —the wormiest of worms—I beg to suggest—"

"What, Norris?" The king gave a hideous grimace, which was meant as a gracious smile. Norris had learned his lesson well. He had a part to play, and this was it. The word "Tower" was his cue, and so he had spoken, and so on he spoke.

"My gracious master, this black and ugly villain, this traitor, who would have taken your Majesty's wonderful and gracious life, is an officer—"

"Ah!"

"An officer in your Majesty's guard, of which your Majesty is by gracious Providence the chief and head, and so—and so, your Majesty—"

"Ah! ah!"

"And so, your Majesty, he has drawn his sword upon his superior officer."

"Ah!"

"Which is an offence to be tried forthwith, within the hour, by court-martial—"

"Ah! ah!"

"Composed of such officers as may on the spur of the moment be found in the palace. There is General Bellair, for its president; there is Colonel the Marquis of Charlton, for one of its members; there is Mr. Ogilvie, a worthy subaltern. Oh! your Majesty, with the anointing oil upon your royal head, which is never dry, by a dispensation of Providence, I, your meanest subject and worm, venture to suggest that this arch-traitor, this ugly cutthroat, this ravening beast in the shape of man, be tried at once by a court-martial."

"Ugh! ugh! ugh!" chuckled the king, as he dealt heavy blows on the top of Norris's head with the sharpest corner of the snuff-box.

"Ugh! ugh! ugh! It is not so bad a thought, after all."

"Oh! your Majesty, tears of gratitude are in my eyes that you should think the humble suggestion of such a worm as I am worthy of—oh dear!"

Tears were certainly in Norris's eyes, but they arose from the agony he endured in consequence of the raps of the sharp edge of the snuff-box, and the "Oh dear!" was forced from him by a sharper rap than usual.

"We are always open," said, the king, "to suggestions. Heaven forbid that our mind should be closed against a happy idea, even from the—the—"

"Meanest," put in Norris. "Well, the meanest and—and—"

"And most contemptible worm," added Norris.

"Exactly," said the king. Norris glanced upwards and saw the snuff-box coming down with redoubled force, and he dropped flat to the floor, wriggling away very much after the fashion of the worm to which he likened himself.

"Our mind is made up," said the king. "It is our pleasure to consider this a military outrage. Let General Bellair be summoned to our presence, and our good yeomen of the guard here will surrender their prisoner to a sergeant's guard of the ordinary troops."

Markham began to see his danger.

Danger immediate and terrible.

And yet it was not of himself that he thought.

It was of Bertha.

Of that young, innocent, helpless girl, waiting for him, as he believed, in those old silent gloomy chambers at Whitehall.

Waiting for him whom she might never look upon again.

Waiting, listening, and watching, until the heart grew sick with its own agony.

Oh! if he could have had voice sufficient to cry aloud to her to fly! for now he felt he knew all her danger.

And he—he had compromised her by his foolish confidence and hope in that king who never forgave an enemy, never trusted a friend.

Surely, oh! surely the bitterness of death was then and there present in the heart of Captain Markham!

He seemed to see, as in a vision, that young girl waiting and listening until the red-handed murderers came to take her life.

He seemed to hear her shrieks—shrieks in which his name was embodied—and he was helpless—helpless by his own folly—trapped, snared, murdered, and none to save her.

He was desperate.

He was maddened.

There was a wild fire in his eyes.

He felt the strength of a hundred men in his arms.

Surely life—escape were worth one struggle.

He made it, and he made it in vain. The tumult was prodigious, but, torn, bleeding, and vanquished, that poor heart was still in the toils, and all around it looked bleak, stormy, and despairing.

(To be continued in our next.)