A MYSTERY IN SCARLET.

by

Malcolm J. Errym,

Author of "Holly Bush Hall," "George Barrington," "Edith the Captive," "May Dudley," "Sea-Drift," "The Marriage of Mystery," "The Treasures of St. Mark," "The Octoroon," "The Court Page," "Secret Service," "Nightshade," "The Sepoys," &c.

CHAPTER XL.

BERTHA'S DESPAIR.

It was not death, but something so nearly resembling it that sat upon the pale face of Bertha, when she was laid upon a couch, in Agnes Bellair's apartments, that both the latter and Lucy Kerr regarded her with as much pity as admiration.

Bertha was very beautiful even at that moment of depression, and when the little life that remained to her seemed only lingering as though loth to leave so fair a dwelling.

The shock to her delicate organisation was far greater than that which Captain Markham had received, and but for a slight flutter at her heart, both Agnes and Lucy might well have believed that they looked upon at least one victim of the state policy and evil passions of the king.

Who or what she was they had not the most distant idea. It was sufficient, however, for them that she was human, like themselves, and that she required aid, support, and possibly protection.

And then they were certainly acquainted with one fragment of her history. It was but a fragment, but there it was.

There it was, standing out brightly and beautifully from the great throng of human frailties and human selfishnesses.

Had she not shown her willingness and wish to die for or with another?

This might be romantic, but it was something after the manner of feeling of both those young girls. It was the touch of nature which made them feel akin to the drooping fading flower which lay before them.

And that was just what Bertha looked like.

Some fair lily roughly broken from its stem, and perhaps somewhat drenched and fluttered by a storm, but, although losing the pride of its full health and vitality, still most beautiful.

It was a strange revolution that had taken place in the mind of Agnes Bellair—a revolution which only dated back an hour or two.

She was not jealous of Bertha.

Time had been, when Captain Weed Markham was the idol of her heart, when she believed that he stood alone amid all humanity for grace and nobleness, she would have felt heart-stricken at the idea of any one but herself clinging to him in the hour of danger or of death with such a full devotion.

But she had been inexperienced.

She had made the common error of youth in believing that the first fancied piece of excellence met with was the only one in existence.

As a converse of the proposition, she would likewise have readily believed that the first cruel treacherous nature she encountered must be altogether exceptional, and by no means a common type of humanity.

And so, as we say, Agnes Bellair was gathering experience and a knowledge of human nature.

The true nobility of soul which had characterised the Marquis of Charlton summed itself up with his undoubted devotion for her, and from that moment she loved him.

It was a logical consequence, from which there was no escape—not that she tried to escape from it, or made it in any way a matter of reasoning.

She really now loved the young and gallant marquis with all her heart, and the extreme satisfaction of the case was just that she could at any moment appeal to her reason to side with her feelings and sanction the preference.

Therefore was it that Agnes Bellair felt no pang at the sight of the rare and delicate beauty of Bertha.

She could not but conclude that the young girl she saw before her had accompanied Markham to the palace.

It was not within the limits of probability that their meeting in the Colour Court was accidental.

No. It was a love passage altogether, the entire and perfect devotion of one heart to another, arising from the perfect feeling and understanding of affection between them both.

And she had nothing to complain of.

Markham had broken no vows to her. All was well; all was well.

How happy she wished him, along with that delicate and tender sentiment which would never wholly leave her, that she had been deeply interested in his fortunes!

"How pale she is!" whispered Agnes to Lucy Kerr. "She is, indeed. This is very sad. I cannot comprehend it. The whole affair is so mysterious, and we have already heard so little, except the prominent facts, that I long for a full explanation."

"Hush! She moves." A low moan came from the lips of Bertha. Both the young girls bent anxiously over her, as she seemed struggling to speak.

"Help! Help! The fire! The fire! Oh! where will he look for me when he returns? I must needs remain here, for you will not tell me that my father is no more. Help! Oh! help!"

"There is no danger," whispered Lucy Kerr. "There is no danger, indeed."

"No danger?"

"None whatever. You are safe—safe now."

"Safe?"

"Yes, and with friends. Believe me, all is well."

Bertha looked about her with a strange expression.

Everything was so new to her.

There was not a single object that met her eyes with which she was familiar.

And then she looked at Agnes and at Lucy, in dreamy wonder as to who they could possibly be.

She was making great efforts to remember—to remember that past which had been so rudely jostled into chaos and confusion in her brain by the terrible moments she had passed in the Colour Court.

The effort for a few minutes seemed to be in vain. She could not separate one incident from another, and the manner in which they mingled together made it quite impossible for her to determine which were actual and which were purely imaginative.

So much had happened to her within the last few days—so much that was strange, wonderful, romantic,

p. 210

and out of the common order of things—that she now found herself mixing them up with the wild incidents of the old chivalric romance she had been reading when all alone she waited for her father in that dreary old house in Westminster next to the Red Cap Inn.

Both Agnes and Lucy saw the state of mental confusion which their young and fair visitor was in, for Bertha's face was like a summer sky, over the clear depths of which every passing cloud was visible.

"Believe me," said Agnes, "that you are quite safe. We have both the will and the power to befriend you. Look at us, and if you have enemies you will see that we are not of them."

"Will you tell us who and what you are?" asked Lucy.

Bertha still looked from one to the other confusedly. Then she spoke in very gentle, low, soft accents.

"I must go back. I must go back."

"Nay," replied Agnes. "You are fit to go nowhere. Remain with us yet for a time in peace."

"I do not mean that," replied Bertha, "I mean that I must go back in thought, and so from that past time reach the present. I feel confused and weary, and know not what has happened; but it is something terrible."

She put a hand over each of her eyes.

To think back as she wished, it was necessary to shut out external objects.

And then, while Lucy Kerr and Agnes Bellair regarded her with fixed and compassionate attention, they heard her in low tones murmur to herself—

"Waiting for my father. Waiting for my father. Waiting all alone, as I had waited often alone, with Heaven and my own thoughts, which flew after him, carrying my affection with them, to wrap him round about in panoply of steel, and shield him from all harm, ever and ever. Alone—alone—and then some noises —robbers, assassins. Then the pistols—those weapons he left with me for my defence in any dire extremity—the sharp report, and then— what then? The fire, the thick pungent smoke, the red flames. But he was there and saved me. How the waters of the Thames lashed our frail boat with fury! Surely we are lost. No, not yet. There is a talisman which forms the essence of true affection, and it will save us. Yes, that is it—affection. It may be the bud, the leaf, but it is not the blossom. What happened then? That old palace, with its stately chambers, so peaceful, so serene. A king? He a king? That a king of nations? Let me think. Onward, onward still. O Heaven, no. What is it? Where do I follow him unbidden? Where do I wait for him? The soft rain falling in that dismal court. See! he comes! he comes! They will kill him! Murder! Murder! My life for his! What would you more? A life for a life! Welcome, death for him or with him. No. O Heaven they have killed him! and I live yet! I live yet!"

The shriek that burst from the lips of Bertha must have been heard far and wide in old St. James's.

It was in vain that both Agnes and Lucy strove to calm the wild frenzy that took possession of her.

Indeed, they were both so alarmed and agitated at the moment that they omitted to say the one thing which she might have heard, and which might have calmed her.

They should have held her in their arms.

They should have constrained her to listen, in spite of herself. They should have called aloud to her, in endless repetition, until the words pierced through all the excitement of her brain, and sank into her understanding, Markham lives! Markham lives!"

But they only strove to detain her. In that effort they impeded each other.

They implored her to be calm and still, but they forgot the element of calmness and of stillness that would have been contained in those few words, "Markham lives! Markham lives!"

And so she broke from them.

Broke from them with the strength of despair.

She filled the air with her cries.

It was terrible and awful to hear the word "Murder!" uttered in such tones by lips like hers.

"I must seek him! I will seek him! With him ever still, alive or dead! I know it all now! They have killed him! killed him! Murder! Murder!"

She tore herself from the detaining grasp of Lucy.

She reached the door.

She escaped into the corridor beyond.

Whither would she fly?

What danger might she not encounter in that gloomy old pile, inhabited as it was by at least one person who would not scruple to seek her destruction?

How was her presence to be accounted for in St. James's?

What a host of new dangers and complications might arise from this headlong flight of Bertha through the palace!

Agnes and Lucy pursued her.

In vain they cried out to her to pause.

She heard them not.

The echo of her voice filled up her entire perception.

"Murder! Murder! Murder!"

That was the incessant cry.

And no doubt the one idea was to seek Markham, alive or dead, and the dominant notion in her mind was the cruelty that had been inflicted upon her by a separation from him.

There was something very strange and wonderful about the manner in which Bertha made her way through the palace, opening the doors that she had never seen before, flying along galleries, corridors, and through apartments of which she could have had no conception.

The frantic notion no doubt was to get out into the courtyard again, and there rejoin what she believed to be the lifeless body of Markham.

But so wild an access of excitement must soon have its end.

The gentle voice of Bertha must soon subside into inarticulate hoarseness beneath such cries.

And now there is a gallery crowded with glittering arms.

Now there is a door loaded with barbaric gold and panelled by mirrors.

She speeds across that gallery like some belated spirit.

She opens that door.

She dashes aside a heavy velvet curtain, all dazzling crimson and bullion fringe, which is some few paces beyond it.

And then her strength fails her.

She staggers, rather than walks.

She no longer cries "Murder!"

She nearly falls, but Agnes clasps her in her arms and saves her.

"Alas! alas!" ejaculates Lucy Kerr. "This is dreadful. All this will kill her."

"Poor girl!" said Agnes. "She faints."

"Oh! Agnes. Is it death?"

"Do not say so, Lucy, do not say so. Where shall I place her?"

"Here, here. Let her rest."

"Where are we?"

Both Agnes and Lucy looked about them, and a feeling of awe crept over them, for they were in a portion of St. James's which they had never seen except upon the highest state occasions.

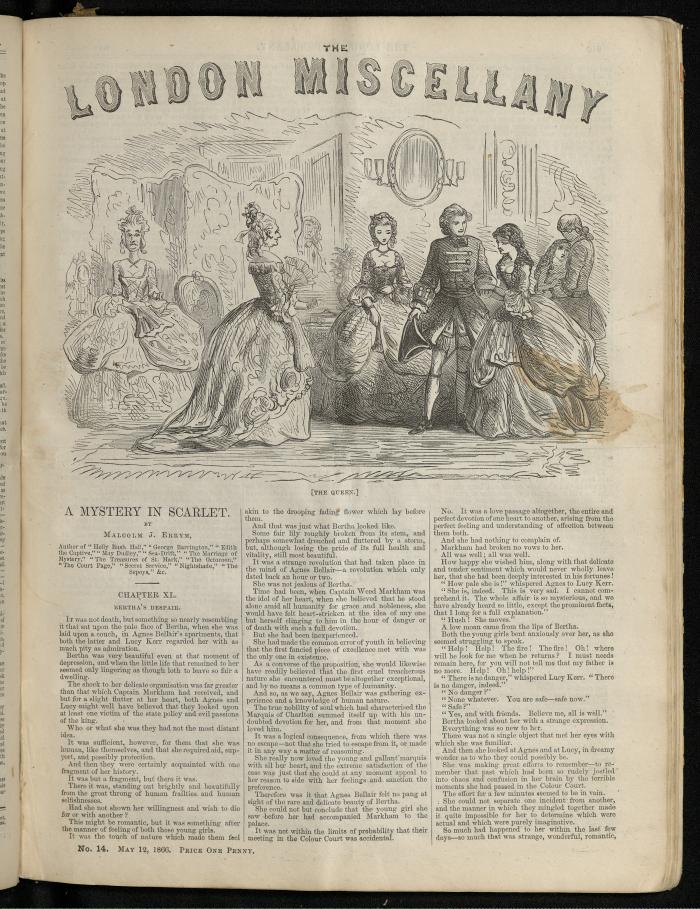

It was the new throne-room, the actual presence-chamber, upon which the king, in a freak of unusual munificence, had recently expended the sum of forty thousand pounds, and which, according to a whim of his own, was always kept dimly lighted, in order that he might please himself, whenever the fancy took him, by visiting it and pretending to deprecate all its adornments and regal grandeur.

And it was the actual throne of his Most Gracious Majesty King George the Second to which Agnes Bellair half led and half carried Bertha, and upon which she placed her tenderly.

And then Agnes, whose feelings had been wrought up to the highest pitch of sensibility by that terrible chase through St. James's, must needs now give way all at once, and kneeling at the feet of Bertha, she let her head droop upon the young girl's lap and burst into tears.

"Agnes! Agnes!" cried Lucy. "How foolish, how criminally foolish we are! She loves Markham—he is her whole soul, her life—and she needs but to be assured of his safety to be herself again."

Agnes still wept bitterly.

"I think she is really dead, Lucy."

"No, no, no. This grief is terrible, but it has not killed her, and not having killed her, joy will be her restoration."

"What shall we do?"

"Hush! I will speak to her. Can you hear me? Let me know by the slightest movement that you hear me when I tell you that Markham lives! Markham lives! Markham lives!"

Bertha made no sign.

She was past hearing even those words.

"We must recover her," exclaimed Lucy. "This is terrible. Do you know, Agnes, if Sir Hans Sloane is in the palace, or any other of the queen's physicians?"

Agnes shook her head.

"You stay with her, then, and I will go and see."

"No, Lucy; no, Lucy. Do not leave me. What if the king should come here?"

"The king?"

"Oh! yes, Lucy. Then, indeed, we should be lost! lost! His violent temper, his rage, probably now fully awakened at the escape of Markham—for do you not recollect the Marquis of Charlton said that the king—"

"Hush!"

"What? What?"

It would almost, seem as if the name of the king had been a kind of invocation, not to produce that monarch himself (for he was at that very moment lying prostrate in the dark in old Whitehall), but to call for the next noticeable person in the realm.

A small side door was flung open, and rather a comely-looking lady, at lived in plain lavender silk, with a rich lace scarf tied in a slovenly manner about her throat, entered the throne-room.

"Her Majesty the Queen!" said Lucy Kerr, as she curtseyed very low.

CHAPTER XLI.

THE PRESENCE-CHAMBER.

Queen Caroline was tender-hearted enough, and she had seen trouble enough, as the wife of such a monarch as his Majesty George the Second, to either sympathise or be impatient at other folks' woes.

She dearly loved, however, anything in the shape of plot or mystery, and she had that kind of reputation which belongs to many good-natured people of being a determined match-maker.

Her Majesty was quite alone, and must have strayed into the throne-room more from vacuity of mind and want of something to do than from any actual purpose.

The look of surprise with which she regarded Lucy Kerr and Agnes Bellair had something almost comic in it.

But that look soon changed to one of coldness, with a spice of anger in it.

It so happened that the kneeling attitude of Agnes and the low curtsey of Lucy Kerr seemed to the queen as though they both applied to the young girl who actually occupied the throne.

"Indeed, ladies!" said the queen, with her strong German accent. "Indeed, ladies! So this is his Majesty's last? Why what has become of the Duchess of Kendal?"

The angry look on the face of the queen was rapidly depriving her of all that innate grace which in real truth still belonged to her.

"I am much afraid," she added, "that I interrupted some little court ceremony; but it is something new to me that the ladies of my household should lend themselves to such—to such—"

The queen could not find a word sufficiently strong and full of moaning to express her indignation.

"Madam," commenced Lucy Kerr. "Gracious madam—"

"Silence, minion! silence! At least you and your companion shall not witness the humiliation of your queen."

And now, if Lucy Kerr had not taken the initiative, and almost done a rude thing, the queen would have left the throne-room under some impression that it would have been impossible ever to eradicate.

"Madam," exclaimed Lucy, "I implore you to believe me that there is nothing which we so much dread as the appearance of his Majesty here."

"Eh?"

"Yes, madam, we fear that such an appearance would be full of danger to those who sincerely love, and who might otherwise effect a happy reunion."

This was touching the queen on the tender spot of her heart. "What do you main, Miss Kerr?"

"There are two young lovers, your Majesty."

"Oh!"

"And this is one of them."

"Ah!"

"And his Majesty seeks to separate them, even by death, if no other means present themselves."

The queen advanced two steps towards the throne at once.

"And who may this young person be?"

Lucy Kerr looked at Agnes, and Agnes at Lucy Kerr, for that was just the sort question they could neither of them answer.

There was nothing for it, however, but absolute candour, and Lucy spoke in a calm respectful tone. "Madam, I regret to inform you that we do not know who this young person is, but we do know that his Majesty has sought this night the destruction of a young officer of the guard to whom she is deeply and sincerely attached."

"Ah!"

"And that the state in which your Majesty now sees her is brought about by the belief on her mind that the destruction of the young officer has been accomplished in the Colour Court below."

"Shot?" cried the queen.

"Yes, your Majesty, after a mock court-martial on some vague charge, which was merely meant to give a colour to what was really a murder."

This was a bold speech from Lucy.

A speech which, it repeated to the king, or heard by any of what was called his party, would have been quite sufficient to dismiss her from the palace at once, and put an end to all her court career.

But Lucy know she had the queen with her.

She could see into the royal mind perfectly well, and had no difficulty in clearly understanding the sort of interpretation which the queen would put upon the king's part in this business.

Of course he wanted to shoot the lover because he was enamoured of the mistress.

That was it.

The queen never doubted this for an instant, and, although Lucy Kerr could see perfectly well the error into which she fell, it was one so important to the safety of Bertha and of Markham that she felt quite justified in leaving it alone, and not going out of her way to correct it.

"We heard," said the queen, "a discharge of fire arms."

"Yes, your Majesty. That was the attempt to kill the young officer."

"The attempt?"

"Only the attempt, your Majesty. It failed because the agents employed to carry it out had not the heart to do so."

"But how?"

p. 211

"Oh! your Majesty, they omitted the bullets in the cartridges, and so the young lover is safe, and we wish to recover this girl and tell her so. And so your Majesty will perceive that if the king should find all this out—"

"It is not necessary," interrupted the queen, "to say more. Who am I, that I should not protect those who confide in me, and who really wish to be united, and who resist the evil desires of the—the—"

The queen did not say " king:," but those who heard her were quite able to supply the omission.

"You will go, Miss Kerr," she said, "and tell Maria Bentinck to bring here some of my strong waters. Poor young thing, they will soon restore her. And where is the young officer? Who is he? Do we know him?"

"His name is Markham, your Majesty."

"Markham? Markham? We fancy we have heard the name. But pray be quick, Miss Kerr, for the strong waters. Why, she is very young! You look quite ill, Agnes Bellair. You will have to go to Hampton Court and recover yourself."

"I thank your Majesty; but I am sick with apprehension."

"Apprehension?"

"Yes. If his Majesty should arrive—"

"And who are we?" exclaimed the queen. "Who are we that we should mind who arrives? But we will not remain here. The place is frigid and cold. We will go to our own private cabinet. See if that young thing can be roused to walk. We should like to see the young officer. It would be our pleasure to bring them together. What would hinder the Bishop of Peterborough from uniting them in the private chapel? But she is very young, and now I look at her I fancy she looks younger still."

"Von strong vaters," exclaimed Lady Grumpsch, who appeared, instead of Maria Bentinck, with a square Dutch-looking bottle, from a shelf in what was called the queen's oratory.

Agnes Bellair succeeded in forcing a small portion of the stimulant between the lips of Bertha, who, with a deep sigh, opened her eyes. Lady Grumpsch then assumed an oratorical attitude, and, addressing herself to the queen, spoke in a high cracked tone—

"Please, von Majesty, von great scandal. Officers and mens—young mens and officers—goes abouts vith maids of honour, and von says von ting, and you says oder ting, and no von is safe. I am full of apprehend mienself, and shall double door von look in von middle of von night, and let everybody in as comes."

"Lady Grumpsch," said the queen, "we know all about it."

"Yah?"

"Certainly, and we take the whole affair into our own management. There is a young couple to be married, and—and—and the king—that is to say, a court-martial—and an officer—dear me! all this is almost too much for our poor head. We shall have to send for Sir Robert. That will be the end of it. We shall have to send for Sir Robert."

"Hush!" said Lucy.

She was so deeply interested in the gradual recovery of Bertha, and in listening to catch the first accents of her voice, that she forgot the serious breach of etiquette she was making by saying "Hush!" to the queen.

But her Majesty fell as interested as Lucy Kerr, and likewise forgot all her dignity in her anxiety to know what was going on.

"What is it all?" asked Bertha faintly.

Then Agnes was determined there should be no farther lapse on her part in giving the desired information.

She bent forward very close to Bertha as she spoke—

"I assure you," she said, "in all truth and honour, and by every hope I have here and hereafter, that Captain Weed Markham is perfectly unhurt and well."

Bertha heard that.

What a change there was!

The wan startled look passed away from her face like a cloud.

She stretched out her arms and folded them about Agnes's neck.

There was no need for speech.

The thankfulness—the abounding thankfulness—of the look was more than enough.

"You remember it all?" added Agnes, speaking thickly with emotion. "You remember it all?"

Bertha nodded.

"There were no bullets."

"No bullets?" she repeated faintly. "No bullets? Oh! if there had been bullets! They must have been more merciful than that cruel cruel king."

"Hush! hush!"

"Dat vas treason in von high," exclaimed Lady Grumpsch. "I shall make grand report."

"No," said the queen. "There will be no reports made. Whatever has happened here, and whatever has been said here, will never be reported, or oven spoken of, by any one who has the least pretensions to be called the friend of the queen."

Lady Grumpsch staggered back until she reached one of the heavy velvet curtains that masked a door way, behind which she disappeared; but a strange gurgling sound proceeding from that place of concealment sufficiently testified that she was consoling herself with the square bottle of strong waters which she had taken with her.

"Come, now," said the queen. "I dare say this young girl can walk. We will go to my private cabinet and be free from all possibility of interruption. I am afraid I shall have to send for Sir Robert, for I am beginning to feel quite confused already, and he knows everything."

"Where is he?" asked Bertha of Agnes, as she still held her round the neck.

It was a strange thing to see Bertha, who had been the unconscious rival of Agnes, while Agnes had filled the same position as regards her, clinging round her neck as to her best and most steadfast friend.

But it was from Agnes's lips that had come that blessed assurance of the safety of Markham, and with her would for ever be associated the expressions which might almost be said to have snatched her from death to life.

"Oh! he shall be taken care of," said the queen. "Rest contented, my good girl, on that head, for you need no longer have any fears of a certain person."

The queen nodded significantly, but Bertha had no more idea of what she meant than if she had alluded to the geography of the moon.

With the assistance of Agnes, Bertha was able to follow the queen, and a very few minutes sufficed to place the little party in that private cabinet of St. James's Palace which the queen called her own, and which only upon very rare occasions was intruded into by the king himself.

Bertha was rapidly recovering.

The delicate colour that had entirely fled from her cheeks was slowly creeping back again.

It was something of a shock, however, to her to find that she was actually in St. James's Palace, and in the presence of that royalty of which she had a confused recollection that her father had spoken strange, mysterious, and disparaging things.

It was impossible to resist, however, the homely kindness of the queen, who every moment became more delighted with the idea of actually bringing two lovers together, while at the same time she believed she foiled one of those precarious and evanescent fancies of the king of which she knew too much.

CHAPTER XLII.

THE QUEEN'S CABINET.

Lucy Kerr did not feel herself justified in stating clearly and distinctly even to the queen that it was the Marquis of Charlton who had so actively interfered in preventing the execution of Markham.

That was his secret.

It was one she had little doubt he would himself proclaim to the queen, but she felt that no one else had a right to do so.

Queen Caroline, however, was pertinacious in her questioning, and Lucy Kerr's only resource was to say that the Marquis of Charlton, if sent for, would no doubt be able to tell her Majesty all she wished to know.

"Then Mr. Osborn shall go for him at once."

The page was duly despatched for the marquis, and during the short interval Agnes looked imploringly at Lucy, as though asking her what she ought to do.

Lucy knew perfectly well how fond the queen was of mystery and anything savouring of the dramatic or the romantic, so she suggested a course which she knew would be very germane to the royal mind.

"Your Majesty would like to hear," she said, "what the marquis has to say, without probably his being aware of the presence of other persons, and if we go into the oratory, the door of which is masked by that Japanese screen—"

The queen did not wait to hear Lucy Kerr conclude, for the proposition was exactly of the kind that suited her.

"Certainly," she cried. "You are quite right. Go into the oratory, all of you, and I will question the marquis. Dear me, it is as good as a play, and a great deal better, too. Go at once, all of you. I can hear Mr. Osborn."

The time young girls had only time to disappear from the queen's cabinet before the page respectfully announced—

"Colonel the Marquis of Charlton, in obedience to your Majesty's commands."

The marquis bowed low. The page quietly retreated and closed the door noiselessly.

"Marquis, we have sent for you because we want to know all about everything, and we are told that you know."

The Marquis of Charlton looked a little startled at such a comprehensive knowledge being attributed to him.

"I am afraid your Majesty has been misinformed."

"Oh! no, marquis, not at all."

The marquis bowed again.

"If your Majesty will kindly say upon what subject your Majesty's inquiries proceed, I shall be most happy to afford any information within my ability."

"Well, then, marquis, who was it that was to have been shot to-night in the Colour Court? And why was he not shot? And who is the young girl who is so fond of him? and is he equally fond of her? and will it be a match? and where is the king? and what else do you know about it?"

"The officer's name, your Majesty, is Captain Markham, of the Guards, he was to have been shot, but—but—"

"Well?"

"The bullets were omitted."

"And where is he now?"

"In my private apartments, your Majesty."

There was a slight movement in the oratory.

"Oh! that's nothing," cried the queen. "I dare say it is Fido fidgeting with his collar. Well, marquis, who is the young girl who I am told would have died with him and for him, as the case might be?"

"I do not know, your Majesty."

"Why, nobody knows her. And we have quite for gotten to ask herself who she is."

"Then your Majesty has seen her?"

"To be sure."

"Oh! your Majesty, it would be such a delight, such a joy, to restore her again to that Captain Markham, whom she must love so sincerely that if it can be quickly brought about—"

"To be sure," interrupted the queen. "Send for him here. Go and fetch him, as you have him."

There was another movement in the oratory.

The marquis looked a little curious. "It's nothing," said the queen. "You go for Captain Markham, and bring him here, marquis."

"I shall obey your Majesty, but every one connected with this affair (always excepting your Majesty, whose high position properly screens you from all peril) stands upon a precipice, and in most imminent danger. His Majesty the king was intent upon the death of this Captain Markham."

"You will leave all that to us, marquis. We know what we know, and we are well aware that his Majesty the king might be as intent upon the preservation of one person as he might be upon the destruction of another."

The marquis understood the allusion of the queen well enough, but he was entirely at a loss to apply it under the circumstances.

"Yes," added the queen, as she took up a fan, and used it rather violently. "Yes, marquis, there are some people who are in the way, and some people who are not. We know all about it."

The marquis bowed, for although he knew nothing about it, he did not think it became him to enter into a contention on the subject.

"I will proceed," he said, " to obey your Majesty's commands, by bringing Captain Markham to your presence, from whence, I hope, he will pass out of St. James's Palace to greater safety than I fear he can ever feel within it."

"Go, marquis, go, and bring him here. If there is any trouble who will send for Sir Robert. He knows everything. Yes, we will send for Sir Robert Walpole, whom we call our minister and counsellor."

The marquis bowed, and retired.

"Be quiet, girls, where you are," said the queen.

"You must let us manage this affair in our own way. Just be quiet where you are."

The Marquis of Charlton was only absent about six minutes, although during that time he had rather startled Markham by the information that he was to have a private audience with the queen.

"There is infinite danger," was Markham's reply. "The queen's power only extends to remonstrances as tears."

"I cannot help it, Markham. Indeed, I cannot help it. But perhaps, after all, it is for the boat; for you will be able to leave the palace now with the connivance of one who can smooth the path for you. The queen can easily order you to be let out by one of your own pages."

"And Bertha?"

"Well, I think I can tell you something of her."

"What, marquis? Oh! what?"

"Nay, there is nothing to apprehend but I fancy she is in the queen's oratory, adjoining the private cabinet. I don't like you to go to this interview with out that knowledge, and I have no doubt that her Majesty's intention is that you may escape together."

"Heaven be praised!"

"Hush! We are there."

"Shall I announce you, gentlemen?" asked Mr. Osborn the page.

"If you please, Mr. Osborn."

The page duly performed his office, and Captain Markham, with the Marquis of Charlton, found himself in the presence of Queen Caroline of England.

"So you are Captain Markham of his Majesty's Guards?"

"I have—"

Markham was going to say that he had the honour, but he stopped himself in time, and substituted the plain answer of, "Yes, your Majesty."

"You are fortunate, sir, in having found a friend who has saved you from a shameful and ignominious death."

"I am fortunate in having found a friend, your Majesty; but the shame and ignominy would have belonged to another."

p. 212

"Well said," cried the queen. "We agree with you, Captain Markham."

Markham bowed.

"And to show that we agree with you, what can we do for your benefit? Ask us for anything in our power, and we will freely do it, for we believe that we have the misfortune to know your story."

These words were quite enigmatical to Markham.

The queen might possibly know his story, but how it could be a misfortune to her to do so he could not comprehend.

The interpretation he had put upon the presence of Bertha at the palace, and the reason she had given herself for the king's violent wish to destroy him (Markham) never occurred to him for a moment.

"Yes," added the queen, "we know all about it, except who is the young lady in question—we mean the young lady who would so willingly have died with you in the Colour Court."

"Her name is Bertha."

"A fair name enough. It comes from my own father land. Is she German?"

"By extraction, I believe so."

"We love and admire her nonetheless, but it is not our love and admiration, Captain Markham, that is in question. It is yours—yours only; and what do you say of the young heart that you have won, and regards you as such an idol that even the love of life itself sinks into insignificance before the dread of parting from you?"

"I can answer, your Majesty, I think, that we always love the thing that we have protected, and it was my happy lot, under circumstances of some peril and some difficulty, to cast my protecting arm around this young girl. I loved her then as I might love a younger sister, or some fair creature who by some special grace of Providence had been entrusted to me to honour and to protect. That that love has grown into a warmer feeling I here avow; and sole possessor of my heart, sole arbitress of all the happiness that can ever in this somewhat sad and weary world be mine, is now that young creature, who, with a fairer sense than I could boast of, drew for me the subtle distinction between love and affection while one was only in its germ, and the other in all its beauty."

"You do love her?"

"Oh! madam, I have said it."

"But she is so young."

"A fault which time will mend. Even as brother and sister, trusting and trusted, even as she has trusted to me, we may yet pass some happy happy years, until I welcome her as the wife who shall be the charm of all life to come."

"Captain Markham," said the queen, "we like you very much, and fully believe and admire every word that you utter. It is something in these days to find a gentleman at once gentle, candid, brave, and noble. Captain Markham, when you see this young creature again you will give her this from the queen."

It was a necklace of costly pearls which the queen handed to Markham.

"I humbly thank your Majesty, and have to prefer but one request, which is that we—I say 'we' because I include Bertha with myself—that we be permitted to leave St. James's, the very air of which is full of danger to us."

"I verily believe it," replied the queen, "and although I am a queen, my power is but weak against the storms of evil passions. You shall go, sir, and take with you her who I hope will love you as truly and sincerely as—well, we will say, as you deserve. And so, being a queen, we will be something of an enchantress, and waving our fan, for want of wand or our sceptre, we will cry, 'Bertha, appear, appear!'"

"Here! Markham! here!"

Another moment she was on his breast, her arms about him, her kisses on his cheeks.

There was no earth, no conventionality there. Bertha loved him, and in the face of all the world she would have held him to her heart.

The queen was deeply affected.

"It is vain," she said. "It is in vain. I cannot even flatter myself that I have the power to protect you. They call me a queen, but I am only a woman—a poor weak woman. I lay down my state and dignity before the first breath of natural feeling, and I tell you all that I tremble—tremble for you. You must fly—fly at once. They call me queen, but I am nothing —nothing."

Queen Caroline burst into tears, and sobbed bitterly. "Oh! your Majesty," said Markham, "to us you shall be a queen, and we shall be ever the grateful subjects that will think of you as what you should be."

"Go. Go at once. Mr. Osborn! Mr. Osborn! Where is Mr. Osborn?"

"Here, your Majesty."

"Mr. Osborn, the back stairs are clear?"

"Yes, your Majesty."

"These are friends—dear friends of mine."

"One moment, your Majesty," said the Marquis of Charlton. "There have been mixed up in this affair—mixed up with it on the side of truth, of justice, and humanity—two other persons, for whom I would solicit your Majesty's most gracious consideration and protection."

"Two others, marquis?"

"Yes—Lady Lucy Kerr, for one—"

"Oh, yes, yes."

"And Agnes—I moan—that is, Lady Agnes Bellair, for the other."

The queen darted a rapid glance at the Marquis of Charlton. No ear was finer than hers in catching the lightest indications of any of that confusion of tone or manner which betrays a half-concealed affection.

"So, so, marquis! Miss Agnes Bellair, then, seems specially to be your care and consideration."

"It needs not, your Majesty, that I should adopt the paltry subterfuge of affecting carelessness and indifference, when every pulsation of my heart gives the contradiction to those words. Loving well, truly, and honestly, and with all my heart, I avow to your Majesty that Agnes Bellair is the object, and has ever been the object, of my dearest hopes and wishes."

"I am delighted to hear it, marquis."

The queen forgot her grief and her dignity again, in the pleasant prospect of another match. "I am quite delighted to hear it, marquis. She is a good girl in every way, and—and—"

"Your Majesty's approbation—"

"Stop! Stop! It so happens, marquis, that we are able to perform another feat, and although there are many bad and evil things that we cannot bid depart from this our court of St. James's, there are some fair and good things that will answer to our call. Agnes, come forth!"

"I am here, your Majesty."

"Agnes!" exclaimed the marquis.

She turned her face towards him, and held out her hand. An exclamation of joy burst from his lips.

"You shall not ask me to be yours, marquis, but I will offer myself for the acceptance of a heart which I now know how to appreciate. Believe, Charlton, that I was blind and benighted, and could not see my way. There is now sunshine on my path, and it is plain and beautiful."

"Good gracious!" cried the queen. "Is there nobody for Lucy Kerr?"

"No your Majesty," said Lucy. "She is quite content to remain as she is, and she will try to find abundant happiness in the contemplation of that of others."

"Yes, yes, that's all very well; but we must find somebody. Dear me! We cannot think of anybody just now. Only think of three matches all at once nearly; for yours, Lucy, must come in time."

Lucy shook her head and smiled faintly, but she knew it was of no use contradicting the queen on such a point as that.

"Dear Bertha," whispered Markham, "all is well now."

"With you, ever, ever well."

"We will leave England."

"For ever, and I will show you the old home which I have spoken to you of as that of my childhood, unless I am a child still, and you will call me one."

He pressed her hand fondly.

The palace clock struck ten.

"It is late," cried the queen. "It is late. Go now, at once. Lucy, Lucy, where is my jewel box? Perhaps you are not rich, any of you. Here, Captain Markham, here is wherewithal to deck your pretty young bride with some years hence."

"We have more than enough, your Majesty."

"Never mind. It is ungracious to refuse a royal gift; and as for you, marquis, we will think of some thing for Agnes at further leisure."

Bertha knelt and kissed the queen's hand, but the good-tempered Caroline raised her up and saluted her cheek.

"There now, my dear, go. Go at once. I am rather surprised at it all, for you are not in his style; but go at once."

"I gratefully and humbly take my leave of your Majesty."

"And I, too," said Markham, "with such a recollection of great kindness that it will never—"

No doubt Markham would have concluded his little speech handsomely enough, but Mr. Osborn, the queen's page, suddenly landed in the room as though he had been discharged from a cannon, and in a voice that struck dismay into every one present he almost shouted—

"His Majesty the king! Half way up the back stairs! His Majesty the king!"

(To be continued in our next.)