Created by Andrew Mobbs on Sat, 04/29/2023 - 20:45

Description:

In On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums, Barbara Black maintains that in the aftermath of Edward FitzGerald’s 1859 translation of Omar Khayyám’s Rubáiyát, Great Britain reduced the significance of Khayyám’s poetry—and the Persian history and culture to which it connects—to being “categorically Oriental” (61). Black argues that western consumerism culture is a driving force behind this phenomenon, as it promotes the notion of collecting (i.e., owning) as a type of conquest. In the case of FitzGerald’s translation of Rubáiyát, Black claims that the British metonymized the original text into a “gem” labeled “pretty, crafted, possessable” (60–61). Consequently, this practice of giving and receiving gift book versions of Khayyám’s Rubáiyát led to its mass appropriation and objectification in Victorian England and beyond.

Of the gift books, Black says, “Elaborately designed gilt covers (sometimes encrusted with stones and protected by miniature locks, both simulated and real) and ornamental title pages indicate the poem’s status as a treasure book…a compelling curiosity” (60). Naturally, her assertion begs the question of whether this 1920 Ronald Balfour-illustrated copy of the text (i.e., Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam) can be classified as such. With limited archival context, it is impossible to know for certain if this particular copy was given and consumed in this manner, especially because it lacks any inscriptions or indications that it was intended as a collectible (i.e., besides the fact that it is part of the Oregon State University Special Collections and Archives). However, based on three specific elements of Balfour’s illustrations, it can be speculated that those involved with the creation and consumption of this book held Khayyám and his Persia at an exoticized distance.

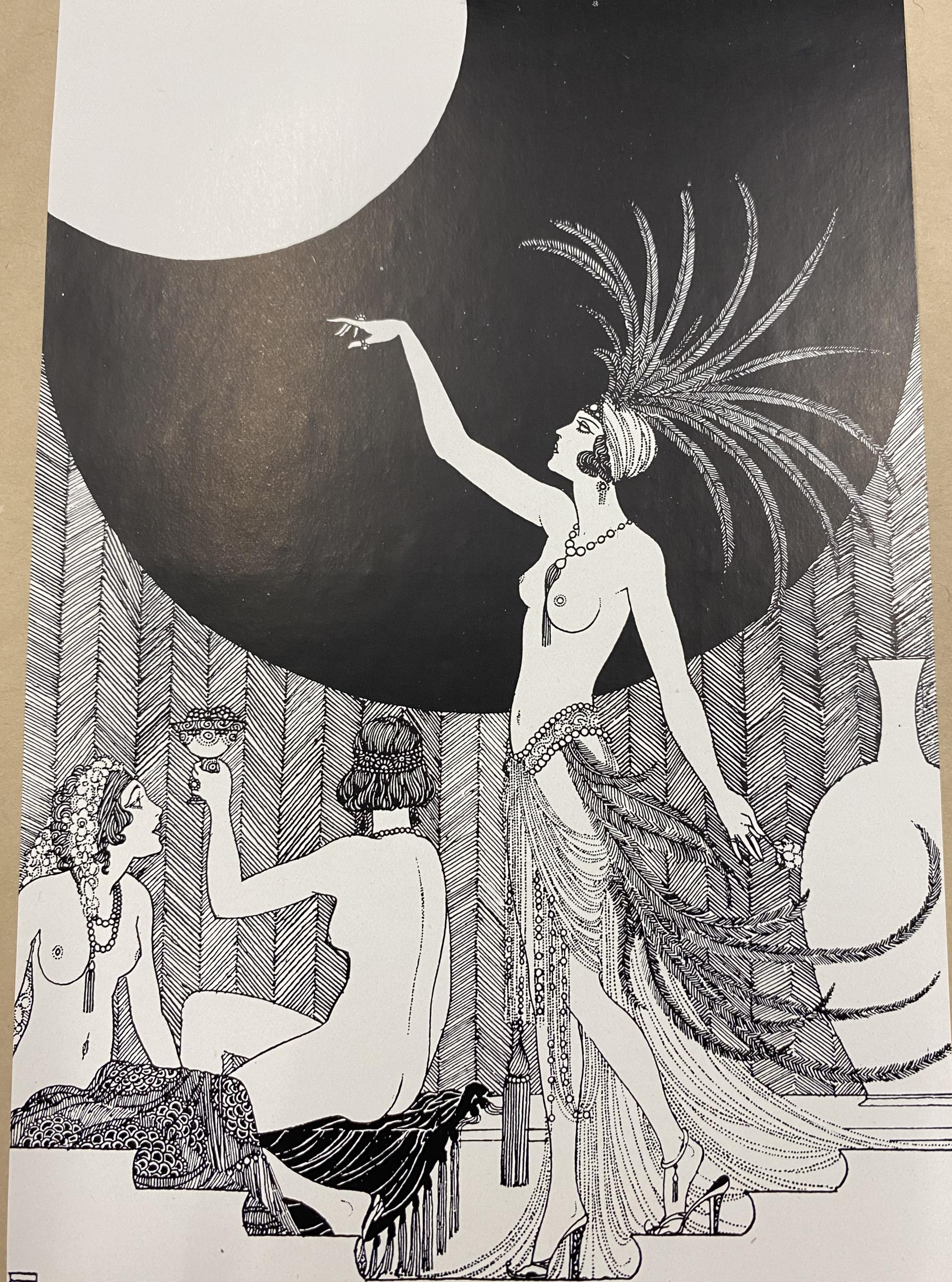

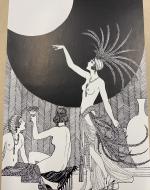

First, in terms of clothing, Balfour’s illustrated characters in this text are either nude women (See Image 1) or women and men clad in what is likely fancified royal attire (See Image 2). Virtually none of these illustrations depict people wearing what would probably be considered normal, authentic clothing within this period of Persian history. With their emphasis on nudity, Balfour’s erotic portrayals could reflect an eastern cultural exotification on the part of Great Britain and western cultures. Common “Oriental” thematic stereotypes, such as feminine meekness and fetishized sensuality, abound in his illustrations (See Image 3). In fact, on several pages, his illustrations do not appear to match the quatrains of Khayyám’s poem with which they are paired in the book (e.g., a nude woman paired with lines mentioning nothing of the sort).

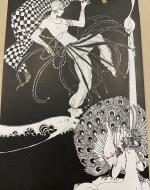

Next, Balfour’s illustrations feature a large amount of peacock imagery (See Image 4). The peacock is a monarchial symbol in Persian culture (“Animals in Ancient Persian Culture”), and Balfour has taken advantage of this despite the fact that no peacocks are mentioned in Khayyám’s poem. Rather, Balfour’s peacocks arguably function as an illustrative delicacy, artistically exaggerated for the sake of display rather than substance, which aligns perfectly with the very notion of peacocking. Additionally, because the peacock is a significant symbol in other Asian cultural contexts (e.g., in India, Japan, China, and possibly elsewhere), Balfour’s peacocks in this text could theoretically be construed as part of the umbrella Orientalism of which Black speaks.

Finally, some of Balfour’s illustrations include what look like tiny logographic symbols within the Japanese writing system (See bottom right corner of Image 5). At the time of writing this, it cannot be determined that these symbols represent the Japanese language (i.e., as opposed to Korean or another language, or simply not being a linguistic symbol), yet it can be speculated as such due to the frequently cited stylistic influence of Balfour by Aubrey Beardsley, a late 19th-century British illustrator known for his decadently erotic artwork who was himself influenced by designs in Japanese woodcuts ("Aubrey Beardsley"). For example, in a section of a 1920 issue of The Bookman called "Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám," which does contextualize Balfour's Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam as a gift book, it is written:

There is something of Aubrey Beardsley’s bizarre imagination, fantasy and wonderful

decorative cunning in Mr. Ronald Balfour’s work, more especially in his black and white

drawings. His paintings do not attempt to reproduce the glow and richness of Oriental

colouring, but in a more subdued and dream-hued fashion (with one exception, when the

colour is crudely barbaric) they express very intimately the spirit and atmosphere of the

East (140).

Therefore, it could be argued that Balfour’s illustrations in this text not only appropriate and embellish Persian culture, but also appropriate and conflate other eastern cultures within the aforementioned label of umbrella Orientalism. Likely, depicting accurate, nuanced Asian cultural distinctions within his illustrations was not one of Balfour’s key concerns.

Works Cited

“Animals in Ancient Persian Culture.” The Peries Project, periesproject.english.upenn.edu/

PeriesProject/animals-in-ancient-persian-culture.html#:~:text=Peacock%3A%20The%symbol

%20of%20Persian,by%20thePersians%20in%201739. Accessed 29 April 2023.

“Aubrey Beardsley.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 12 Mar. 2023, britannica.com/biography/Aubrey-

Beardsley. Accessed 29 April 2023.

Balfour, Ronald. Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. London, Chiswick Press, 1920.

Black, Barbara J. On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums. E-book, Charlottesville, University

Press of Virginia, 2000.

“Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám.” The Bookman: Volumes 58-59. Hodder & Stoughton, 1920, p.

140. Google Books. books.google.com/books?id=biE1U7jTRk4C&dq=ronald+balfour+

aubrey+beardsley&source=gbs_navlinks_s.