Created by aman agah on Mon, 05/01/2023 - 22:26

Description:

Barbara J. Black’s description of the popularity of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam translated by Edward FitzGerald and the subsequent popularity via gift books can be summarized as “‘instant exotica’” (64). Directly before providing this quote from George Steiner, Black states that “the Rubáiyát cannot, in short, divest itself of its oriental drag” (Black 64). Drag implies an exaggerated form of dress-up, that the text in its gift book form passed between devoted fans, is in short, an Englishman’s words dressed in an Oriental costume. As an Iranian* who grew up with Khayyam and other poets like Hafez, Rumi, and Saadi, I cannot separate my own experiences of being exoticized and fantasized from the English/Western presentations of Khayyam. We are loved for the things we create, not who we are. Our poems, our rugs, our turquoise, and other products are the very “collecting as a conquest” to which Black refers - whether “exotically [or] erotically charged” (62).

One of the outstanding notes for me, one which I think can be easily overlooked, is the familiarity with which Khayyam is addressed in so many of these texts, and as evidenced in Black’s piece. Referring to him by first name stands out as a point of familiarity with which the so-called devoted fans, interpreters, and translators presume to have with such a highly esteemed Persian scholar, thinker, and artist. This is further emphasized when juxtaposed with references to FitzGerald by surname. Why does this seemingly insignificant point of names stand out? Because I have not once heard an Iranian refer to Khayyam by his first name, and the parallel of honoring FitzGerald by not assuming familiarity is glaring. But what makes this familiarity feel even more worth noting is that it speaks to a lack of understanding Persian cultural norms. Did the supposed knowledge of Persian culture not lead translators like Roe to understanding the various formal titles which could be applied to Khayyam? At the very least, could they not learn forms of endearment within Farsi that would allow for use of first name alongside other titles such as “Agha”/sir or “jaan”/dear? The familiarity can perhaps be interpreted as its own form of endearment, but ultimately feels patronizing. The tone with which Khayyam is referenced provides more clues to how he was seens as less than. Black provides an example when quoting John Hay, who “speaking to the Omar Khayaám Club in 1897, asserted that between the two poets there was ‘no longer any comparison’: ‘Omar sang to a half barbarous province; FitzGerald to the world’” (61). According to the Oxford English Dictionary “barbarous” includes the following meanings in use during this time period, “unpolished, without literary culture; pertaining to an illiterate people”; “uncultured, uncivilized, unpolished; rude, rough, wild, savage”; “savage in infliction of cruelty, cruelly harsh”; and “like the speech of barbarians; harsh-sounding, rudely or coarsely noisy”. Province is equally important in this quotation, when thinking of the term “provincial”, which includes the definition “parochial or narrow-minded; lacking in education, culture, or sophistication” also in use at the time of Hay’s remarks. There is an almost laughable hypocrisy in referring to Persians as both barbarous and provincial while also celebrating a Persian through gift books and clubs. Perhaps these gift books and clubs would be better named after FitzGerald, if that is in fact who is being celebrated, and given that the translation is more an interpretation and reworking for his particular audience.

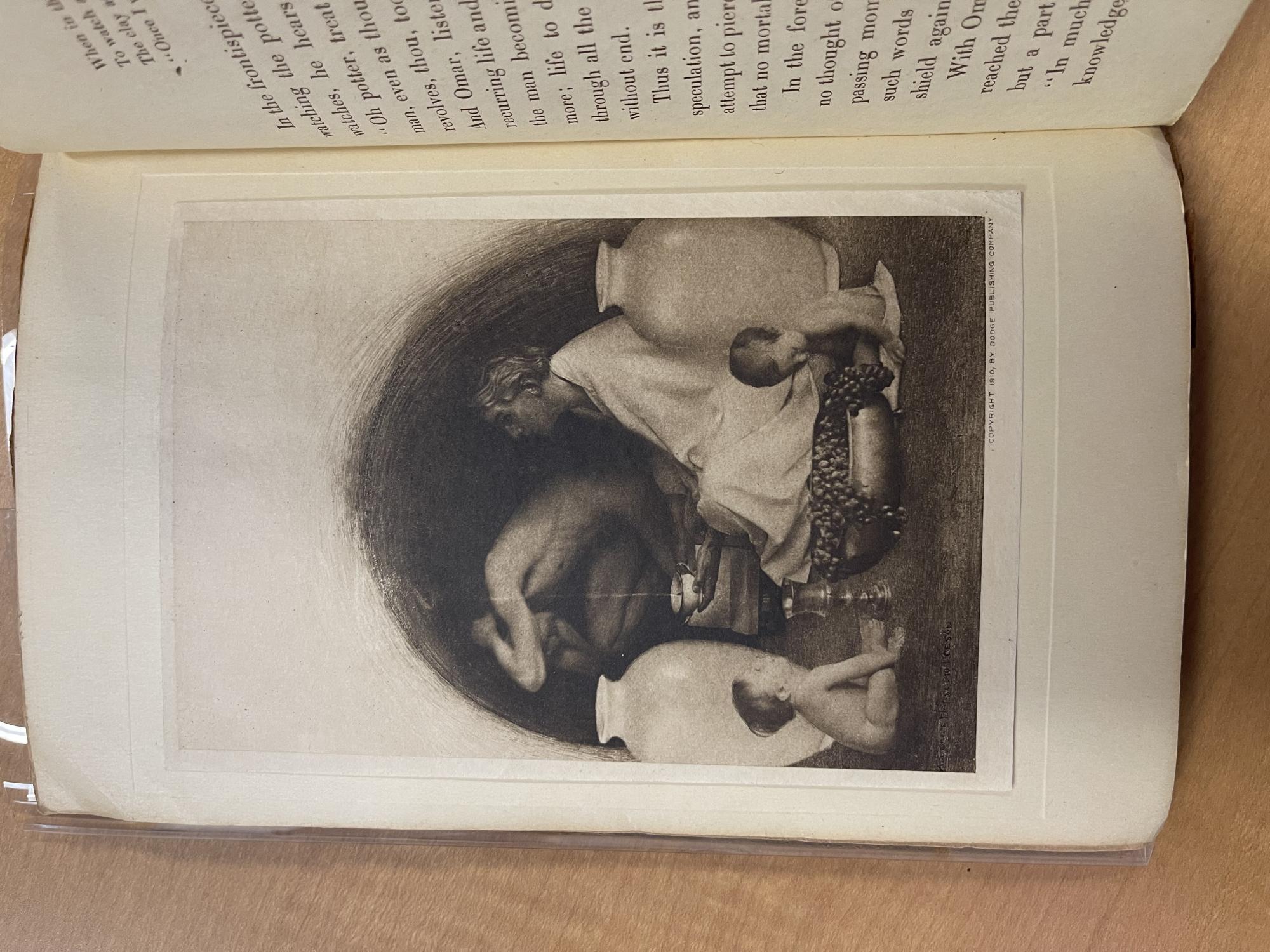

One of the distinctions of George Roe’s translation, Rubá’iyat of Omar Khayyam: A New Metrical Version Rendered into English From Various Persian Sources, is the overarching scholarly tone of the text. At first glance, it appears like many of the other gift books - gold lettering on a rich green cover made of suede (Image 1), and dark green silk paper inside front and back covers. And there is the inclusion of a photograph by Adelaide Hanscom Leeson from her photo collection devoted to the poem, along with a description of some aspects of the photo (Image 2, Image 3). These elements all indicate a gift book. And yet, Roe’s translation diverges in some ways from the more obvious Oriental drag of other Khayyam gift books. Hanscom Leeson’s photo provides a point of divergence in the very front of the text. The same Oriental drag referenced by Black is not present - the people in her photo are not dressed in costumes depicting a white Western view of Persia or the Orient. Though, the photo also depicts a white-washed presentation of the poem, in that the people photographed appear to be white depicting a scene from a poem presumably set in Persia, and featuring Persian people. Additionally, none of the decor are any of the ceramics, or the goblet are distinctly Persian. The messy, or complicated take away for me, in analyzing Hanscom Leeson’s photograph is that while it depicts non-Persians in a Persian world (i.e. white-washed), she also seems to have had enough sense to not dress up her models in offensive costumes. Roe’s introduction further supports this divergence, as he discusses his attempt to not simply produce his own interpretation of, or homage to, Khayyam’s work, rather translate the Farsi with emphasis upon the original intended meaning, and only making changes where seemingly necessary. Within the pages of the poem Roe includes copious footnotes, including Farsi text, and context for choices made in translation. And yet, Black’s arguments can certainly still apply to Roe’s work. He was a member of Omar Khayyam Club of America, and his translation is dedicated to specific members of the group. He presumes the same level of familiarity with Khayyam in referring to him by his first name. And perhaps, just perhaps, this text is a place for Roe to prove his knowledge of Farsi and what he at least assumes to be Persian culture. In that attempt to show, not share, knowledge, one could argue that Roe is simply taking part in one of those club meetings or “Persian dinners and display[ing] [his] collected Eastern exotica” (Black 60).

An argument can be made that Roe is deeply in awe of Persian culture, language, and art, given his attention to detail in translation, and his extensive study of other translations, as evidenced in his introduction. However, Roe also clearly lacks an understanding of Khayyam’s connection to Islam and Islamic mysticism, most obvious in his statement that “the Aryan instincts of the more intelligent Persians led them to discard the Semitic materialism of Muhammad [swt] for a belief more profound and spiritual than their Arab conquerors could teach or appreciate” (Image 4) (13). Roe’s attempt to speak highly of Persians via Islamophobia and anti-Arab language only speaks to his own ignorance about Khayyam and Khayyam’s poem as, in part, a conversation between the poet and the Qu’ran. Roe’s Islamophobia is further expanded upon by claiming that the Sufi and Persian mysticism can be connected back to Plato, so ultimately, Roe argues that it is the Western world which is responsible for the philosophical poetry of Khayyam.

*I do my best to use Iranian when referencing myself and in the context of the present, and Persian when discussing the time of Khayyam and the gift books. While there are folks who still use Persian to describe themselves, my personal preference is for Iranian.

Works Cited

“barbarous”. OED Online, Oxford University Press, March 2023. www.oed.com/view/Entry/15397. Accessed 24 April 2023.

Black, Barbara J. On Exhibit: Victorians and their Museums. University Press of Virginia, 2000.

Omar Khayyam and George Roe. Rubái’iyát of Omar Khayyám.Rubá’iyat of Omar Khayyam: A New Metrical Version Rendered into English From Various Persian Sources. Dodge Publishing Company, 1910.

“provincial”. OED Online, Oxford University Press, March 2023. www.oed.com/view/Entry/153461. Accessed 24 April 2023.