Created by Ginnie Sandoval on Wed, 05/03/2023 - 17:43

Description:

In her book, On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums, Barbara Black calls FitzGerald’s translation of Omar Khayyám’s Rubáiyát a “tamed familiarized object” made to feel exotic without feeling foreign. She tells of Edward FitzGerald being a collector; one who travels within the confines of his own home, living vicariously through the items he collects, or through the museum of his making – “To FitzGerald, the otherworld was safely intriguing when it lay on the other side of one’s room” (51).

FitzGerald already harbored a growing passion for all things Oriental when he began to translate Khayyám’s Rubáiyát. He believed that the collection of Oriental items created a joyful presence. It wasn’t necessarily one item that created it, but rather the collection as a whole. When it came to translating Eastern text, Black points out that although he claimed to be concerned with authenticity, he was more focused on “packaging the Orient for all the world’s homebodies” and consequently, he purposely altered the Rubáiyát to suit both his and English standards. A notable example of his alterations is the attention he paid to form rather than to actual content, opting to create a narrative and connecting pieces within the stanzas. By doing so, he ignored the Persian traditions surrounding that which was the ruba’i. However, FitzGerald’s alterations did end up paying off because the Rubáiyát eventually became a very sought-after item.

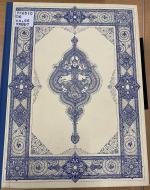

When the Rubáiyát came into popularity, it became known as a “Treasure Book”. It drew people in with its golden leaf/golden painted covers, decorative title pages, and dedication page. Because of these characteristics, the Rubáiyát soon became a popular gift book. Here in came Black’s argument that the Rubáiyát’s “value becomes inseparable from its pretty, crafted, possessable diminutiveness. Khayyám’s verse remains entrenched in the categorically Oriental, in the land of seers and Eastern serenity” (61). She argues that the poem was both objectified and appropriated when its otherness was de-emphasized. Black implies this is proven by the poem’s reception history and how it indicates “that possessing the text was as important as reading it, if not more so” resulting in “the thrill involved in possession is consistent with the rhetoric of conquest that characterized this text’s existence in the West” (61).

Regarding this particular book, as a First Edition Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, published in 1946, this version of the Rubáiyát exemplifies Barbara Black’s reasoning that the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám has continuously been appropriated since FitzGerald’s translation of it in a number of ways. When it comes to its exemplification, although this version was published nearly one hundred years later, there are hardly any changes compared to Black's descriptions. We see that many of the stanzas are accompanied by striking images gilded in gold. Because these images typically refer to one specific stanza, this points to the alterations FitzGerald made to suit English standard, venturing away from traditional Persian Ruba’i and supporting Black’s argument of appropriation. FitzGerald valued form above content and we can clearly see this in the pages in this Rubiyáát. Looking at the first 7 stanzas of the poem (figures 5 and 6), there is a narrative that the reader can easily follow with each stanza connecting to the last. Black meantions that in Persian culture, the Ruba'i can sometime be seen as more of a person jotting down their thoughts. As one can imagine, this might not have any flow or consistency, and that is where we see, from this particular version, the appropriation of Persian culture to fit European standards.

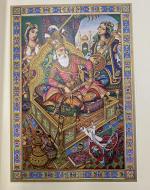

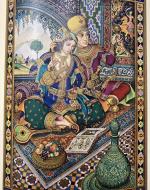

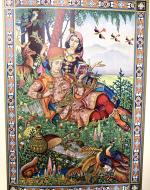

Another consideration that supports Black’s argument is her observation that “the most frequent image critics use to discuss the Rubáiyát – the gem, jewel, pearl, or ring of gold – encapsulates the poem’s problematic status in a museum culture” (60). The problematic status of museum culture that Black speaks of is the fantasy of the Oriental that Europeans held and how instead of an interest in authenticity, they were satisfied to accept the poem as an object of their English idealisms. Accepting FitzGerald's translation of the Rubáiyát at face value meant having a piece of the Oriental - or their farce idea of the Oriental. Again something exotic yet not foreign, or as Black puts it, the excitement was in the possession of the poem rather than the poem itself. Hence becoming a popular gift book. Along with the gilded gold, this first edition of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám hosts a number of images that display gems, jewels, pearl, and golden rings (figures 1-4). Before digging deeper into these images, it's important to point out that Black also mentions how, when being popularized as a gift book, the poem/book was miniaturized both physically (to better suit it as a gift/treasure) and metaphorically, ultimately taking even more away from the true authenticity of it.

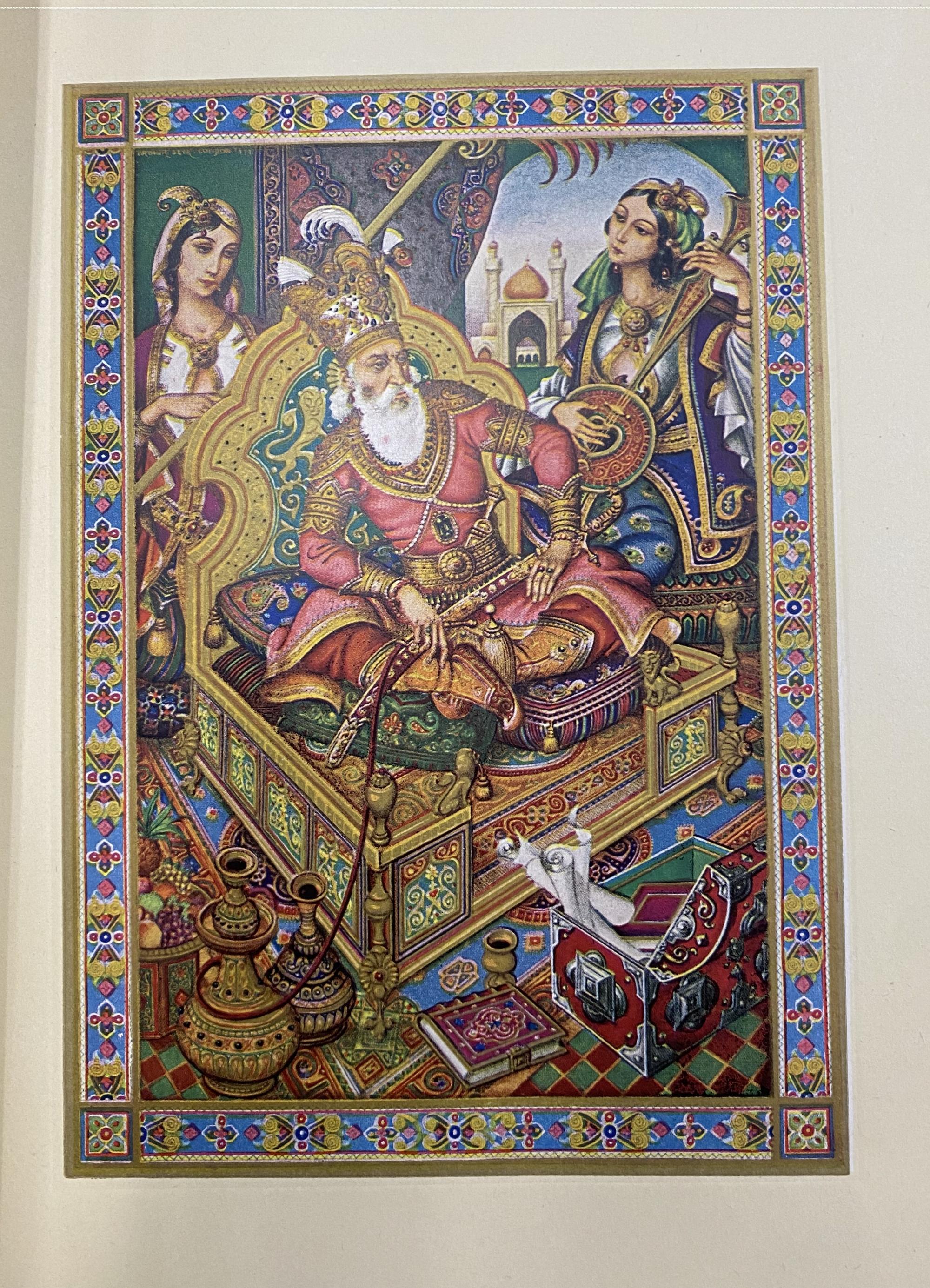

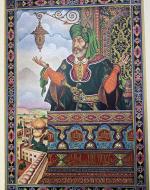

Each of the four images displayed plays a part in the appropriation of the Rubáiyát because of how it coincides with Black's statement regarding the way it became popularized as a gift book and how it drew its audience in. Figure 1, shows a gentleman relaxing on a jewel encrusted bed and dressed in jewel encrusted clothing. Both his attire and his surroundings are exotic and showcase the fantasized idea of Persian culture. The man is surrounded by treasures and numerous pleasures - smoking a hookah, being fanned, and having music played for him. This is clearly referencing the pleasures of life spoken within the stanzas, a common theme seen in the other images. These are the images Europeans wanted to see to satisfy their fascination.

Interestingly, in many of this version's Rubáiyát, there can be seen a small book in many of the images (see figures 1 , 2 , 3), which definitely seems to encourage the Rubáiyát to be viewed as both a treasure book and gift book. Other similarities in the images are again, pleasures, treasures, and jewels. Most importantly though, is the rich color and designs in each of the images. Arthur Syzk, the illustrator, drew these images in color and gold. Not only that, but they were engraved into the book, giving them a popping out effect, and making them even more striking. As Black pointed out, as a “Treasure Book”, the Rubáiyát drew people in with its golden leaf/golden painted covers and decorative title pages, which ultimately made it a very popular gift book. Nowhere can this be seen more that within Syzk's gilded-golden, treasure filled, images.

Black, Barbara J.. On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums. United Kingdom, University Press of Virginia, 2000.

Khayyám Omar. The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám Rendered in English Verse by Edward FitzGerald. The Heritage Press, New York. Copyright 1946. Illustrations by Arthur Szyk. Sun Engraving Company. Franfare Press, London.

Copyright:

Associated Place(s)

Part of Group:

Featured in Exhibit:

Artist:

- Arthur Szyk