Created by Sierra Sherland on Thu, 05/25/2023 - 20:48

Description:

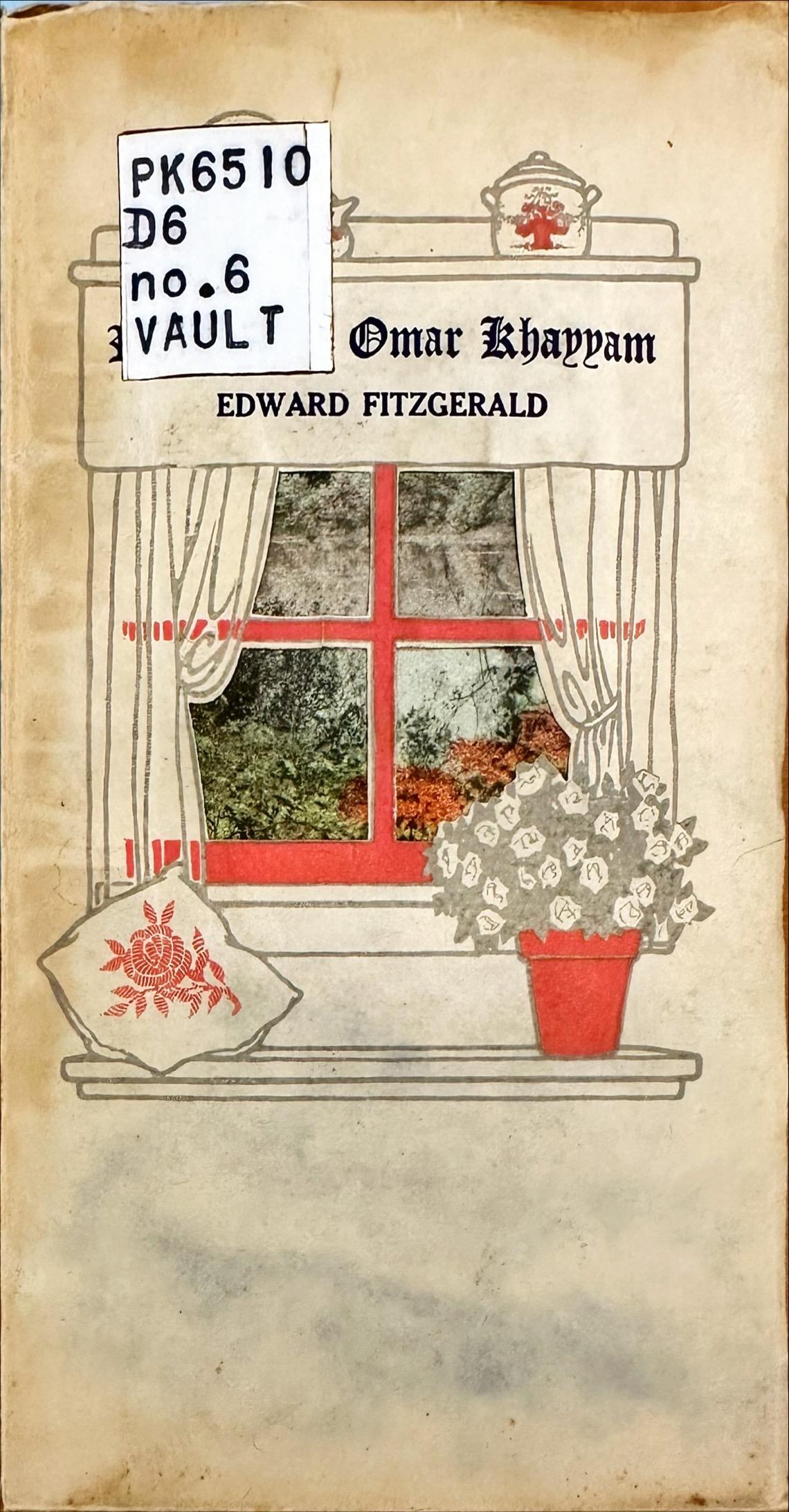

In R. F. Fenno’s giftbook edition of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam, the visual motifs are sparse, essentially inconsequential to the text or plot of the poem. This is unlike many other gift book editions of the Rubaiyat, where the packaging and visual components serve as the primary point of value of the text. Barbara Black argues that the gift book culture that formed around the Rubáiyát and its emphasis on the ornamental is an example of Orientalism, alongside elements of the translation done by Edward Fitzgerald. Rather, the visuals in this edition appear to be standard ornaments that the publisher owned with no particular relation to the Rubáiyát. The entire edition seems to be haphazardly thrown together. However, perhaps accidently, the depictions of domesticity relate to the Rubáiyát’s theme of finding contentment in the present rather than a pursuit of higher understanding.

STANZA XXXIX

How long, how long, in infinite Pursuit

Of This and That endeavor and dispute?

Better be merry with the fruitful Grape

Than sadden after none, or bitter Fruit.

Stanza XXXIX in the Rubáiyát in particular highlights the text’s main argument, that one should be happy with the present and what they have rather than worry about existential questions. The stanza begins with “How long, how long, in infinite Pursuit” (35). This stanza follows two previous stanzas that discuss large, cosmic concepts, such as the “Well of Life” and “Annihilation’s Waste”. The repetition of “how long” serves to emphasize the speaker’s view that worrying about these grand concepts is a waste of time. The form of the entire poem is comprised of four lines in an iambic pentameter. Repetition like this then is an incredibly inefficient use of space, which serves to highlight the speaker’s argument. This is also shown in the second part of the line, “in infinite Pursuit,” there is no end to the pursuit of answering these questions. The second line follows with “Of This and That endeavor and dispute?” Similarly, the use of the phrase “this and that” mirrors the repetition of “how long” in the previous line. The endeavors the speaker is referencing are not important enough to be given proper names, and instead are “this and that,” which despite being different words convey the same unspecific object.

The second two lines of the stanza build on the previous theme and solidify the speaker's argument and give the conclusion. “Better be merry with the fruitful Grape, Than sadden after none, or bitter Fruit.” The speaker here is saying it is better to be happy or grateful for what you have, the grape, instead of being sad with what you do not have. The use of grapes is an interesting allusion, because while grapes are small fruits they have often been symbols of luxury, such as the image of someone reclining eating from a bunch of grapes. In other words, you can find the luxury in life even from something small. Overall, this stanza serves to reinforce the theme of living in the moment and find joy and excess in the everyday.

The cover of this edition (Image 1) of the Rubáiyát features a window with a bench, decorated with cozy pillows and curtains, with quaint looking pots shelved above. The window faces out into an abstract nowhere, with no discernable imagery in it. The imagery is particularly puzzling because of how Orientalist Rubáiyát editions tend to be, but this home scene instead appears very western. While there is a dissonance between the imagery of the cover and the origin of the poem, the portrayal of a simple home scene does align with the theming of the poem, especially the theme of being content with the present and the everyday.