Created by Jerome McGann on Tue, 12/17/2019 - 18:36

Description:

A variant of this description was originally published at The Rossetti Archive.

Scholarly Commentary

Introduction

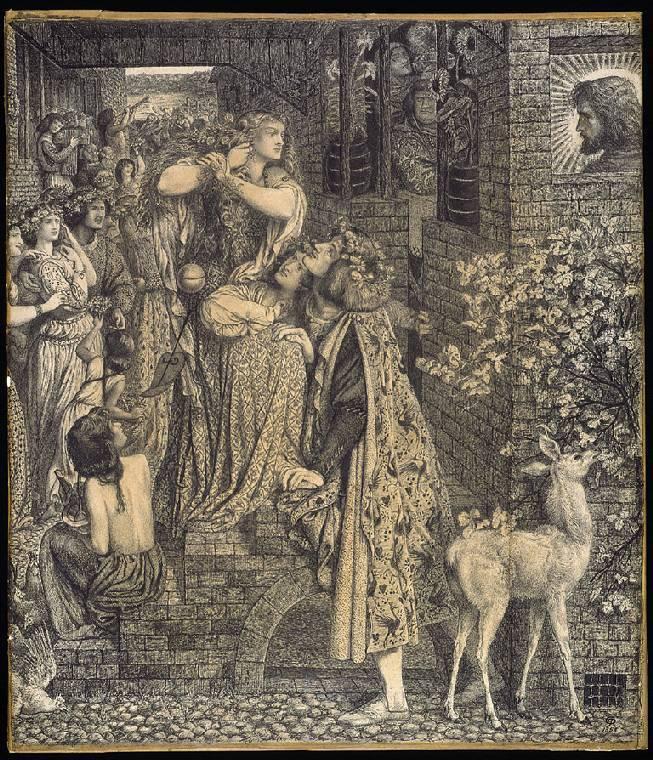

This famous drawing gives an important statement of Dante Gabriel Rossetti's thoughts about the relation of pictorial forms of representation to the expression of ideas. Indeed, the picture amounts to a formal embodiment of its own thinking. Like The Girlhood of Mary Virgin and Ecce Ancilla Domini!, it is a strongly programmatic work.

Rossetti named the central idea of the picture “two houses opposite each other.” The phrase signifies primarily the opposed houses of worldliness and spirituality, here shown competing for the soul of Mary Magdalene. But Rossetti's unusual drawing forces the phrase to signify as well another closely related opposition that concerns the practise of art. For Rossetti, Pre-Raphaelitism manifested an artistic contradiction that he sought to illustrate in this drawing.

His argument appears most dramatically as the aesthetic contradiction represented by the image of Christ. The conceptual (though not the emotional) center of the drawing is this image, which enters the picture as an iconic form. This form represents a key moment of pictorial contradiction. Abutting the right border of the picture, and wholly framed within the window space, the form of Christ will be seen at the level of the picture plane itself. The form occupies a fundamentally ambiguous position, and we are also invited to see the form more realistically, as a head in a window that opens into a room with other figures, or, finally, as an artistic image of a religious icon. In this last view, the image of Christ is placed on the forward plane defined by the exterior wall of Simon's house, as if it were hung there like a picture. In the left and center areas of the drawing, however, Rossetti constructs an illusionistic space in standard perspectival terms. (Those are the terms inviting us to see Christ's head in a window, as part of the drawing's illusion of, and allusion to, “realistic” space.)

The drawing recalls Rossetti's admiration of primitive style and the alternative it offered to perspectivist rationality. Indeed, the latter becomes here the technical exponent of an art committed to “soulless self-reflections of man's skill” (Rossetti qtd. In Bentley 202). In practical terms Rossetti represents worldliness as space organized according to lines of perspective. This is the recessive area of street, procession, high road, and the distant river.

As in nearly all of Rossetti's work, the drawing is structured around different areas, each of which forms a center of attention in its own right. Perspective does not organize these pictorial areas; rather, it becomes itself a kind of figural event, a way of imagining and representing pictorial space. Rossetti makes space function as part of an argument about spiritual and aesthetic values. In the picture, spatial recession locates negative values, whereas the icon of the head of Jesus is a positively charged gravity center. That stylistic opposition grounds the programmatic character of the drawing and argues for a more catholic way of thinking about pictorial space than the Albertian tradition authorized in the academy.

Rossetti's argument using artistic form becomes further elaborated as we notice the other principal aesthetic contradiction in the drawing between the meticulous realism at the level of small details, on one hand, and the symbolic detail that governs the picture at a higher scale of perceptual awareness, on the other. The fawn that “crops the vine” in Rossetti's cunning description brings the differential into sharp focus. The animal locates a moment of ornamental symbolism in the picture, yet its scale and fine draughtsmanship demand more attention than what might be expected for such an accessory. This out-of-scale treatment of the pictorial elements is distinctively Pre-Raphaelite. To realize its significance more clearly, one has only to look at Rossetti's early Poe and Faust drawings, where a more realistic drawing technique defines the separation of nature and supernature (in The Raven: Angel Footfalls, for example).

The sonnet that Rossetti wrote to accompany the picture replicates this opposition in the division between octave and sestet: the former is spoken by the Magdalene's worldly lover, calling her back; the latter by the Magdalene, who longs for Christ. Her desire receives a remarkable form of expression when she speaks of “my Bridegroom's face / That draws me to him” (lines 9-10). Playing on the word “draws,” Rossetti makes an arresting claim for the picture he has executed. The words lie open to various readings, but all assert the spiritual authority of a certain kind of art, and of this picture particularly.

Production History

Dante Gabriel Rossetti contemplated an oil picture on this subject as early as July 1853, and he began executing a drawing (or drawings) at that point. He may have made a sketch even earlier. In 1857 he was working assiduously at this elaborated drawing, which he was intending to finish for the semi-private Russell Street Pre-Raphaelite exhibition in June, but he kept working on the drawing through that year and the next. He seems to have completed this work in 1858 (Fredeman, Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti 1853.41, 1858.16, 1859.11, 1859.15, 1859.42).

Reception

This work has always been considered one of Dante Gabriel Rossetti's greatest pictures. John Ruskin in particular admired it enormously: “magnificent to my mind, in every possible way,” he wrote at the time to Rossetti (William Michael Rossetti 183-4). Its influence was considerable, most notably on Edward Burne-Jones and Charles Ricketts.

Iconographic

Dante Gabriel Rossetti's description of the picture in his letter to Mrs. Clabburn (July 1865) defines the Christological symbology ("Letter to William Houghton Clappburn"). It does not point out that this figurative material also operates at a second-order level, as a quasi-allegorical commentary or programmatic statement of Rossetti's ideas about art.

Pictorial

Alastair Grieve rightly says that “The elaboration of detail is Düreresque and the composition resembles that of Dürer's Nativity in the Small Passion. The bird pattern on the lover's cloak is taken from a plate showing a fourteenth-century North Italian costume in Bonnard's Costumes Historiques (1830 II. no 54)” (Parrott, The Pre-Raphaelites 284).

Rossetti associated the work with his contemporary-life picture Found, which he had conceived and begun around the same time as this work.

Literary

The scene is imaginary and symbolic, though the central event refers to the events narrated in Luke 7:36-50. Several details refer to other biblical passages: The fawn cropping the vine, a eucharistic figure of the soul, comes from Psalms 42:1. Dante Gabriel Rossetti himself said that the detail of the birds sharing “the beggar girl's dinner [gave] a kind of equivalent to Christ's words” in Mark 7:28 (from a July 1865 letter to Mrs. Clapburn) (see Surtees, Paintings 1: 62-65). Here one inevitably recalls as well Matthew 6:26.

Physical Description

Medium: Pen and India ink.

Technique: Pen and India ink, laid down.

Dimensions: 21 1/4 x 18 3/8 in.

Signature: Monogram.

Date on Image: 1858.

Note: Monogram and date in lower right corner.

Production Description

Production Date: 1858.

Exhibition History: 4 Russell Place, Fitzroy Square, Pre-Raphaelite Exhibition, 1857 (no.58); Manchester, 1911 (no.177); Tate, 1923 (no.225); Birmingham, 1947 (no.228); R.A. 1973 (no.115); Yale, 1976 (no.38); Victoria and Albert Museum, 1977-78 (no.121); Cambridge, 1979 (no.174); Cambridge, 1980 (no.4); Tate, 1984 (no.223); Torre de'Passeri (Pescara) 1984.

Patron: Thomas Plint.

Date Commissioned: 1858.

Original Cost: Perhaps 50 guineas.

Model: Fanny Cornforth, Ruth Herbert, and Annie Miller have all been suggested by scholars as the model for Mary Magdalene.

Note: Alastair Grieve says that the model was Ruth Herbert (Parrott, The Pre-Raphaelites 284). Doughty surveys the ambiguous evidence on the issue (A Victorian Romantic 682-83).

Provenance

Current Location: Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

Catalog Number: 2151.

Purchase Price: Bequest.

Archival History: First owned by Thomas Plint, the drawing disappeared after his death in 1860; Charles Ricketts found it by accident in a store in the Brompton Road in May 1898 (see Marillier 97, and the 27 May 1898 diary entry in Shannon's diary, British Library Add MS 58110); Shannon and Ricketts bought it for £150. The diary entry shows—from a fragment of a letter that was found with the drawing—that Dante Gabriel Rossetti had it photographed himself. It went as a gift to the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1937 (Ricketts and Shannon bequest).

Works Cited

Bentley, David M.R. “Rossetti’s Pre-Raphaelite Manifesto: The ‘Old and New Art’ Sonnets.” English Language Notes, vol. 15, no. 3, March 1978, pp. 197-203.

Doughty, Oswald. Dante Gabriel Rossetti: A Victorian Romantic. Yale UP, 1949.

Fredeman, William E. The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. D. S. Brewer, 2002.

Grieve, Alastair. Art of Dante Gabriel Rossetti: Watercolours and Drawings of 1850-55. Real World Publications, 1979.

Marillier, Henry. C. Dante Gabriel Rossetti; An Illustrated Memorial of His Art and Life. Creative Media Partners, 2018.

Parrott, E.O. The Pre-Raphaelites. Tate Gallery, 1984.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. “Dante Gabriel Rossetti Letters to William Houghton Clabburn.” Yale Center for British Art, 1863-65.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. "Letter to Hannah Louisa Clappburn, 6 July 1865." Dante Gabriel Rossetti Letters to William Houghton Clabburn. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund.

Rossetti, William Michael. Ruskin: Rossetti: Preraphaelitism. Dodd, Mead and Company, 1899

Ruskin, John. Pre-Raphaelitism. Knickerbocker Press, New York, 1891.

Surtees, Virginia. The Paintings and Drawings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti: A Catalogue Raisonné. 2 vols. Oxford UP, 1971.

.

Copyright:

Associated Place(s)

Featured in Exhibit:

Artist:

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti