Wood Engraving Technology Dominates the Victorian Illustrated Book

Wood engraving, a form of relief reproduction technology, dominated the mid to late Victorian illustrated book publishing industry. Unlike the traditional woodcut method of image production which involved carving into the side of a wooden plank with a knife (Kooistra), wood engraving technology employed tools such as ‘spitstickers’ and ‘lozenge gravers’ (Royal Academy of Arts) to cut out the white segments of the image and accentuate the raised outlines of the woodblock which were then inked and pressed onto paper. In light of this methodology, the practice was also known as “the art of the white line” (Walker 15).

Though wood engraving can be traced back to eighth-century Japan (Hunsberger), its success in the Victorian illustrated book market is attributable to the European tradespeople who recovered the art. Most notable of these tradespeople is Thomas Beswick (1753-1828), the English engraver and silversmith who reformed the practice for metal and wood (Hunsberger) and is credited with the innovative development of graving out the “whites” of the design (Kooistra). Beswick’s technology gave way for the mass-production of illustrated books, periodicals, and magazines during this period as it efficiently allowed for the wood-engraved image to be set up with letterpress type, it was suitable for multiple usages after a metal mould was cast from the original block, and its process could be mediated by labour and manual technology at the height of industrial capitalism in England (Kooistra). From 1850 to 1880, wood engravings accounted for upwards of 25% of all the illustrations published in illustrated books in Britain (Allingham).

Despite the notion of wood engraving in the mid-century as a “good and stable profession,” (National Museums Scotland) its popularity declined dramatically at the end of the 1800s due to developments in line illustration and photomechanical imaging. Although many engravers were experts at recreating the work of illustrators, they could not compete with the facsimile image produced by photography.

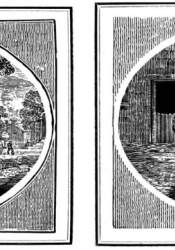

Image: Two plates by Thomas Bewick from The Fables of Aesop (1818): "The Dog in the Manger," "The Cock and the Jewel."

Sources Referenced:

Wood Engraving as an Art and a Trade