Wood Engraving as an Art and a Trade

The 1896 Bodley Head edition of The Were-Wolf used as the copy-text for The COVE edition features six full-page wood engravings created by Clemence Housman after pen-and-ink drawings by Laurence Housman. These images, essentially collaborative in their production, represent the multimodal nature of the text itself. The process of wood engraving, whether industrially on a large scale or in the kind of close artistic partnership of the Housman siblings, involved the work and art of many different people, whose work on such a project was usually invisible in the final project, and remains invisible to this day (Kooistra 2). Clemence, author of The Were-Wolf, was known within her artistic London circles first as a wood engraver, and the work and art of wood engraving comprised a significant portion of her earnings throughout her life. For Clemence, however, wood engraving represented the meeting of her considerable artistic talent and her need for employment—the craft was a passion for her. Though her considerable success as an author should be celebrated and noted, the skill of Clemence’s engravings must be recognized as well. Engravings were designed to erase the work of the engraver, and foreground the work of the illustrator. Ironically, Clemence’s skill as a wood engraver means that her own work was erased in the final image.

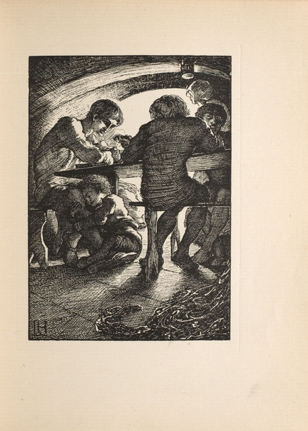

Figure 1. "Rol's Worship." Wood engraving by Clemence Housman after Laurence Housman's design showing her skill.

Figure 1. "Rol's Worship." Wood engraving by Clemence Housman after Laurence Housman's design showing her skill.

The goal of wood engraving was to recreate the artist’s drawing without leaving any marks of the engraving (Kooistra 2). In her article about wood engraving in a pamphlet entitled Occupations for Women, Other than Teaching, Clemence comments on the value of wood engraving as a worthy occupation for an artist; less “showy,” perhaps, than other employments, but still valuable and profitable (Housman 4). Engraving was a prolific trade in the Victorian London publishing industry, with large engraving firms, as well as freelance engravers, flourishing in mid-century. Clemence worked in both venues and encouraged the trade as a fitting trade for women because of its portability, moderate expense for supplies, and the necessary skill of attention to detail (Housman 5). She promoted the trade because of its perceived long-term profitability, ironically not foreseeing she herself would shortly encounter a dramatic decrease in work brought about by the rise of photomechanical engraving processes in the 1890s. Though Clemence began as a freelance wood engraver, employed by Illustrated London News and The Graphic, among other large publications, she was forced to adapt to the changing industry, and like many other engravers, challenged herself to embrace the artistry of the form itself to make her skill profitable once more (Engen 127; vii).

Figure 2. Bewick block. By Gemena. Wikimedia Commons

Figure 2. Bewick block. By Gemena. Wikimedia Commons

Wood engraving was known colloquially as “the art of the white line,” because of the cuts made in a block of wood to create white space in an image and reveal the raised outlines of the form, which collected the black ink (Walker 15). The creation of an inked line in an image requires two parallel cuts made in the wood, which result in a raised line. Wood engravers cut against the grain of wood block, in the end grain of the block of wood, with Turkish boxwood being the most common medium at the time (Sander 15). The practice has roots in eighth-century Japan, and was recovered by European tradespeople, most notably Thomas Bewick, an English silversmith and engraver. Bewick saw engraving as both artistic expression and as a potentially profitable trade, and developed the practice in both metal and wood (Sander 15). The engraver had to think of the wood as the “black space” in a painting, and the process of engraving the white space as illuminating the non-black space on the block (Sander 16). Therefore, the art is in the “grey” of an image, and the space that is not necessarily black or white.

Figure 3. Two wood-engraved blocks bolted together. Dalziel Collection in British Museum. Photo by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra

Figure 3. Two wood-engraved blocks bolted together. Dalziel Collection in British Museum. Photo by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra

In the Victorian period, small-scale engravers worked in their own shops or homes, but many engravers worked for large engraving firms, in which many engravers might work on one image. In these companies specializing in the production of large images, engravers each worked on a certain part of the image, for example, faces, flowers, or landscapes, and then bolted the segments together to create the full image (Sander 18). Therefore each large image was not only the work of one illustrator and one engraver, but possibly of many engravers, each contributing their specialty. These image blocks were then bolted together with text blocks if necessary, and printed on large presses in factories. At its height, the number of wood engravers in Britain numbered four to five thousand practicing, and there were factories making tools for the craft, as well as apprentice schools in which to teach it (Sander 19).

Figure 4. Victorian Wood Engraving Tools in the British Museum. Photo by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra

Figure 4. Victorian Wood Engraving Tools in the British Museum. Photo by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra

Given the widespread practice of this craft, it seems extraordinary that it has been largely forgotten. Clemence’s artistic work as an engraver is largely effaced by the illustrative and literary work of her brothers Laurence and Alfred, which seems to reflect the work of wood engravers in the publishing industry more broadly (Kooistra 2; Engen 127). However, as mentioned previously, the art of wood engraving was to erase the work done by the engraver themselves, and to foreground the work of the illustrator; thus the invisibility was a part of the craft itself. Notably, in the later 20th and 21st century revivals of wood engraving as an art the goal is now to reveal the craft and work itself as its own artistic expression.

The Were-Wolf was Clemence’s first major commission for a book publisher, and signals her transition from the reproductive engraving industry to the Private Press movement, which attempted to preserve the art of wood engraving. In addition to engraving illustrations by Laurence Housman for trade publishers, Clemence Housman engraved for Charles Ashbee’s Essex House Press and James Guthrie’s Pear Tree Press. Her last commission was for F.L. Griggs’s architectural series of Chipping Campden. Clemence Housman, combining her extensive technical skill in the craft, and her respect for wood engraving as something that is valuable in itself, is an essential part of the history of engraving and the development of the craft.

Emily Hunsberger, Ryerson University, 2018.

Citation: Hunsberger, Emily. “Wood Engraving as an Art and a Trade,” Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Emily Hunsberger, et al, COVE Editions, 2018. https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/wood-engraving-art-and-trade

Works Cited

Engen, Rodney K. “Housman, Clemence Annie.” Dictionary of Victorian Wood Engravers. 1985.

—. Preface. Dictionary of Victorian Wood Engravers, by Engen, Chadwyck-Healey, 1985, pp. vii-viii.

[Housman, Clemence]. ‘Wood Engraving.’ Occupations for Women Other Than Teaching. London: Association for Assistant-Mistresses, 1887. 3-5. Pamphlet in Mark Samuels Lasner’s Laurence Housman collection, 62.1, U Delaware Library.

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “Victorian Women Wood Engravers: The Case of Clemence Housman.” PDF. Forthcoming in Women, Periodicals and Print Culture in Britain, 1830s-1900s: The Victorian Period, edited by Alexis Easley, Clare Gill, and Beth Rodgers, Edinburgh UP.

Sander, David M. Wood Engraving: An Adventure in Printmaking. The Viking Press, 1978.

Walker, George A. The Woodcut Artist’s Handbook: Technique and Tools for Relief Printmaking. Firefly Books, 2005.