Blood in The Were-Wolf

The fascination with blood in Victorian gothic narratives is due both to its associations with religious doctrine and its link to the corruption of the individual, as well as its role in traditional lycanthropic folklore and vampire literature. Lycanthropy literature has always linked consumption and blood, associating both with cannibalism and manic or maddened states. Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf challenges this paradigm by contrasting the werewolf White Fell’s compulsion for the consumption of blood with Christian’s redeeming qualities of blood spilled in love and sacrifice.

Housman’s representation of the purity of blood alludes to societal concerns present in the late-Victorian period. In the popular genre of vampire fiction, the disease and corruption of blood through transfusion or consumption expressed the fear of sexuality. Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) is the most well-known and representative novel of this genre. It is only through the murder of the vampire that the victims are freed from Dracula’s influence, as no one is safe from his corruption as long as the source still exists. Housman’s reworking of finality in the corruption of the blood is ultimately what makes The Were-Wolf so unique. In Housman’s story, it is Christian’s pure blood that frees his brother Sweyn from White Fell’s corruption, indicating that pure blood can be just as powerful as, if not more so than, corrupted blood. Housman is exceptional in this portrayal of blood from a positive perspective.

Interestingly, prior to Christian’s death, Housman only uses the word “blood” three times. Its infrequency makes Clemence Housman’s story unique when compared to other gothic narratives. Housman’s distinctive depiction of blood can be seen most clearly when contrasted to lycanthropy literature published prior to The Were-Wolf, such as Frederick Marryat’s The White Wolf of the Hartz Mountains (1839) and Sir Gilbert Campbell’s The White Wolf of Kostopchin (1889). These works featured a female werewolf, associated with the colour white, who attacks and consumes her victims in a traditionally graphic way. In her article “Upright Citizens on All Fours: Nineteenth-Century Identity and the Image of the Werewolf” Chantal Bourgault Du Coudray states that by the time Clemence Housman had published The Were-Wolf the character of the femme fatale cannibal woman had begun to border on cliché (6). Housman challenged this cliché with her depiction of the contrast between blood consumption and sacrifice.

Figure 1. Everard Hopkins's illustration of White Fell and Rol for Atalanta (1890)

Figure 1. Everard Hopkins's illustration of White Fell and Rol for Atalanta (1890)

In The Book of Were-Wolves Sabine Baring-Gould explores the idea of women losing their maternal instinct, as he claims that the obsessions with the consumption of blood can appear during pregnancy, specifically noting that the “appetite becomes diseased” (80). Housman’s character of White Fell demonstrates such a diseased appetite in her treatment of her victims. When exposed to Rol’s open wound she pulls him to her chest in a firm hold. She does this not to show him compassion or concern, but instead to hide her “awful glee” at the sight of his wound and dressing (Housman 27). In addition, White Fell seems to select her prey by reacting to those who engage in oral contact with her in the form of kissing. She returns the gesture, as if tasting her future prey, as only those whom she kisses become the focus of her attacks. This is proclaimed by Christian after the deaths of Rol and Trella, when he asserts his awareness of his brother as the next target (Housman 86). White Fell’s lack of maternal instinct and predatory kisses suggest the “diseased appetite” for flesh and blood that is customary in lycanthropic literature.

Where Housman differs from the traditional gothic narrative concerning the werewolves’ “diseased appetites” is in her lack of description of White Fell’s violent acts of consumption. Housman only hints at what horrors have occurred, such as in the case of Rol’s demise, where it is speculated that “a wild beast had devoured him” (Housman 48). Traditionally, lycanthropy narratives sensationalize the acts of violent slaughter and corrupt consumption. In contrast, the fates of Rol and Trella depend on the reader’s knowledge of lycanthropy folklore in order to conclude that they have become victims of a werewolf.

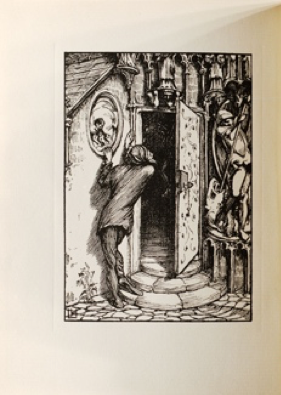

Housman’s use of blood challenges the traditional paradigm of lycanthropy narratives as it does not accent horrific cruelty. Instead, blood stands for salvation through Christian's sacrifice of himself for others. Housman’s use of blood as a key narrative device is foreshadowed early in the frontispiece of the Bodley Head’s publication of The Were-Wolf. The image “Holy Water” depicts the character of Christian haloed by the image of a mother pelican.

Figure 2. Laurence Housman, "Holy Water,” frontispiece to The Were-Wolf (1896)

Figure 2. Laurence Housman, "Holy Water,” frontispiece to The Were-Wolf (1896)

This image can be considered essential to the interpretation of blood in the narrative. Illustrator Laurence Housman’s close collaboration with his sister suggests the symbolic connection was intentional. The symbol of the mother pelican plucking at her breast until she draws blood to feed her young, which symbolizes the sacrifice of Jesus Christ and religious purity, often appears in church architecture and decoration.

Figure 3. Pelicans symbolizing Christ's love for the Church, from Chester Cathedral choir stalls, 1380. Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 3. Pelicans symbolizing Christ's love for the Church, from Chester Cathedral choir stalls, 1380. Wikimedia Commons.

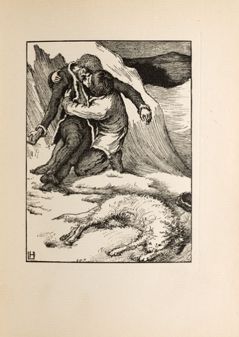

This maternal image of self-sacrifice challenges the negative connotations of blood consumption and its traditional representation within the lycanthropy genre. Later in the narrative Christian’s blood effectively becomes holy water itself, acting as the tool of White Fell’s destruction. The final plate highlights that White Fell transforms to a werewolf at the moment that Christian’s pure blood falls upon her (fig 4).

Figure 4. "Swyen's Finding." Illustration by Laurence Housman showing Sweyn holding his dead brother Christian, with the transformed White Fell a corpse at their feet (1896)

Figure 4. "Swyen's Finding." Illustration by Laurence Housman showing Sweyn holding his dead brother Christian, with the transformed White Fell a corpse at their feet (1896)

At the end of the story Housman reworks blood as a symbol of transformation and redemption (Hodges 60). White Fell’s volatile reaction to Christian’s blood can be linked to the transformation brought about by Christ’s sacrifice, as symbolized in baptism. In The Book of Were-Wolves Baring-Gould links the origin of werewolf mythos to Norse berserker traditions, stating that the only way for a true berserker, and therefore werewolf, to be cleansed of their animalistic elements is through the act of baptism (Baring-Gould 23). In the climax of The Were-Wolf, where Christian dies and his blood spills on White Fell’s body, he effectively baptizes her. Since White Fell is originally a wolf and has no human form to which she can return she is killed instead of being “saved.” This is in alignment with Baring-Gould’s multiple mentions that once blood has been shed by a lycanthropic creature it reverts back to its original form.

Clemence Housman seems to be aware of the traditional folklore, as she utilizes most of the established mythos concerning blood, holy water, and transformation in The Were-Wolf. She also challenges it and gives these themes a unique representation by making Christian’s blood a source of purification and cleansing instead of linking it to the horrific representation usually attributed to lycanthropic and vampiric fiction in the period.

Michael Seravalle, Ryerson University, 2018

Citation: Seravalle, Michael. “Blood in The Were-Wolf.” Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Michael Seravalle, et al., COVE Editions, 2018. https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/blood-were-wolf

Works Cited

Baring-Gould, Sabine. The Book of Were-Wolves. Smith, Elder & Co., 1865.

Du Coudray, Chantal Bourgault. “Upright Citizens on All Fours: Nineteenth-Century Identity and the Image of the Werewolf.” Nineteenth-Century Contexts, vol. 24, no. 1, 2002, pp. 1-16.

Hodges, Sheri. “The Motif of the Double in Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf.” Housman Society Journal vol. 17, 1991, pp. 57-66.

Housman, Clemence. The Were-Wolf. Illustrated by Everard Hopkins. Atalanta, vol 4, no. 39, Dec. 1890, pp. 132-156.

—. The Were-Wolf. Illustrated by Laurence Housman. John Lane at The Bodley Head, 1896.

Stoker, Bram. Dracula. Archibald Constable & Co., 1897.